Things were about to turn nasty?

For many of us, Timothy Dalton’s third Bond film is the most tantalising ‘what if?’ of the franchise. Targeted for a 1992 release, we all know it wasn’t to be. But what isn’t so well known is a TV drama that Dalton made at this time which gives us a glimpse of how a darker, queerer Bond 17 might have turned out had he stayed in the frame.

We already have a strong idea of what Dalton’s third film was shaping up to be like. Actually, that should be plural: ideas.

In his brilliantly-researched book, The Lost Adventures of James Bond, Mark Edlitz thrillingly investigates Bond 17’s gestation from a treatment to a screenplay. He also uncovers a treatment for what could have been a fourth Dalton film and examines an earlier treatment from 1985 which would have made Dalton’s first Bond film the character’s origin story, two decades before we eventually got to see Bond’s beginnings in 2006’s Casino Royale.

All four stories are very different. Despite Bond 17 containing overlapping ideas in both its treatment and screenplay iterations, Edlitz notes that what started life as “irreverent action-comedy” becomes a “stylish thriller” by the time it came to fleshed-out life as a 120 page script.

The question of tone is an intriguing one. Would Dalton’s third film have continued in a more serious vein of Licence To Kill, acquired a lighter touch or been something of the hybrid of the two like The Living Daylights?

We’ll never know of course. According to Phil Noble Jr, the version of GoldenEye written with Dalton in mind made Bond “a bit angrier” than the one we got with Brosnan. In contrast, the Bond 17 screenplay uncovered by Edlitz was written at around the same time and, based on Edlitz’s account of it, seems to be more playful.

In the early ‘90s, pretty much everything in the world of Bond was in flux. And because we never got to see Dalton’s Bond again we were denied the chance to nail down what ‘Dalton’s Bond’ was and wasn’t. In truth, that may have been a good thing. For everyone who loved the more ‘Fleming-esque’ approach taken in Licence To Kill (and Dalton himself was a vocal supporter of this direction) there were many others who decried this drier take on the character. It’s worth remembering this latter group were the vocal majority until relatively recently.

Personally, whatever the various treatments and screenplays reveal, I think a swing back to a more tongue-in-cheek adventure was inevitable, as happened following On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (with Diamonds Are Forever) and For Your Eyes Only (with Octopussy). The latter is especially notable because it featured the incumbent Bond playing the role differently. Some find this apparent inconsistency infuriating - I find it opens up possibilities: we’re all capable of change.

But what if the Bond producers doubled down on Dalton’s darker take? They have always said that the role is shaped around the actor and if Tim willed it, perhaps it could have been the case?

Regret is always an exercise in futility, and especially in the case of Dalton’s third film. There’s little point pining for a film that never existed beyond the treatment or screenplay stage. None of the approaches that we are aware of ever came to fruition. Even so, I find it impossible to stop myself from pining at least a bit and it’s fun to speculate. We just need to not lose sight of what others might like while we - inevitably - bring our personal taste to bear.

As I read Edlitz’s book (which covers many more ‘lost’ Bond projects besides potential Dalton adventures), I couldn’t help doing what we all do: cherry-picking the parts of the unproduced Bond projects which I personally liked and disregarding those I didn’t. For me (as I’m sure you won’t be surprised to hear by now - the name of this website being something of a clue), the queer elements stood out. And, if I’m honest, what I read did start making me pine a little for what might have been.

