Let’s put the codename theory on ice - permanently

Those who subscribe to the ‘codename theory’ - the idea that James Bond is not someone’s real name but an identity passed from one agent to another - can’t deal with the apparent lack of continuity in the character’s appearance and personality over several decades. But for queer people in particular, it gives the character yet another dimension we can relate to: the ability to change while also staying, fundamentally, the same.

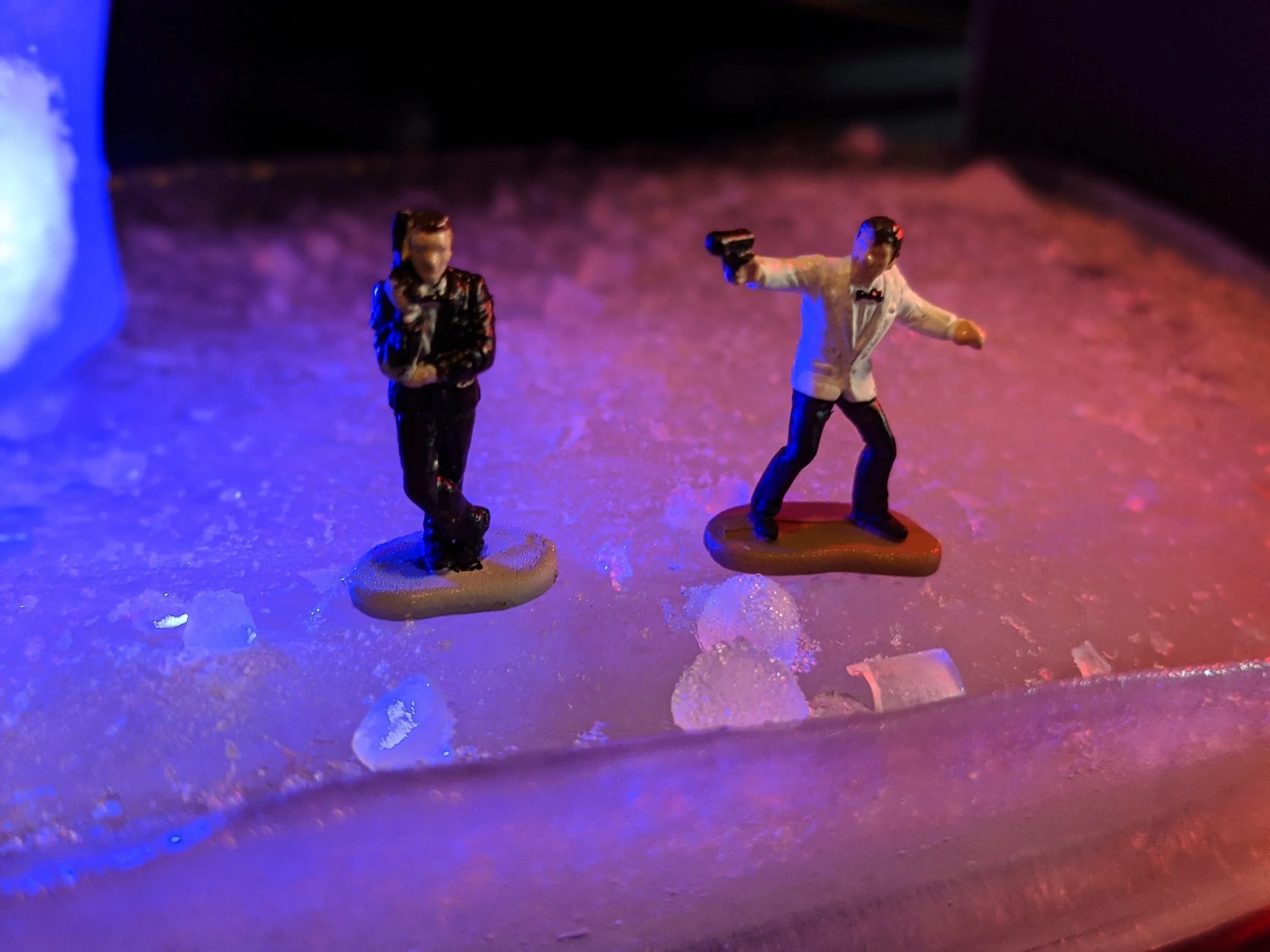

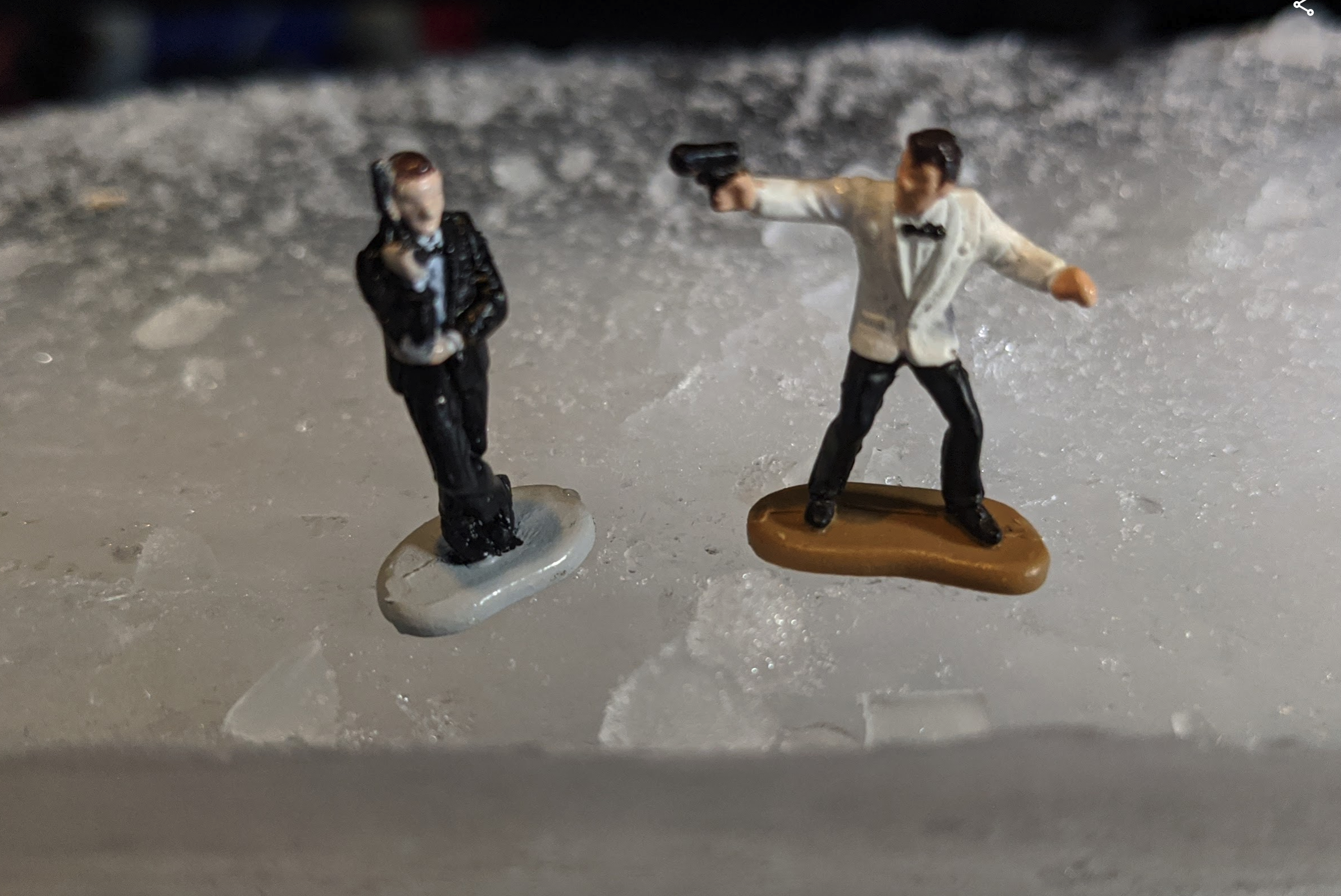

Imagine James Bond as an ice cube. Bear with me on this.

