Queer re-view: The Spy Who Loved Me

Queer pride and national pride rarely go hand in hand, so why does everybody love The Spy Who Loved Me? Bond has always embodied his nation and this film in particular – released in the Queen’s Silver Jubilee year – puts both Bond and Britain on top, in more ways than one. This cinematic male power fantasy should send running any viewers who don’t identify with ‘harder’ versions of masculinity, especially those which are intertwined with a hardline loyalty to country. But there’s something about Roger’s third entry that makes all of us, including queens and the Queen herself, just keep coming.

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

This article is also available as a podcast, wherever you get podcasts (direct link here).

Inspired by The Spy Who Loved Me’ by Herring and Haggis

Disclaimer for readers from Wales and Scotland: Where possible, I have tried to delineate between England and Britain, but Bond doesn’t help matters by using them interchangeably.

“But James, I need you.”

“So does England.”

“Bond, what the hell do you think you’re doing?”

“Keeping the British end up, sir.”

‘Lie back and think of England.’ – English proverb

The Spy Who Loved Me begins with Bond brushing off a Russian spy - choosing country over coitus - and ends with him keeping the British end up over another Russian spy. By bookending the film in this way, the filmmakers explicitly link nationalism and masculinity, two things which are “inherently intertwined” according to acclaimed lecturer of International Politics Koen Slootmaeckers. And the overridingly memorable image of the film - a Union Jack floating down the screen accompanied by Carly Simon telling us that Nobody Does It Better - quite literally unites Bond’s unparalleled male potency with that of his country.

But we should be careful when we talk of masculinity. It’s not just one thing: not homogenous or hegemonic. And it’s not exclusive to men of course. Women and non-binary people can have masculine qualities just as men can have feminine qualities. When we speak of masculinity, we should do so in the plural: masculinities. Like all the interesting parts of life, it’s a spectrum.

The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond

For me, The Spy Who Loved Me marks the point where Bond edges closest to the ‘harder’, even hypermasculine end of the spectrum, potentially making it harder for some queer viewers to identify with him. It can sometimes feel like overkill, especially when it comes to his sexual conquests, as if Bond is trying too hard to prove something, perhaps even putting on an brave show of it. This performative aspect though provides a way in for those of us who spent portions of our lives trying hard to conceal parts of ourselves. Furthermore, several stylistic choices - as we shall see - encourage us to not take Bond’s hypermasculinity seriously.

As a child who didn’t like sport or any typically ‘manly’ pursuits, Bond films did a lot of the heavy-lifting, providing me with an alternative model of masculinity. And in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when I was growing up, The Spy Who Loved Me seemed to be on TV more than any other Bond film. So frequently was it shown on ITV that I was convinced Jaws was in almost every Bond film, I was that used to seeing him take up most of the frame on our 21 inch screen.

I have vivid memories of watching the film over and over again. What I don’t have any memories of is feeling like I couldn’t connect with Bond, despite the gnawing sensation that there was at least one fundamental difference between me and the spy I loved…

Lie back and think of Russia

When we first meet Bond, he’s with a lady… (I’m already struggling to avoid slipping into the mindset and voice of Alan Partridge, for who this is The Greatest Film Of All Time and, for once, Alan is not far off the mark). Somewhat inevitably, the Log Cabin Girl played by Susie Vanner is revealed to be a Russian spy who has used her sexuality to snare Bond.

While Bond himself is no stranger to using his sexuality for the mission (“The things I do for England.”) it’s usually implied - when bedding Fiona Volpe or Helga Brandt for instance - that he’s not being entirely altruistic: he satisfies himself as well as the needs of his job. For all of the Log Cabin Girl’s protestations that she needs Bond, her demeanour shifts from fired-up to icy cold the moment Bond has closed the door behind him. Is this a suggestion that she was not taking much, if any, genuine pleasure from the encounter? To paraphrase a well-known British saying, was she lying back and thinking of Russia?

The first recorded use of a phrase along the lines of ‘lie back and think of England’ is in the 1912 journal of Lady Hillingdon, who wrote of her husband: "When I hear his steps outside my door I lie down on my bed, I open my legs and think of England." However, it was likely in use for a long time before 1912. It’s very revealing of a 19th Century mindset: a woman was expected to tolerate a man’s unwanted advances in order to populate the Empire. The phrase survived in popular usage well into 20th Century and is still widely understood today.

There is so much bound up in this phrase, not least of all the queasy-making non-consensual aspect and the mostly unquestioned view that a woman’s pleasure is subservient to a man’s. It also encodes the assumption that a woman should be lying down, passive, while the man should dominate, performing his nation-building purpose from above.

In The Spy Who Loved Me, there’s no argument that it’s Bond - representative of Britain - who is the one in control: he’s lying on top of the girl, establishing him as the active partner and therefore The Man. His ‘conquering’ of the Log Cabin Girl asserts Britain’s dominance over Russia.

The apparently modern associations with being on the bottom (submissive) or the top (dominant) are not new. Thus has it ever been, or at least for the last couple of thousand years. Positions come loaded with meanings. There have been – and still are – many cultures where even a man who is physically on top of another man is not seen as feminine and ‘gay’. Only the ‘passive’ participant gets labelled as such. Being the recipient of a penis automatically makes one ‘the woman’, it would appear, regardless of one’s actual gender identity.