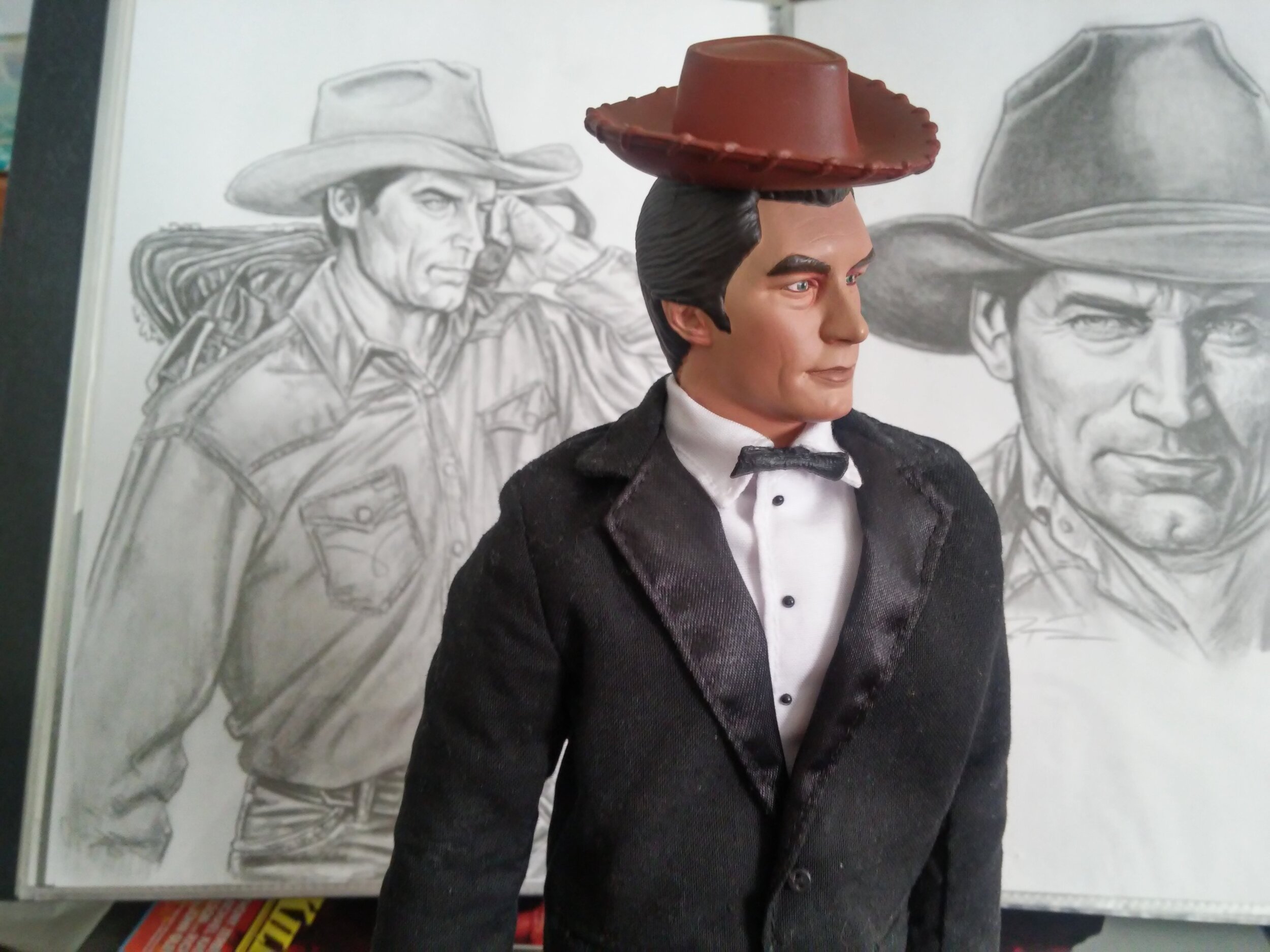

For a start, the Bond 17 screenplay features Bond infiltrating a rodeo disguised as a cowboy. Inside the book you will find two illustrations of this. Pat Carbajal’s art is always brilliant and here he depicts a top tier Brokeback fantasy that I’m sure would have infiltrated the dreams of many gay/bisexual men had it ever reached the screen.

There’s also a girl who not only has considerable agency but bluntly calls out Bond for his “macho” posturing (not surprising after that doth-protest-too-much cowboy get up). In the finale, when he’s sulking for partly failing the mission at the final hurdle, she tells him “being vulnerable makes you sexy”.

Most notable is a gay male ally called Jennings, whose skinheaded appearance subverts sissy stereotypes. Bond blushes when Jennings flirts with him, but remains gracious. No gay panic here!

Dalton himself is not averse to ‘playing queer’ on film, which remains a real fear for straight actors to this day. Right at the beginning of his career, he played the object of Anthony Hopkins’ affections in The Lion In Winter, the 1968 film from queer director Anthony Harvey.

There was a very real possibility then, that Dalton’s third film could have featured positive queer representation. Vitally, Bond 17’s Jennings does not end up dead, putting him several miles ahead of the majority of gay representations on screen, especially at the time. And as Edlitz notes, it’s more traditional for gay and bisexual characters in Bond to be villains so “introducing an openly gay hero into the franchise in the early nineteen-nineties would have been progressive”.

I swear my nerves are showing

CUT TO: 1990s

INT. A SUBURBAN LIVING ROOM - NIGHT

SUPERIMPOSE: “November, 1992”

A ten year old boy, DAVID, watches the TV, transfixed, surrounded by his family.

Merely weeks after I saw Timothy Dalton for the first time as Bond (in the UK TV premiere of The Living Daylights), I saw him again. But this time there was something different about him - something that both fascinated and terrified me.

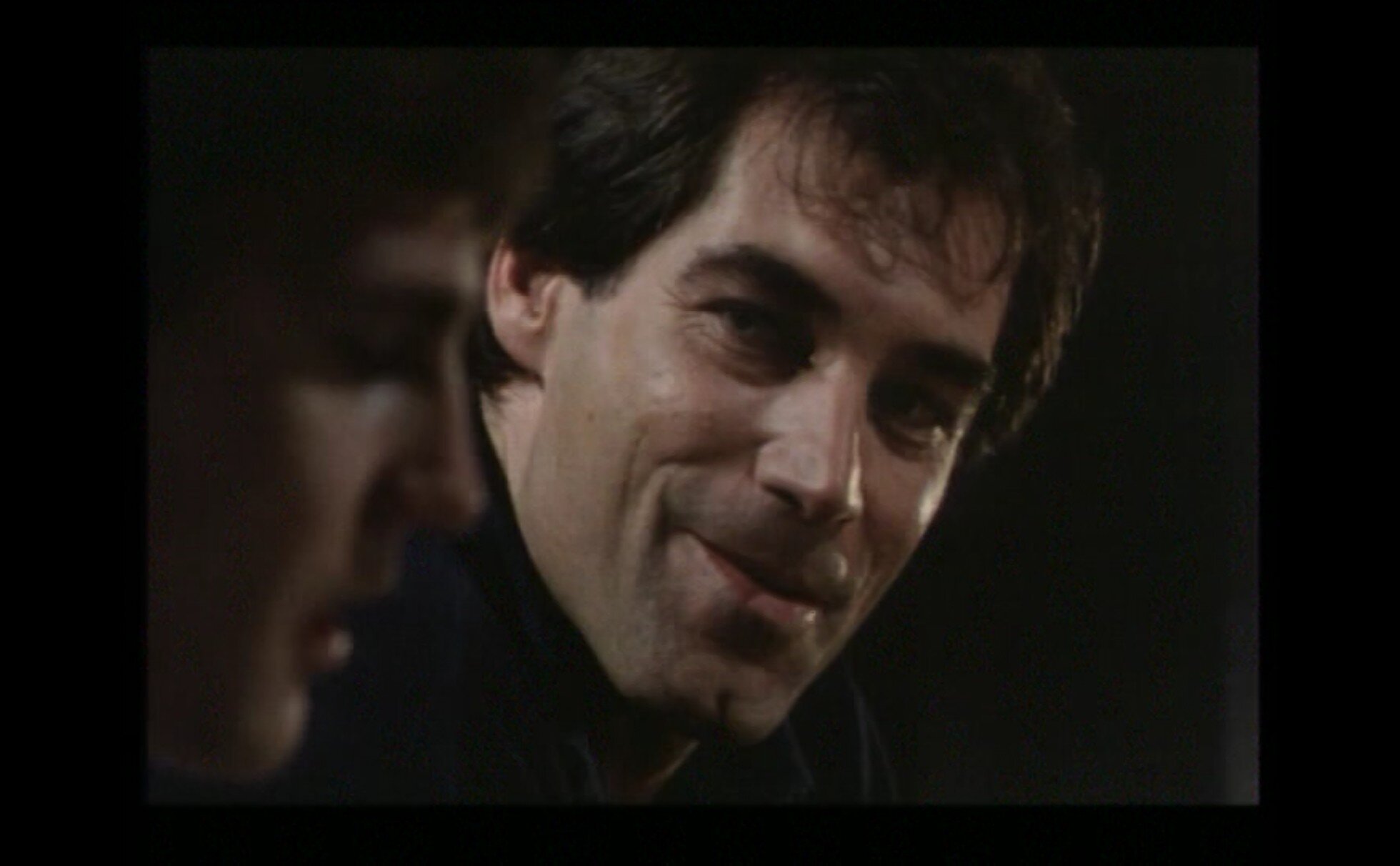

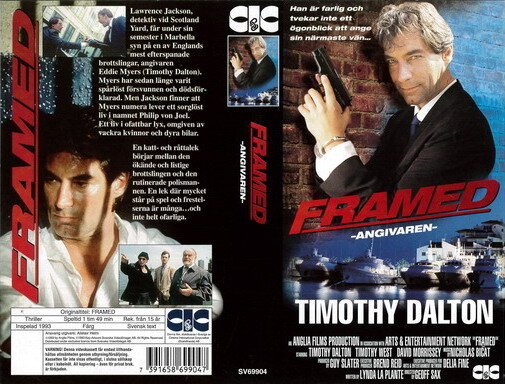

Lynda La Plante has said that she had Dalton in mind for the role of Eddie Myers, a real-life criminal who had escaped justice, when she was writing Framed.