Back in the 1940s, an expert in change management called Kurt Lewin observed that for any organisation to change it had to go through three phases: unfreeze, change, refreeze. The first step is crucial: without first unfreezing (ice melting down into water) it cannot change and be refrozen. Like most brilliantly simple ideas, it’s applicable to a lot of situations. You can even apply it to people - especially queer people.

While literally melting people down sounds a bit sadistic, even for a Bond villain, we can certainly apply Lewin’s metaphor to Bond, especially because he has been played by six men. (I’m not counting Niven, Nelson, et al here because otherwise we’d be here all day but you can apply what follows to them as well if you have the time and inclination).

Whenever a new Bond actor takes on the character, the Bond ice cube has to be unfrozen. This enables the character to be remoulded to fit the actor - and the demands of the audience at the time.

It takes at least one film for an actor, and an audience, to figure out who a new Bond is. This is the unfreezing stage.

Because Lazenby only played the character once he remains somewhat unfrozen in most people’s minds (or just completely frozen, in some people’s unkind estimation of his acting style).

Moore took two films to establish himself: I always find it astonishing how cruel he can be at the beginning, especially in The Man With The Golden Gun, because these moments are so at odds with the five adventures that follow.

Brosnan is an odd one: he looks to be having the most fun as soon as film two (Tomorrow Never Dies) and then finds a well of GoldenEye-esque angst to draw on again. Courtesy of writers Purvis and Wade he’s unsure of his place in the world, something that carries on over to the Craig era. Perhaps because of this mutability, many criticise Brosnan for being basically an amalgam of Connery and Moore and never really his own man.

Not that it’s a competition, but Craig takes two films, like Moore. Or shall we say one and a half? I always see Quantum of Solace as an extended epilogue to Casino Royale after all.

While there’s something satisfying about a Bond actor hitting their stride, I always find the first film of a new Bond actor thrilling. It’s a chance to try out something new - within fairly tight character parameters at least.

What about Dalton then? I skipped over him on purpose because I find him the most interesting - from a unfreezing/freezing point of view.

There’s a reason ‘a third Dalton film’ tops the hypothetical wish list of many Bond fans. I suspect it’s because we never got to see him (in Lewin’s term) ‘refreeze’. The Living Daylights was an unfreezing - of sorts. It’s clear the screenplay was written without a specific actor in mind. Dalton races through the one liners which Moore and Connery would have savoured. Some of the more outre set pieces ended up on the cutting room (see the ‘magic carpet’ deleted scene on the DVD). There’s a cold callousness (Connery) balanced with a genuine humanity, particularly towards vulnerable women and male allies (Moore in his final three films). This hybrid approach unfreezes things to prepare us for the real change Dalton enacts in the next film.

For some, it’s a change too far.

Licence to Kill feels like a sudden knife or shot in the dark, coming seemingly out of nowhere. It was undeniably a provocation to the audience. How far do you want us to go with this ‘harder’ Bond? Although views were mixed on release, it’s the one Bond film more than any other which has undergone a (deserved, IMHO) reappraisal since its release.

The third film would have been Dalton’s refreezing moment. It would have been his Skyfall perhaps - a balancing out of the two adventures that preceded it.

What does this all have to do with queer people though?

Well, I would never be arrogant enough to even attempt to speak for everyone across the LGBTQ+ spectrum, but, as a gay man, I felt frozen for a very significant portion of my life. I felt like I was stuck in time. Like Austin Powers, frozen in 1967, I couldn’t move on. Except in my case, I was frozen around 1988, when I first realised I was probably gay. I didn’t start to unfreeze until around twenty years later, when I came out.