According to some less enlightened corners of the internet, a man’s heterosexuality is compromised by pretty much any sexual position other than missionary, as illustrated by this 2021 reddit post which went viral, mostly because of how ridiculous it was:

It's somewhat pathetic really, isn’t it, this fear of being perceived as feminine? And who cares anyway? Well, it turns out, quite a few people do. It’s this fear of being thought of as less manly which has always been at the root of homophobia. And it’s been wielded as a weapon by manipulative national leaders for millennia.

Makes me feel sad for the rest

Most nations have, at one time or another, used homophobia as a tool. I’m not talking about just targeting individuals who are actually gay - although that does, of course, happen on a vast, terrible scale. I mean it in the sense that Koen Slootmaeckers does: homophobia is a technology utilised by nations to Other other nations. That’s a slightly confusing sentence, I know. But when we use ‘Other’ with a capital letter, we’re talking about a process whereby we position another group of people as ‘them’. This then increases the solidarity and national feeling of the people who are doing the Othering – ‘us’. Us versus them.

Suggesting – or outright stating - that your rivals are gay in order to belittle them and make yourself feel better is not limited to today’s school playgrounds. Greek nation-states did it. The Romans honed it. Throughout the 19th Century and well into the 20th Century, European nation-states whipped up nationalistic fervour by portraying the populace of other nations as more feminine and making their own people feel like the cock-of-the-walk. The British Empire justified colonisation of other nations by arguing that their men were effeminate and weak, particularly in India (as Edward Said has observed in his seminal text Orientalism). More recently, Russian nationalists have attempted to assert their country’s masculinity by portraying Western Europe as feminised and weak for its tolerance of homosexuality. That partly explains all those weird photos of Russian Premier Vladimir Putin expressing his masculinity. Because nothing says ‘grrrr’ like posing with your shirt off (although there are thousands of gay models on Instagram who do the exact same thing - I’m just saying!).

A fairly recent development is so-called ‘progressive’ countries Othering those which are less progressive because they have ‘backwards’ attitudes towards gay people (see, for instance, the langauge used by the Western media when reporting on the 2022 World Cup being held in Qatar). Jasbir Puar calls this ‘homonationalism’. It’s still using homophobia as a tool to Other. Both approaches are, in Slootmaeckers phrase, “two sides of the same coin”.

But at the time of The Spy Who Loved Me, it was the earlier approach which held sway. Looking down on anything feminine/gay went hand in hand with patriotism in Britain and most countries. I mean ‘hand in hand’ figuratively of course. Most men of a fiercely nationalistic bent wouldn’t be seen dead holding hands in public for fear someone might get the wrong idea.

Bond ‘77

The 1970s had been a transformative but often volatile decade for gay rights in many parts of the world, especially the UK and USA. As we see repeatedly through history, increased rights for any oppressed group leads to greater visibility which inevitably leads to backlash from sections of the population which feel like their preeminence is under threat.

Perhaps because of what was occurring in wider society, the filmmakers steer away from anything which might lead the audience to consider the possibility that Bond is anything but a warm-blooded heterosexual - albeit one with a pretty vanilla sexual outlook, certainly compared with what had come before with Connery, Lazenby and even the first two Moore movies.

In his 2014 study of how homophobia ebbs and flows over time, David Plummer proposed that nations are always in one of three different modes, all rooted in fear of men (and by extension, the nation) becoming more feminine.

1. Rejection (people refuse to accept any changes in gender roles);

2. Reaction (people are outspoken in their response to changing roles and revert to earlier, even more traditional gender norms);

3. Accommodation (a shift in gender roles is permitted).

It’s a misconception that societies progress along a straightforward linear pathway, from rejection to accommodation via reaction. Sometimes taking a step forward entails taking two steps back. Following the accommodations of the late 60s and early 70s (including changes in legislation), The Spy Who Loved Me was arguably produced in a reactionary period. To this end, Bond goes out of his way to restate his heterosexual credentials - metaphorically and geographically.