I would like to think that by ten years old I could differentiate between a character and an actor, but I couldn’t help drawing comparisons with Dalton’s portrayal of Bond when I watched Framed for the first time. He may have looked like the same man in The Living Daylights (a carbon copy, right down to his clothing, in many scenes) but Dalton’s behaviour as this new character made Bond look positively squeaky-clean by comparison. Even so, like Bond, there was something undeniably charismatic about his character. There was also something undeniably queer about him, especially as seen through the eyes of the series’ other main male character, played by Dalton’s co-star David Morrissey. And also, as it happens, seen through the eyes of ten year old me. I watched Framed nervously, as I did anything which I knew, instinctively, to be gay. I felt my family might look away from the screen and see what was on there reflecting upon me. That didn’t mean I found it any less compelling...

Framed centres around the curious relationship between two men. Jackson (Morrissey) is “an ambitious young police officer, saddled with the responsibilities of a wife and children” (to quote the back of the DVD case). Myers (Dalton) is an escaped supergrass, a criminal turned informer, living it up in Spain. Jackson encounters Myers while on holiday with his family and an obsession begins. The exquisite tension of the series derives from us never really knowing either man’s true motivation. Ten year old me thought he had it worked out though: they were clearly in love with each other.

It’s difficult to overstate how much Framed burned itself into my memory in 1992 and the way it has held sway over my imagination ever since. As formative influences go, I place it alongside reading Thunderball aged eight and watching Diamonds Are Forever for the first time at around the same age. Unlike those two Bond adventures however, I had not revisited Framed as an adult - that was, until very recently.

In the 28 years that had passed since I first saw Framed, I had replayed particular scenes in my mind countless times. I had also replayed hundreds of times the song that appears on the soundtrack several times throughout the series; The Great Pretender by The Platters is always appearing on the playlists Spotify creates for me (thanks, algorithm). But I had purposely avoided rewatching the series itself.

The films and TV we consume as kids can often be disappointing when we revisit them as adults. Nostalgia plays a huge role here - the associations we have of a particular time, place or person we watched it with - but so does memory. Things we watch when young, and maybe don’t fully understand, we piece together in our memories, plugging the gaps with things we do comprehend. I have lost count of the number of films I’ve adored at first sight, not watched for decades and then found to be severely lacking upon rewatching them.

I was therefore hugely relieved when I bought the DVD and discovered it has only improved with age. And my ten year old reading of this being a straightforward love story between two men was not as reductive as I feared it might have been.

Not only is Framed a riveting tale in its own right with nuanced performances and nail-biting tension, but I also believe it gives us a strong flavour of what Bond 17 could have been like with Dalton as its lead.

You know I’m going straight for your heart

The following section goes into some of the detail of Framed as it relates to Dalton’s performance specificially. I have avoided giving away any of the significant plot developments after the first episode, but if you want to enjoy Framed for yourself without spoilers, you might want to skip ahead to the next section.

It’s currently not available on streaming services although - at the time of writing - someone has uploaded all four episodes to YouTube.

For an actor eager to avoid typecasting, the mixed blessing if not the outright curse of his Bond predecessors, Dalton’s decision to take on the role of fugitive criminal (and possible murderer) Eddie Myers must have been a no-brainer. But considering that Licence To Kill featured Bond very much on-the-run, having abruptly resigned from MI6, it perhaps isn’t the acting stretch it might at first appear to be. Licence To Kill’s portentous tag-line was ‘His dark side is a dangerous place to be’ and Eddie Myers could be seen as an even darker continuation of Dalton’s Bond persona: a kind of ‘what if Bond went very wrong?’.

When we first encounter Myers, it’s from afar. He’s frolicking around on a speedboat with a couple of women. So far, so very 007. Stuck on the nearby beach is Jackson, the police officer with whom we’re immediately invited to identify with. If the wife character hadn't been fully fleshed out in later scenes, we might even accuse this setup of being unfairly misogynistic. Certainly, the aim is to present the Jackson’s wife and two kids as ‘baggage’. Jackson is very much “saddled” (as the DVD cover has it) with family, a picture of heteronormative misery. He only has eyes for Myers. Is he more interested in the man or the mission?

Some of these early scenes could be taken shot for shot from Bond movies. One sequence has Dalton behind the wheel of a flashy car with two girls in the passenger seats, echoing similar imagery in The Living Daylights when he’s rescued/kidnapped by Felix Leiter’s glamorous assistants. A later scene, where Jackson steals a Champagne glass, in the hope he can confirm Myers’ identity by capturing a fingerprint, takes place at an art auction crammed with a cast of extras that could merrily be transported to any party scene in a Bond film.

If we had to pigeonhole Framed into a genre, ‘stylish thriller’ (the same one Edlitz uses for the Bond 17 screenplay) is a more accurate description than ‘crime drama’, which often carries connotations of the kitchen sink. For a British TV drama from the early 1990s, Framed is incredibly ambitious, with extensive on-location filming, both at home and abroad. Framed’s director, Geoffrey Sax, would later go on to bring similar gloss to Stormbreaker, adapting Anthony Horowitz’s first Alex Rider novel, which itself draws heavily on Bond.