Like a lot of other gay people, it took a while for me to figure out my gay identity. I’d spent so long pretending to be straight but would I be more comfortable ‘camping it up’ a bit more? It wasn’t just that I didn’t see myself in a lot of gay stereotypes. I also had a fair amount of internalised homophobia which I had to work through. For instance, I didn’t take a great deal of pride in my appearance or agonise over what I ate because I thought those behaviours were too ‘gay’. Reading and watching James Bond actually helped here. Go down a list of stereotypical gay male traits and Bond checks most boxes. Whether he’s on the campier end of the spectrum (Roger) or the no-nonense end (Tim), many people point to Bond as the ‘ultimate man’. So, does that mean you can be gay and be the ultimate man? Well, yes. Cool!

In recent years, I’ve been even more open to ideas of what being a man actually entails, to the point that I would describe my gender as ‘muted’. I doubt I’ll be changing pronouns anytime soon but if I want to do something that’s stereotypically feminine (buy myself flowers, paint my nails, wear a women’s t-shirt with Bond girls on the front because they don’t do it in men’s sizes) then I no longer hold myself back.

I doubt that exploring my gender identity will be an unfreezing on the scale of opening up about my sexual orientation, but it’s an unfreezing of a kind. And it shows we can unfreeze, change and refreeze any number of times. Just like James Bond has - and will continue to do so. The only thing that needs to be frozen on a permanent basis (and forgotten) is the daft codename theory. It’s not a codename. You might like one version of Bond more than another but he’s the same person - just a bit different. Like the remixes of a favourite song maybe. You might love some versions and hate others.

I try not to get drawn into the ‘who is the best Bond?’ discussion. If someone brings it up, I actively try to steer conversation away from it.

But why do some people have such strong feelings about particular incarnations of Bond?

Queer academic Claire Birkenshaw tells me it might be because Bond is “like an ice core sample”. Another ice metaphor! She elaborates:

“Each layer of ice is able to reveal the conditions of the climate at the time of creation. Clearly the different climates captured in the ice samples will favour same types of flora and fauna better than others. So if each of the Bond actors has captured the climate of the era then each Bond actor will appeal or are relatable to people adapted for the climate at that time.”

So, if it’s like an ice core sample, there’s a time dimension then? It depends on the era you were raised and when you first got into Bond? Claire explains there is more to it than that:

“I think the different Bonds appeal to different people depending on how they were socialised. It’s quite possible there is an idealised version of Bond that exists in our minds. However, I think the idealised version shifts due to shifting cultural contexts and expectations. For example, we would now expect Bond not to be racist. We may allow some form of sexism which I think would have to be delivered ‘knowingly’ as a nod to a sexist past. Therefore, I think Bond depicts the cultural ideology of Britain. Bond has to be different forms of masculinity at the same time. So I would argue Bond has to be globally masculine as well.”

It takes courage to unfreeze; especially in front of an audience. In a Bond’s actor’s case, it’s a multinational audience of billions. But at least Sean, Roger, Tim and the rest didn’t know most of the audience personally. Queer people hope for the approval of those who know them best, or think they know them best.

There have been countless times since coming out myself where I have recognised that someone I know is struggling to make a significant life change. I’ve learned that the best thing I can do in these situations is provide them with warmth and affection in abundance. Only then will they have the courage to start unfreezing themselves.

There’s a lot of literature on the psychology of change which concludes the following: human beings are generally not in favour of it and will do anything to avoid it. It’s actually an evolutionary hangover that we have to work really hard to get past. Perhaps that’s why the Bond codename theory persists. Compared with the alternative, continuity can be comforting. The root of the word continuity is the Latin verb continere, meaning “to hold or keep together”. And even when Bond changes, we keep more of the Bond we already know than we lose.

Claire says this is something we can all relate to as we go through our lives:

“It’s quite possible that in melting and refreezing processes there are trapped air bubbles from the past which remind us of the journeys we have taken.”

[In the interests of full disclosure: my husband, who is also gay (as far as I am aware), subscribes to the codename theory, despite my attempts to win him around. He says continuity “makes things real” and will happily swallow any old codswallop rather than suspend disbelief. Whatever gets you through I suppose…]