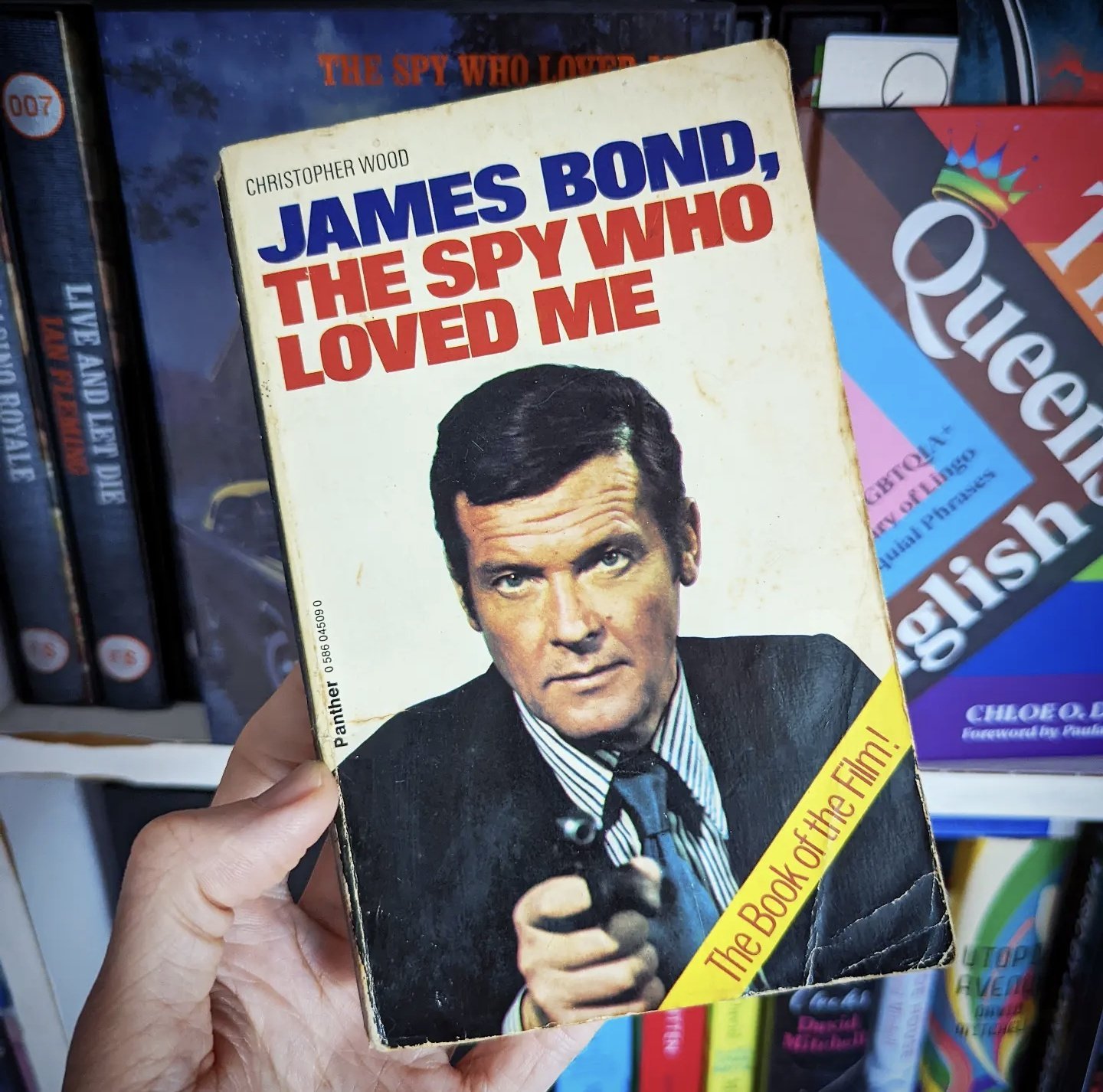

The scene where Bond reunites with his university friend, Sheikh Hosein, in the desert of Egypt is a salient example. It’s a delightful scene but it’s entirely superfluous to the plot. Interestingly, Christopher Wood did not include it in the novelisation of his own screenplay. The only purpose of the scene is to give Bond another treasure to delve into. A less heteronormative possibility that surely crossed the mind of Christopher Wood was to have Bond acquainted with more than one treasure. After all, the tent is full of them. In a comparable situation, Connery had slept with two girls simultaneously in From Russia With Love. And Lazenby wasn’t so much sleeping as spinning plates while disguised as Hilary Bray in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Even Moore in his previous film shared a bed with Andrea Anders while Mary Goodnight was stuck in the closet in the same room.