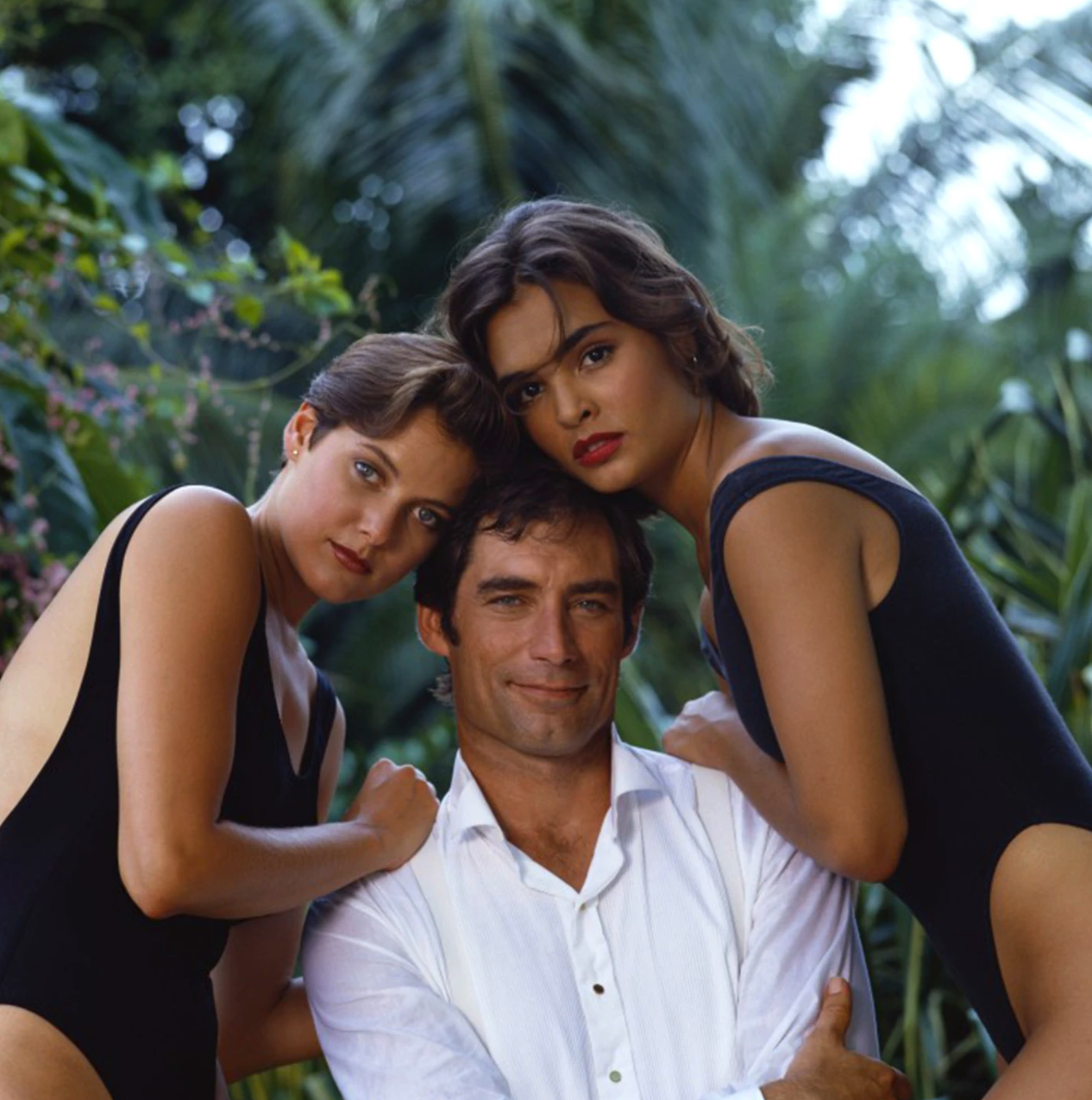

Lifestyle aspirations are baked into the very DNA of Bond. The notion that ‘men want to be him’ could equally be applied to the Myers character as played by Dalton. It’s strongly suggested that Jackson love love affair with Myers is rooted in his lifestyle - at least to begin with. Young police officer Jackson can just about afford a family package holiday to Marbella. While snobs might have turned their nose up at the ‘sun, sea and sangria’, this was quite aspirational in the early 90s (certainly it would have been for my family). But Jackson has nothing on millionaire Myers with his cars, yacht, speedboat and mansion with gigantic pool. The lifestyle goes well beyond material goods; it becomes clear early on that Myers is not heteronormatively constrained in the same way that Jackson is, with wife and kids in tow. Heteronormativity being the idea that the only normal and natural relationship is between one man and one woman, Myers subverts this by being in a throuple with two girls, played by Penelope Cruz and Rowena King, and it’s implied the two of them may be romantically involved when he’s not around.

It’s intriguing that the publicity photos for Licence To Kill show Dalton flanked on either side by the principal girls. It’s hardly unheard of for Bond to be flanked by women (Dr. No’s poster featured four of them, lined up in a row), but the Licence To Kill promotional shots seem to suggest that the women are more than passing fancies that he will work his way through, loving and leaving them, one by one. It’s a convention that flourished in the Brosnan and Craig eras, which sometimes dispense with Bond entirely, showing just the women in romantic poses. Framed does the same, with Cruz and King posed as partners, although less provocatively that Carey Lowell and Talisa Soto did for Licence To Kill.

These are images intended for a straight male gaze - that doesn’t mean that others (gay women, for instance) can’t find them appealing. It’s worth observing the double-standard here: just imagine if Bond and his male villains were posed as provocatively? (Trust me on this, there’s an audience; I know I am not alone in having imagined it!)

Once Myers has been extradited back to the UK, it quickly becomes clear that Jackson has been seduced by the criminal’s lifestyle - as have we, and we start to miss it immediately. To underscore the contrast with sun-kissed Spain, a clever dissolve takes from a pleasant fountain to the rain pouring down the windscreen of the police car containing Dalton. Welcome to Britain! Dalton grimaces as he catches sight of billboards advertising holidays to the sort of sunny place he’s just come from. This clever, economical sequence recalled to my mind the transition back to precipitous London in Quantum of Solace, but this is devoid of even a hint of glamour. It plants the seed of the idea that even a straight-as-an-arrow police officer might do anything to advance his lot in life, even go bent.

It starts to dawn on us (but not Jackson) that Myers’ plan was to seduce Jackson all along - perhaps in more ways than one. Myers agrees to return to the UK on the condition that Jackson stays with him and becomes, essentially, his handler. As a fellow officer tells Jackson, with more than a hint of homophobia, "He wants you to sit and hold his hand".