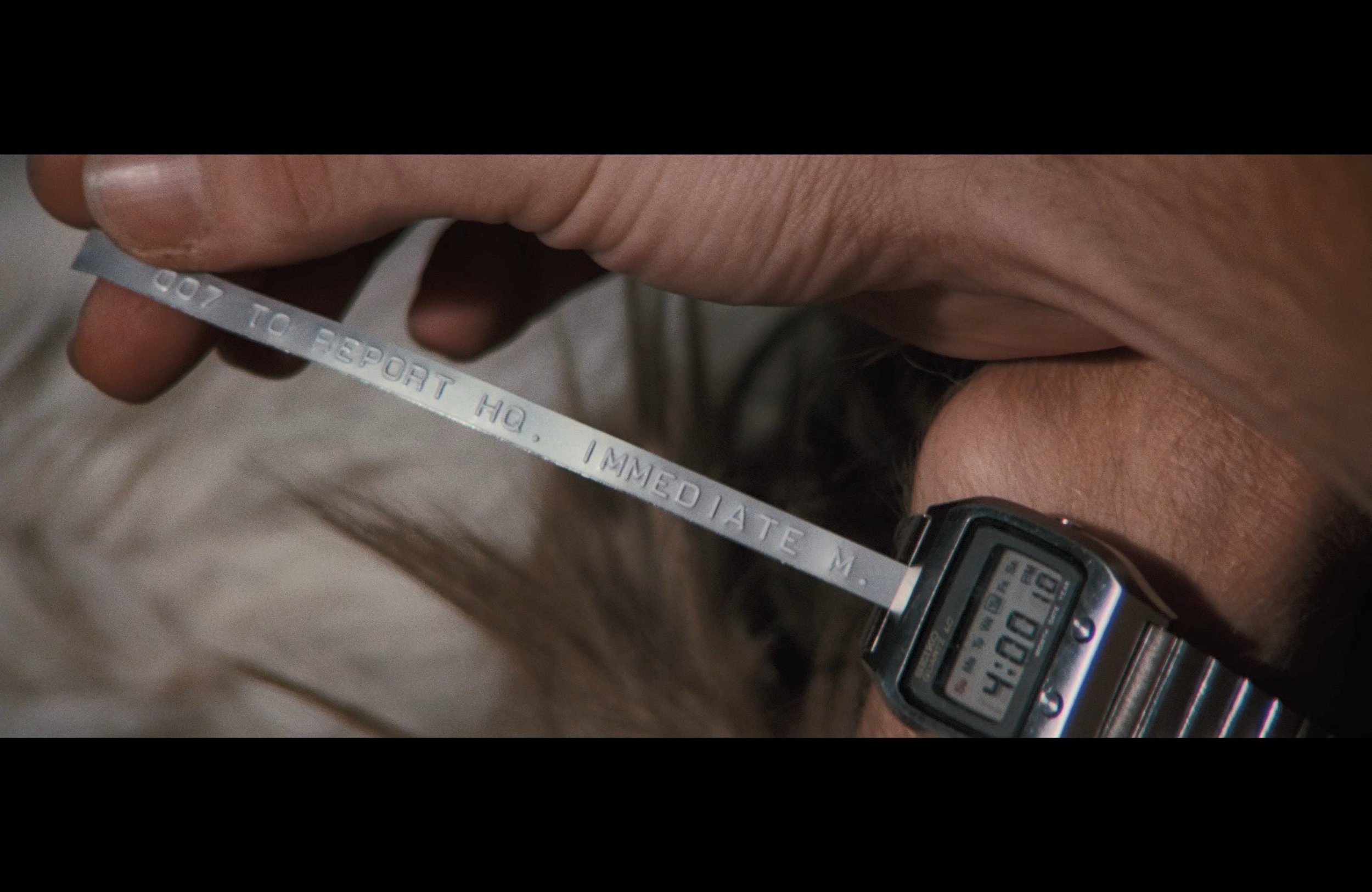

The Spy Who Loved Me, though, is strictly heteronormative (non-monogamy aside): one man and one woman. Penis-in-vagina intercourse between two people is the only option. There are relatively few references to other kinds of sex act, even in Bond’s witticisms which in other films encompass less heteronormative acts, such as oral sex. There are few concessions to female sexuality. When M barks an order to Moneypenny for her to relay to Bond - “Tell him to pull out immediately” - he inadvertently makes a pun about coitus interruptus. His words are focused on the agency of the male organ. And even though Moneypenny modifies M’s wording when messaging Bond - “007 to REPORT H.Q.” - Bond himself reinforces the connection between his penis and his duty to Queen and country when he tells the girl: “Something came up.” Is the implication that Bond is even more turned on by doing his duty than he is an attractive woman?

The heterosexist phallocentric world view is reinforced throughout the film with the fetishistic shots of penis-like war machinery: submarines, torpedoes, missiles.

But then it’s turned on its head when it’s revealed to be a giant tanker swallowing the submarines. This is a challenge to heteronormativity because the symbols of male virility (the bulbous-nosed submarines) are being overpowered by a ship with labia-like bows which open up and swallow them whole. And the tanker is aptly named: ‘labia’, the word for female genitalia, comes from the Latin for ‘lips’, which the Liparus quite literally has. (It was the Leparus in the original script, which is only marginally less on the nose.)

According to director Lewis Gilbert, the masculine symbol being swallowed by a feminine symbol intentionally recalled his previous Bond film, You Only Live Twice, which had space capsules being engulfed in a similar manner, reducing the male potency of the world powers they belong to. [If you think I’m taking this subtext too far, I warmly encourage you to read the work of Carol Cohn, a expert in the field of defence. This is dealt with in detail in the You Only Live Twice queer re-view, linked to above].

When the Liparus is destroyed, this does reassert male dominance, but for the whole third act of the film, a lot of the film’s tension relies on us feeling uncomfortable that the men may not end up on top. Bond and the crews of the UK and US submarines have been subjugated by a symbol of labial, feminine power. It’s curious that none of the crew of the Russian submarine are featured in the final battle. Are we to assume that they refused to give up and were all gassed to death by Stromberg’s men? Rather than a narrative gap, it’s far likelier they were omitted on purpose. If they had been present throughout the fight and ultimate victory, they would upset the schema of the whole film, diluting the film’s feeling of UK/US national pride.

Delving, desert and dessert

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. We’re still (for no good narrative reason) in the desert…

A delicious irony of the superfluous scene with Sheikh Hosein is Bond appearing “in full ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ garb” (as the screenplay puts it). Lawrence himself was, of course, a very queer figure who wrote openly about his same sex attraction and sadomasochistic desires. Later, the soundtrack quotes Maurice Jarre’s theme from David Lean’s film about Lawrence’s war time experiences. This was a tongue-in-cheek addition by a young editor assembling the film but the director found it so amusing it was kept in.

It’s not unusual for Bond to think of women as disposable pleasures (although it would take another thirty years for a woman to put it to him quite this bluntly on screen). But The Spy Who Loved Me pushes this disposability to extremes. In the very next scene, hundreds of miles away in Egypt but barely moments later in screentime, Bond finds himself in yet another honeytrap, although well-aware of it. Appearing to have fallen into the trap set by the “generously endowed” (from the screenplay again) Felicca, Bond commodifies hers as foodstuff (“I had lunch but I seemed to have missed dessert.”) before she is quickly dispatched, Bond throwing her in the path of Sandor’s bullet and dumping her, lifeless, onto the bed. You’re such a charmer, James!

The “dessert” line does not appear in the screenplay, perhaps being added during shooting. It draws our attention to the brief interval - in film time at least - since Bond last did some, er, delving. The screenplay does show that originally the scenes were in a different order, with Stromberg’s introduction coming in between the ‘delving’ and ‘dessert’ scenes, thus making it feel like Bond had more time to recover his, er, appetite. Although in the film’s scene, Bond is clearly more interested in information than sex, it contributes to the impression of Bond as a superheroic sex machine: the ultimate in straight male virility.

A spy who prefers women?!

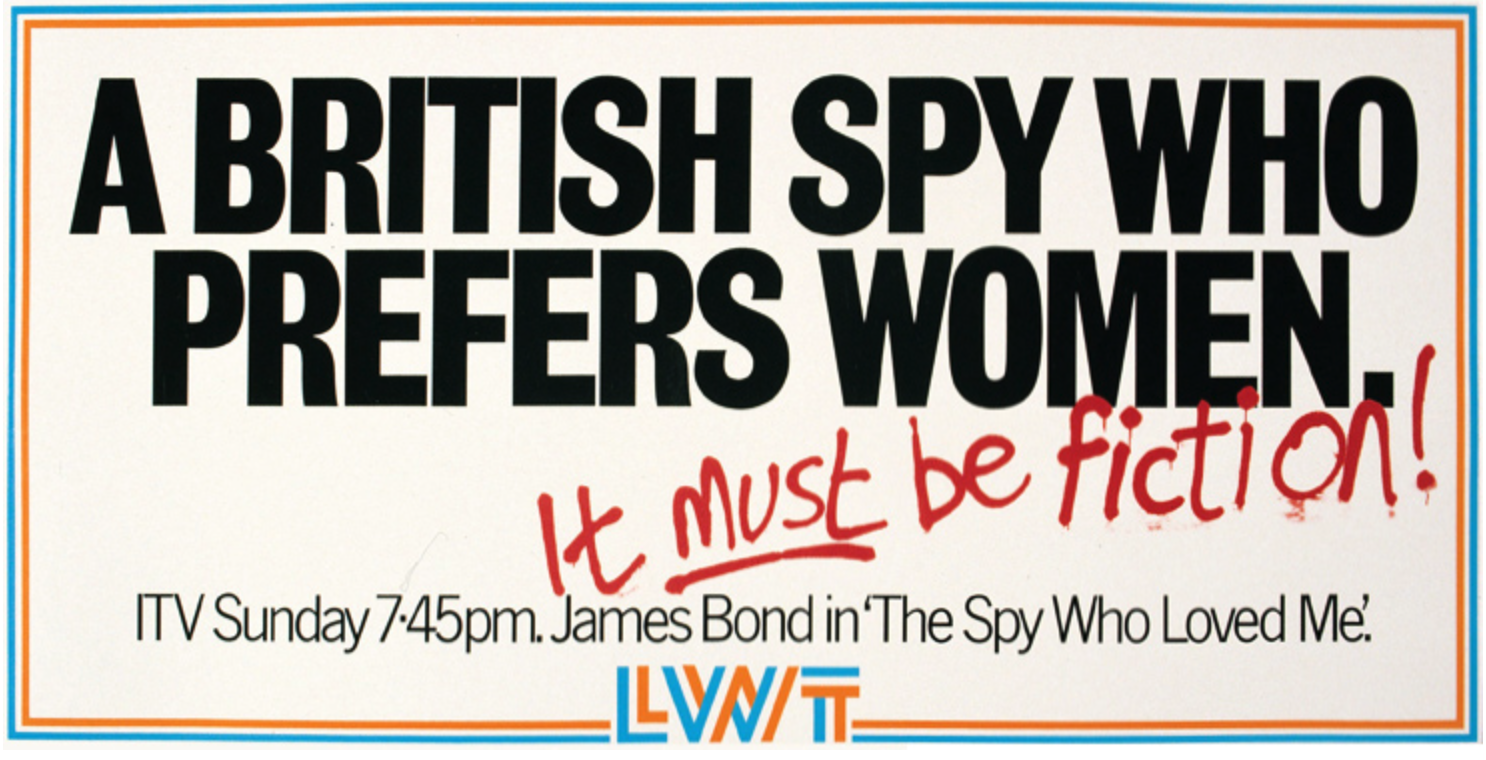

In the early 1980s, a British broadcaster promoted their upcoming TV screening of The Spy Who Loved Me with the following advert on billboards around London:

While this would be unthinkable today, it was a joke that would not have gone over the head of anyone living in Britain at the time.