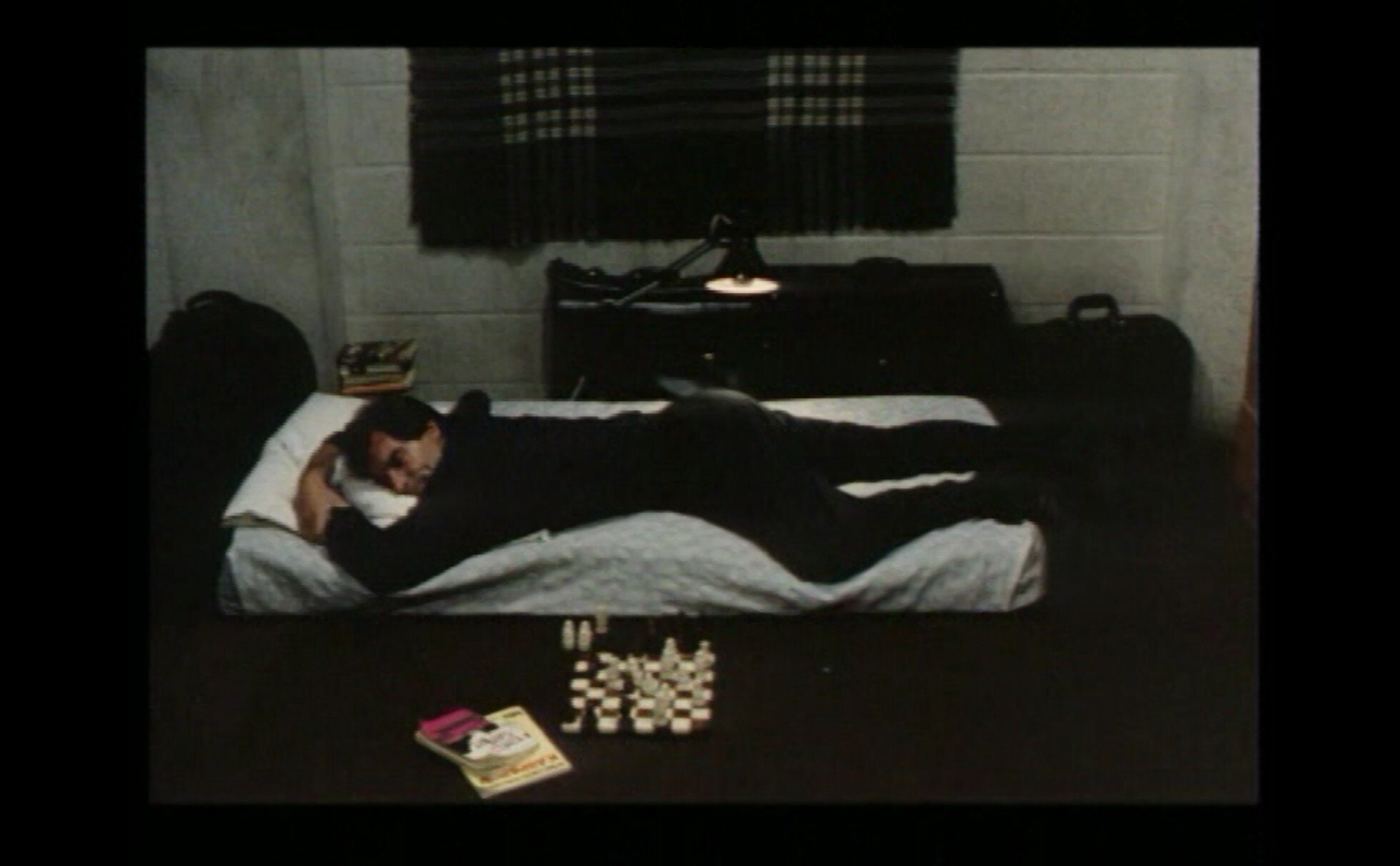

Things escalate quickly and Jackson ends up doing a lot more than holding Myers’ hand. Both men move in together, albeit for a somewhat contrived reason: once Myers starts to inform on his former gang, his life is at risk. The solution is to have Myers and Jackson holed up together in an underground police safehouse. Almost the whole of Framed’s second episode is concerned with the two men finding a way to live alongside each other by approximating heteronormative conventions - and subverting them.

Dalton is at his most Machiavellian here, taking his performance from Licence to Kill to the next level. As Bond, he had to become an arch manipulator to worm his way into Sanchez’s confidence and destroy his organisation from the inside. Like in Licence To Kill, the villain lends the hero his clothes, except this time Dalton is the villain. After noticing that Jackson has only packed an overnight bag and is having to wash out his clothing, Myers loans him his shirt. He also has him try on his jacket after noticing Jackson admiring it. By the time Myers is offering Jackson his underwear (which, he explains with relish, he has handmade in Paris) it is clear that the police officer is ensnared. When Jackson asks Myers to close the door it’s not clear why. Does he want privacy, just the two of them?