According to 007 Magazine:

“London Weekend Television (ITV franchise holder for London and the Home Counties) often used the screenings of James Bond films to poke fun at the establishment during the 1980s and tied in the screenings with topical news stories of the day. Moles in the secret service and gay spy revelations were cleverly disguised as advertisements for the screening of the Bond film.”

By the 1980s, “gay spy revelations” were not particularly revelatory. Was anyone genuinely surprised when another one made the headlines?

Writing in 1997, espionage historian Phillip Knightley, asserted that “Right from their formation in 1909, Britain's secret services have been thick with homosexual officers, as has the opposition.” And while it would take until the 1990s for queer spies to be able to serve openly, “the secret worlds of spying and homosexuality have always gone well together.”

Bond himself emerged and thrived at a time when gayness and spying were inextricably linked in the public consciousness. Perhaps part of the success of the Bond character can be attributed to his novelty value - a straight spy! Who would have thought it?!

Only months before Fleming wrote Casino Royale, there had been the high profile defection of gay spymaster Guy Burgess, who is explicitly mentioned by Fleming in both From Russia, With Love and The Man With The Golden Gun. The scandal significantly informed the plot for the former. Gay spies were on the minds of cinemagoers when the film of From Russia With Love was released because of John Vassall, who was photographed by the KGB in compromising positions with men after being lured into a honeytrap by a mystery man he referred to as The Skier, which always brings to mind The Spy Who Loved Me’s Sergei (see discussion in Villains, below).

The KGB pulled similar honeytrap tricks with Jeremy Wolfenden in the 1960s, the son of the man who had given his name to the report recommending decriminalisation of homosexual acts. The younger Wolfenden came out to his father aged eighteen after being thrown out of Eton (shades of Bond!) for offering support and encouragement to other gay students. After university, he had been recruited by MI6.

Knightley gives a vivid account of what happened next, when he headed out to Moscow as a correspondent for The Daily Telegraph:

“The barber for the Soviet Ministry for Foreign Trade seduced Wolfenden on KGB orders. Just as they were going to bed in Wolfenden's room at the Ukraine Hotel, a KGB photographer jumped out of the wardrobe and said: "Allya, allya. Schta tut proiskhodit?" (literally, "Hello, hello. What's going on here?") as he photographed them.”

To his credit, Wolfenden told his MI6 bosses immediately and they asked him to be a triple agent. Although this did not become public knowledge at the time, when The Spy Who Loved Me was released, honeytrapping gay Western agents was a well-established tool in the KGB’s arsenal.

Between the release of The Spy Who Loved Me and its first TV broadcast (18th March 1982) another of the Cambridge Spies, Sir Anthony Blunt, was publicly outed.

In 1985, seven young British service personnel were put on trial for allegedly passing secrets to the enemy while stationed in Cyprus, having been discovered several years previously. They were, according to the prosecution, blackmailed into doing it, at least initially, after one of their number was photographed having sex with men. Although the trial (the longest and most expensive spy trial in British history) resulted in them being acquitted, it renewed the public’s association with gay sex scandals and spying. Being openly gay was of course illegal in both Military Intelligence and the British armed forces at this time.

There are, we are led to assume, no gay service personnel in The Spy Who Loved Me. Or at least no British ones. The film opens with a freshly awake Navy rating making his way from the bunks to the canteen. The screenplay for the film describes a scene prior to this where he is “reading a girlie magazine” and reacting with a (very Carry On-ish) “Cor!” to what he sees. What survives from the screenplay to the finished film is the walls “plentifully decorated with pin-ups”. Just in case we were at all uncertain, this is a hypermasculine heterosexual world.

The complexities of castration

In novelising his script, Christopher Wood took the opportunity to turn The Spy Who Loved Me into something Fleming might have written. The first half of the novel is notably different to the film and is quite revealing of the way the cinematic world of Bond had diverged from the books in order to move with the times.

The book features a particularly jarring and Fleming-like scene where Bond, captured by Anya’s male accomplices, torture him by sending electric shocks through his testicles. The description of Bond’s clothing being removed is uncomfortably homoerotic, akin to the carpet-beating of Casino Royale. It would take nearly three decades for the filmmakers to have the ba… er, gall, to put such a literal castration threat on film. Had they shown the Russians torturing Bond, representative of Britain, and with Bond eventually overcoming his torturers, it would have reinforced the film’s Rule Britannia sensibility. Writing about the way sexual violence is portrayed in the media, sociologist Dubravka Zarkov notes that:

“The castration of a single man of the ethnically defined enemy is symbolic appropriation of the masculinity of the whole group. Sexual humiliation of a man from another ethnicity is, thus, a proof of not only that he is a lesser man, but also that his ethnicity is a lesser ethnicity.”

By maintaining a functioning pair of testicles, Bond retains his British superiority over the weaker, and therefore feminised, Russian enemies. That at least one of the torturers appears to gain some kind of pleasure from his job (his eyes “glisten lasciviously” as he watches Bond’s underwear being removed by his partner) cements the connection between weakness and homosexuality. Bond emerges victorious, with his sexual organs and heterosexuality intact.

Tell him to pull out… immediately!

Let’s go back, for a final time, to that vitally important scene in Berngarten.

Like the film, the novelisation begins with Bond being almost honeytrapped by a beautiful spy. But it’s a far creepier scenario in the book: Bond discovers in a wardrobe the corpse of the chalet’s former female occupant before he even has a chance to get anywhere near a bed.

The film version of this event would appear to be more typically heteronormative and hypermasculine, with Bond getting the opportunity to enlargen the girl’s vocabulary by slipping his tongue into her mouth (a family-audience substitute for penis-in-vagina intercourse). And the aforementioned positioning of their figures reaffirms that Bond is in control. It appears to scream: not a hint of femininity here!

But wait:

Seconds after Bond has zipped up his bright yellow ski suit, we get a wry little musical flourish, or ‘sting’, on a muted trumpet, punctuating Bond’s statement that his country needs him. The moment could have been played sincerely, with a more heroic/nationalistic brass fanfare to reinforce the connection between nationalism and heterosexual masculinity. Instead, we get a wink to Hollywood’s Golden Age composers (Max Steiner, Erich Korngold) who would herald the arrival of British armed forces with such musical motifs. By 1977 it was a cliche, harking back to an earlier age. Therefore, the flourish undercuts any sense of male-posturing and nationalistic prowess. Bond, it says, and Britain, who he represents, are not to be taken entirely seriously. They are both relics of an earlier age. But crucially, this mickey-taking doesn’t prevent us from cheering when Bond’s Union Jack parachute opens up at the end of the sequence. If anything, the earlier musical moment actually gives us permission to relax and buy into the world of the film. Much as we might love both Bond and Britain they are not hallowed po-faced institutions. We can laugh at them, as well as with them. The Spy Who Loved Me gives us Jubilee-infused nationalism with a coating of iconoclasm. Even queer viewers, justifiably cautious of being betrayed by institutions, cannot help but feel a swelling of pride.

The film pulls the same trick right at the finale. At the risk of ruining a very funny punchline by over-explaining it, Bond telling the Minister of Defence that he’s “Keeping the British end up” is as much as about maintaining the preeminence of his nation as it is sustaining an erection, especially as he’s addressing his comment to his superiors.

But just as we might be at risk of construing Bond’s line as an assertion of his dominant, nationalistic, heterosexual masculinity, a sublimely silly arrangement of the title theme kicks in. The chorus of male voices makes me picture a crew of sailors camping it up like the titular Chorus Line in Marvin Hamlisch’s 1975 musical. It singularly subverts any sensation of jingoism and hypermasculinity, leaving the film wide open for queer appreciation.

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

In-keeping with Wood’s attempt to Fleming-ise his screenplay when he came to write the novelisation, the book features a far less sympathetic head of Russian Intelligence. Colonel-General Nikitin is definitely not an ally. Not only does he awkwardly make advances on Anya but, motivated by jealousy after she spurns him, he reveals to her that Bond is the one who killed Sergei, not only jeopardising Bond’s life but also the mission. Compared with Nikitin, General Gogol is an absolute sweetie. According to Ken Adam on the DVD commentary, Gogol’s office – where we first meet him - is inspired by the production design of films by incredibly influential queer filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. [While we’re on Eisenstein, the kidnapped Russian submarine, Potemkin, is named for Battleship Potemkin, Eisenstein’s most referenced and parodied film.]

Below: Eisenstein’s Ivan The Terrible (1944)

In a concession to the heteronormative ideal of ‘no sex before marriage’, Miss Moneypenny books a suite with separate bedrooms for Bond and Anya. Moneypenny’s over-efficiency (as Bond puts it) is more down to jealousy than anything else, again positioning Bond as the man all women want, consistent with the main thrust of the film.