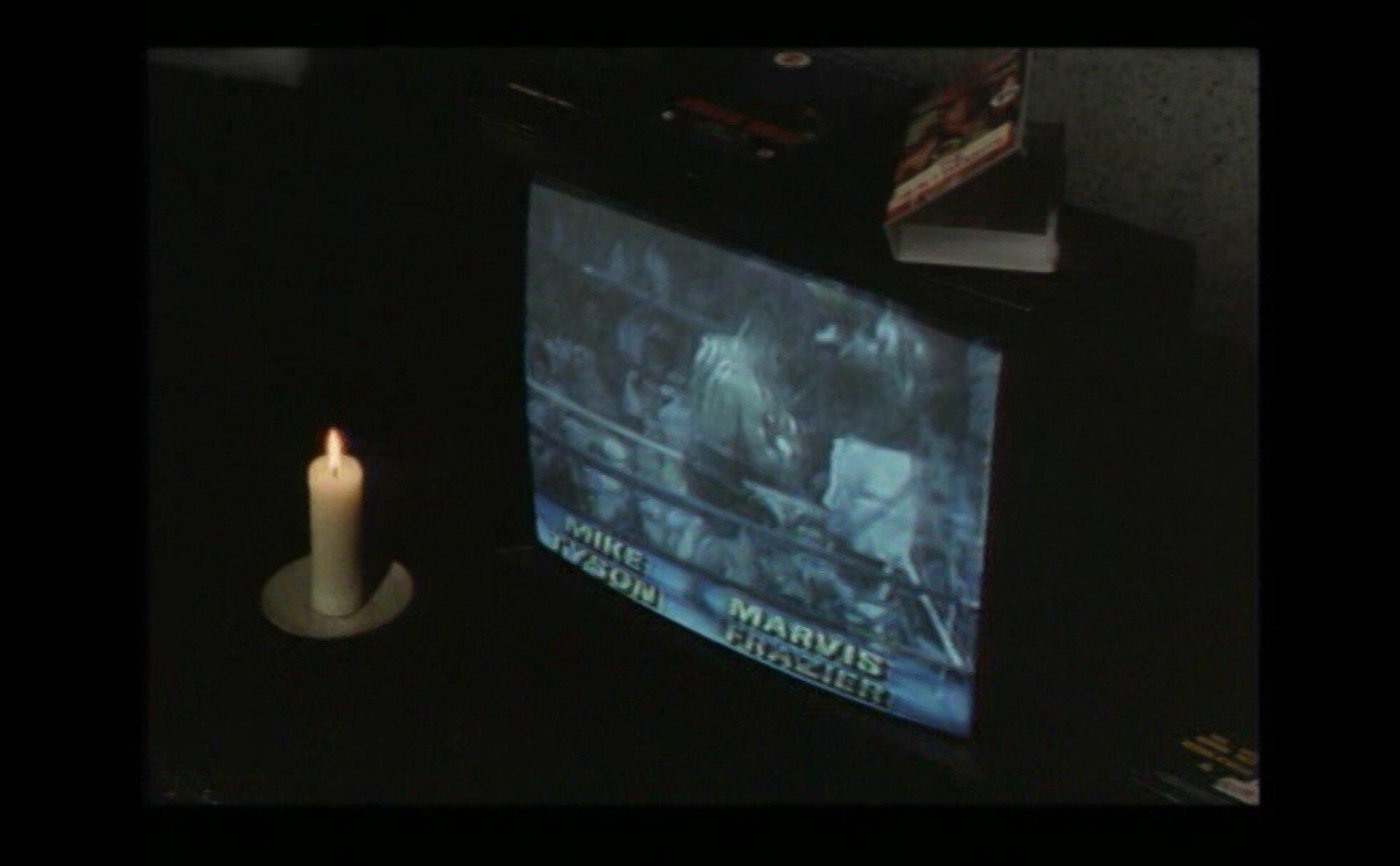

Pretty rapidly, Jackson is allowing Myers not just to dress him but also to educate him on improving his diet and fitness. They share meals together, with Myers doing the cooking, giving him the stereotypically passive, wifely role. He’s especially fussy about food, just like Bond, even having a hissy fit when the police supply English rather than French mustard, meaning he cannot make the salad dressing he wanted. Is Myers really this fussy or is he just playing at being the ‘woman’ of the relationship. So much is unspoken in these scenes. When Myers suggests Jackson and he sit down together to watch boxing on TV, Dalton makes it clear that Myers is not really interested in what’s going on in the ring: he’s faking interest in a masculine pursuit to alleviate any feeling that Jackson might be having that what they are doing is queer.

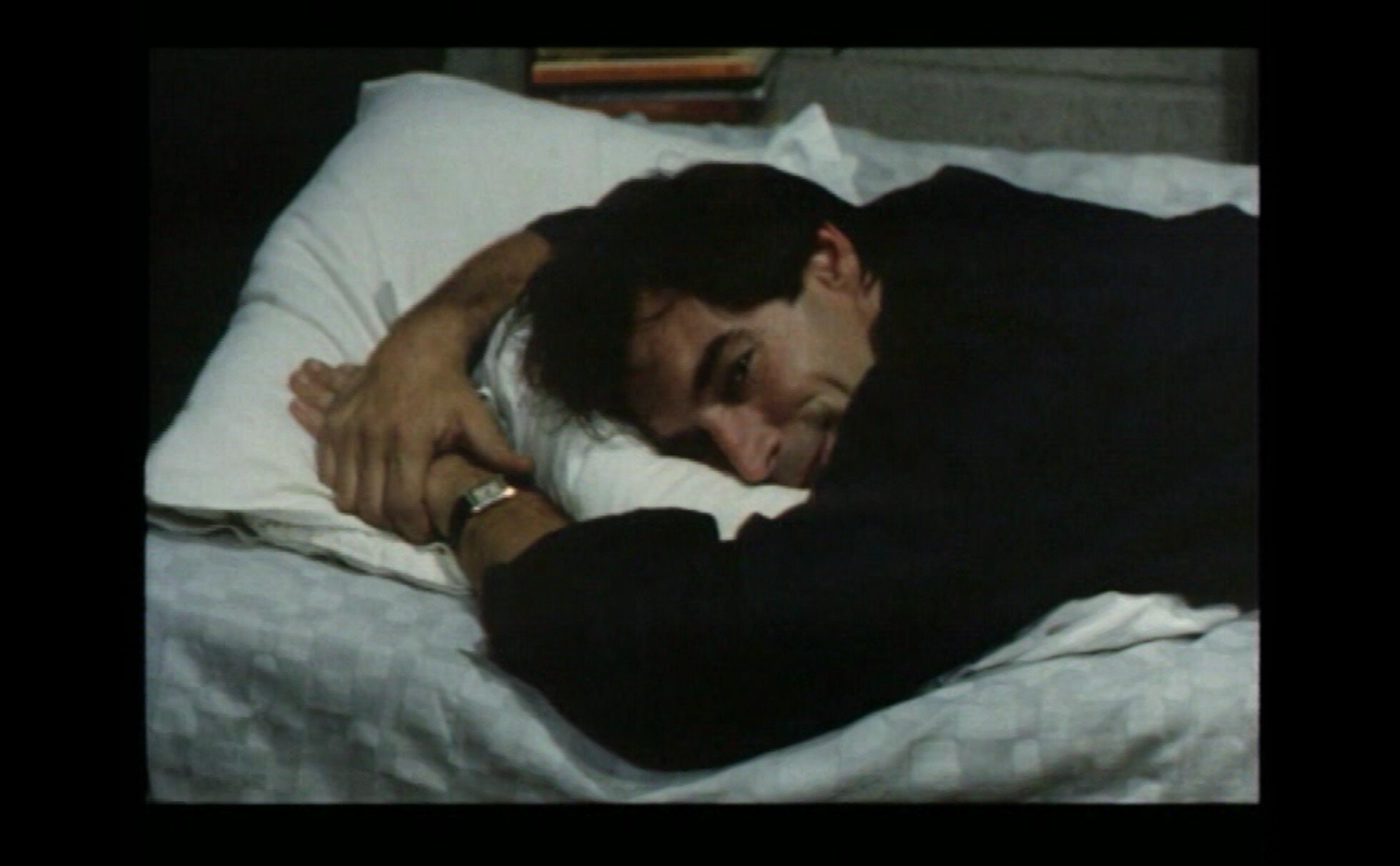

The queerness is heightened by these scenes being cross-cut with Jackson’s wife getting closer to another male police officer, ostensibly there to take care of her while her husband is on his secret assignment. We are told repeatedly that Jackson is refusing to see his wife. Myers even asks him about it. When Jackson do eventually return home, he launches into a tirade about his wife’s taste in magazines and furniture. He can’t wait to get back to Myers. When he does, the two men keep getting physically closer and closer, ending up lying on the floor together, like a married couple ‘at home’ with each other.

Myers increasingly brings sex into their conversation, culminating in him lying prostrate on the bed in front of Jackson, punctuating his speech by pressing himself into the mattress and sticking his rear into the air - a clear invitation to cross the line.

No wonder Jackson’s fellow officer asks: "You don't think he's bent do you?” Jackson’s response is wonderfully naive: "He had great looking women in Spain".

This seduction of Jackson is the real drama of Framed. The crime elements are often pushed to one side, the details dispensed with quickly or offscreen so we can focus on the chemistry between Dalton and Morrissey.

While it’s incredibly doubtful that a third Dalton film would have pushed boundaries to the extent of having Bond initiate sex with another man, it’s interesting that having an openly gay character who flirted with Bond was part of (one of) the plans. Who knows: maybe Dalton would have felt confident having Bond reciprocate his gay ally’s flirtations?

The great pretender

If Dalton had played Myers as merely a predatory, over-sexualised bisexual figure (a persistent stereotype), then I wouldn’t be recommending Framed so highly. I also doubt it would have lingered for nearly three decades in my memory. The acting and the writing are simply better than that.. While the sexual attraction between the two men is evident to me as an adult, it’s the possibility of there being something romantic as well which, in hindsight, chimed with ten year old me.

The second episode ends with a shocking act of violence which deeply upset me as a child. Not because of the nature of the violence (although it is quite bloody!), but because it threatens the burgeoning relationship between the two men. Strangely, when I rewatched Framed recently, I could barely remember anything that happened after the midway point. It was a long time since I had seen it though and this is certainly not a slight on the drama: episode 3 is a thrilling lead up to a brilliantly ambiguous finale which contains several more Bond echoes, including Dalton wielding a pistol and a car chase which recalls The Living Daylights, albeit with a Jaguar in place of an Aston Martin. The filmmakers are having great fun at playing with and darkening Dalton’s Bond image.

But it was the ‘love story’ build up of the first half which was secured in my memory. In hindsight, it’s obvious: for me, as a queer kid who knew he was different, I hungered to see myself represented. And if that representation took the form of a cop and a robber learning how to live - and possibly love - together, then I would take that.

Perhaps also the ending of the second episode is so lodged in my brain because it climaxes with a rousing rendition of Framed’s de facto theme tune. The song The Great Pretender, performed by early rock ‘n’ rollers The Platters, reappears throughout the drama. It’s first heard in the background at the art auction, perhaps suggesting it’s a track picked by Myers himself and therefore his motif. But it comes to the fore at the end of episode two, playing out contrapuntally against the violence.

The lyrics are not dissimilar from later Bond songs, especially those from the Craig-era, which emphasise angst, loneliness, identity crises and having to conceal, rather than reveal, your feelings:

Oh yes I'm the great pretender

Pretending I'm doing well

My need is such I pretend too much

I'm lonely but no one can tell

Oh yes I'm the great pretender

Adrift in a world of my own

I play the game but to my real shame

You've left me to dream all alone

Too real is this feeling of make believe

Too real when I feel what my heart can't conceal

Ooh ooh yes I'm the great pretender

Just laughing and gay like a clown

I seem to be what I'm not you see

I'm wearing my heart like a crown

Pretending that you're still around

Although it’s the jaunty 1955 original recording which appears in Framed, the song had been popularised in 1987 by Queen singer Freddie Mercury, a queer resonance I was unaware of at the time but one I suspect Lynda La Plante intended.

Lyrically unchanged, Freddie Mercury makes the most of every line he delivers, appropriating a song which was originally about a heterosexual man pining for his lost girl and turing it into a paean to the pain of the gay man’s experience. That’s how I always heard it anyway - at least after hearing it in the context of Framed.

Pretending, concealment, being adrift in the world and loneliness permeate every frame of Framed. They also infuse many Bond movies, especially both of Dalton’s.

Please don't bet that you'll ever escape me

A final parallel between Framed and Dalton’s possible third Bond film is rooted in the real-life Myers himself, who writer Lynda La Plante got to know very well. La Plante began work on Framed in summer 1989. Travelling on a forged passport, she tracked Myers down and made an arrangement with him: he would tell her his story if she agreed to live with him in his villa for two weeks. She would not be allowed to leave. No wonder the second episode of Framed, with the two characters locked up together, rings so true!

La Plante cited Myers’ vanity as the reason why he agreed to tell her his life story declaring him to be “the most egotistical man I’ve ever met in my entire life. As long as he was talking about himself and what he felt--about poetry, art, films--he’d talk.”

James Bond is no stranger to his ego either. In fact, most of Dalton’s signature roles are men with oversized egos, including the sneering villain (a Hollywood actor who is secretly a Nazi) of 1991’s Rocketeer, a role he took while waiting for Bond’s legal troubles to be resolved. So it’s beautifully ironic that Dalton himself is, according to those who have worked with him, humble, quite shy and unassuming. In a live TV special promoting Licence To Kill he is almost shaking with nerves at being interviewed until the host, Terry Wogan, gives him a glass of Champagne to calm his nerves. It’s a charming moment that shows any braggadocio and brutality he brings to his onscreen roles is purely professional.

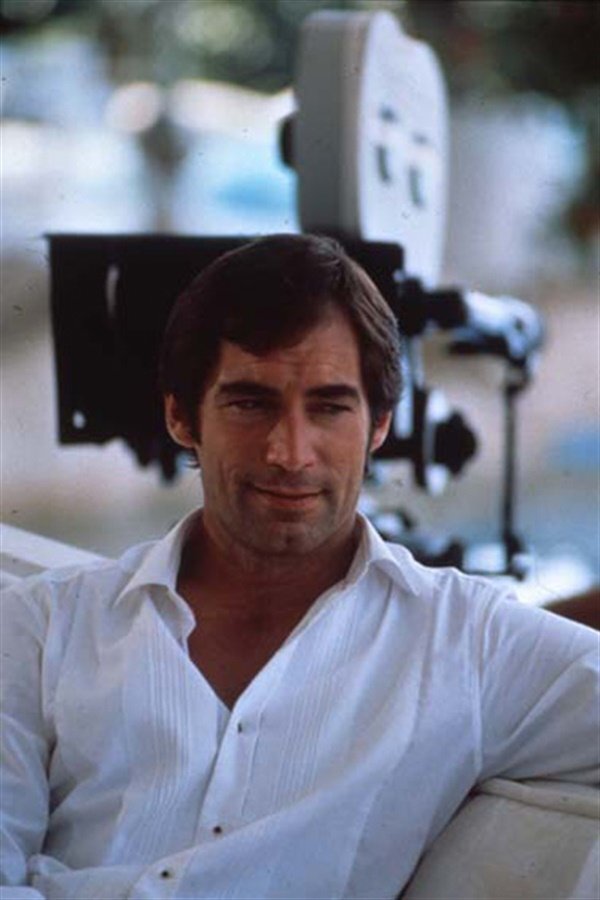

But his image - and let’s be honest, he’s an attractive man in anyone’s estimation - allows him to play characters who would be just as likely kiss you as kill you. And probably both. When he first takes aim at Kara through his sniper scope in The Living Daylights, we feel there’s a very real chance that he will go through with the mission as planned. With Roger Moore, George Lazenby and even Sean Connery there would be no doubt in our minds: there’s no way their Bonds would shoot a woman.

And Dalton plays insidiously sexy like no other Bond, capable of manipulating his way into anyone’s affections - female or male. He’s an actor who would not be out of place in the classic film noir period - a homme fatale, as it were. His two completed Bond films and Framed have that noirish trait in common; they’re very good-looking but they have a dark undercurrent.

And what of the ‘lost’ third film? With a dangerously attractive Dalton at its centre being eager to double-down on the darkness and a script which didn’t flinch away from authentic gay representation, it’s fun to imagine how things might have transpired.

Perhaps Dalton channelled some of his intentions for further developing his Bond into his portrayal of Eddie Myers. Perhaps not. What we know for certain though, courtesy of Lynda La Plante’s close observations of the real Myers, is that there was something of Dalton in - or rather on - Myers. Many people say (or keep to themselves) that they want to be James Bond. The real-life Eddie Myers took this rather literally, using some of his ill-gotten gains to make it a reality - of sorts. While staying with Myers, in 1989, around the time of Licence To Kill’s release, La Plante kept thinking he passed an uncanny resemblance to Timothy Dalton. She later learned he’d had plastic surgery make himself look more like the actor.

Save the darkness, let it never fade away

The similarities between Dalton’s two Bond films and the TV series he made at the time he could been shooting his third 007 adventure are more than just skin deep. Rewatching Framed after completing my queer re-views of The Living Daylights and Licence To Kill made it feel like a continuation of sorts. And yes, I’ll admit, as I watched Framed, the ‘what if?’ question kept popping into my head. But as I noted earlier, we shouldn’t have any regrets. I love the Brosnan films that came afterwards and I wouldn’t want to re-write history even if I could.

In recent interviews, including one in 2016, Dalton said that, had he done a third, he was interested in taking “the best of the two” he had done and consolidating them, perhaps suggesting that something tonally akin to the extant Bond 17 screenplay was on the cards. Or maybe Dalton viewed “the best” bits from Daylights and Kill as just the harder edged moments. Perhaps he would have taken it in the complete opposite direction; feeling more confident in the role, he might have taken a bit more time with the punchlines and delivered the quips with a lighter touch. His subsequent film and TV roles have shown him to be capable of as much light as shade, even when he’s playing outright villains.

And yet, for me at least, the shadow of his ‘dark side’ Bond will never fade. It looms over everything that has followed.

Like an ice cold, bone-dry Martini, Dalton’s Bond is not to everyone’s taste - but it’s something that deserves to be savoured. And just to double strain that metaphor: a commonly voice sentiment (one I happen to agree with with entirely) is that two Martinis are never enough but a third might be too much, especially with the measures James Bond demands from his bartenders. Similarly, having only two Dalton movies leaves us curiously unsatisifed and craving a third. But would a third have been too much, tainting what came before, a radical departure from the norm?

It’s a risk I can’t help feeling should have been taken.

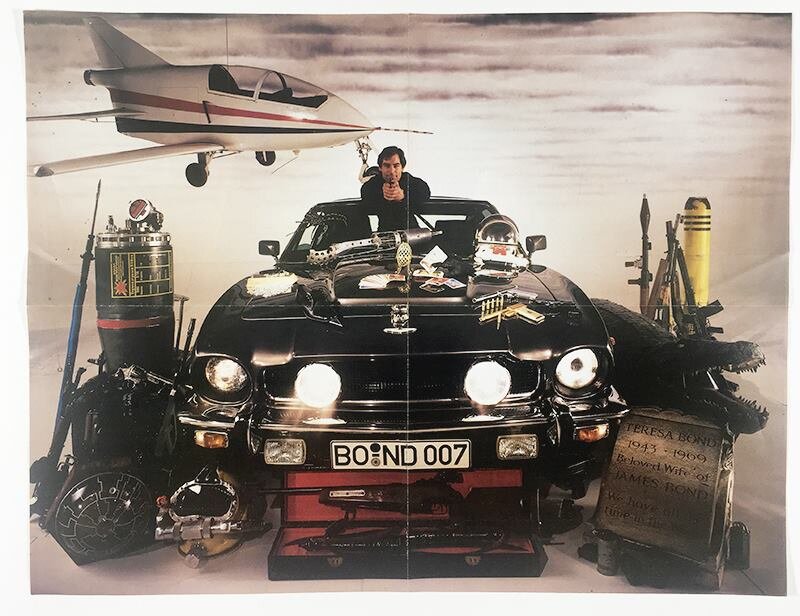

Thank you to everyone who has contributed directly (cited in the piece) or indirectly to this piece. Although the “Really, 007!” boys aren’t cited, their love for Daltz helped form some of my thoughts. Thank you to Pat Carbajal for sourcing for me the ‘smiling’ variant of this brilliant photograph which appeared as a double-page spread in the April 1987 issue of Life magazine. The non-smiling version is on Thunderballs, along with many other rarely seen shots of Tim, some of which I used to illustrate this article.

Pat also tracked down this DVD cover for Framed which shamelessly pastes Dalton’s head onto a model doing the Bond pose.

Note on different versions of Framed

Although it is structured around cliffhangers, Framed is best seen as a 200 minute-long movie. In fact, it was later re-edited into a film for the US market. This bowdlerised version is not well liked, at least by those who have seen the TV original. I have not seen it myself but I have read that they trim mostly from episodes one and two, perhaps because it contains the most blatantly homoerotic scenes, making it more palatable for a wide audience in the early 90s. Framed was remade as a film in 2002 starring Sam Neill as Myers and Rob Lowe as the Jackson character. I haven’t seen this either.

Images from Framed are copyright Anglia Films. Used for educational purposes.