Shady characters: Villains

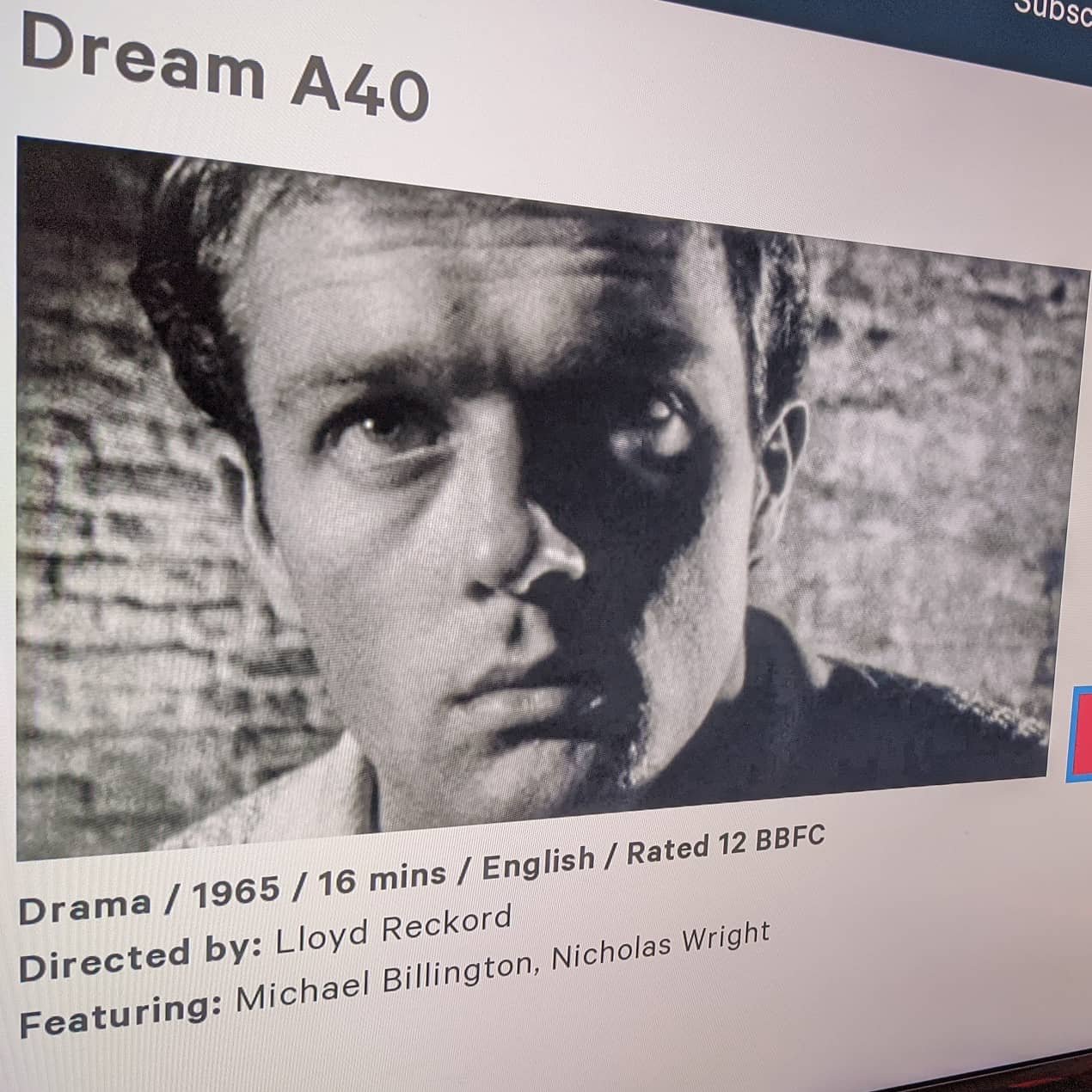

Anya’s boyfriend Sergei is played by the devastatingly attractive Michael Billington. A potential James Bond in his own right, his appearance in the film begins as a bluff, with his Connery-esque hirsute shoulders pulling back to reveal 007’s Russian double. Early in his career, Billington appeared in a 1965 short film entitled Dream A40 in which he played a gay man trapped in a nightmare after he and his boyfriend are arrested. It’s a captivating piece of film-making, especially considering it was made at a time when homosexual acts were still a criminal offence.

Carl Stromberg is a queer fish. In fact, he may even be a fish. In the film, the most obvious indicator is his webbed hands. In Wood’s novelisation - free of the constraint of having to cast an actor with an aquatic demeanour - he sustains the comparison, giving us the impression that Stromberg would take to living under the sea like a fish to, well, water!

Perhaps because I saw The Spy Who Loved Me for the first time around the time of the release of the Disney film, The Little Mermaid, I cannot help having a little smile to myself when Stromberg starts monologuing, imagining it’s Sebastian the Crab extolling the benefits of staying under the sea rather than Stromberg, particularly when he rhetorically asks Bond:

“Why do we seek to conquer space, when seven-tenths of our universe remains to be explored? The world beneath the sea.”

*It’s at this point the Calypso/Reggae-style music starts playing in my head*

Once you see Stromberg as a reversed version of Ariel the Little Mermaid, longing to be under the sea and not live on land, it’s hard to unsee it. Unlike Ariel, he has a very negative view of humankind:

Stromberg: I'm not interested in extortion. I intend to change the face of history.

Bond: By destroying the world?

Stromberg: By creating a world. A new and beautiful world beneath the sea.

*More Calypso/Reggae music in my head*

Stromberg: Today civilisation as we know it is corrupt and decadent. Inevitably, it will destroy itself. I'm merely accelerating the process.

Anya: That does not justify mass murder.

Stromberg: For that, Major, I will accept the judgment of posterity.

Stromberg is both kinds of misanthrope: the destructive misanthrope, who uses violence to bring about change, and the fugitive misanthrope, who wants to hide away from what he sees as a hostile world:

“I’m somewhat of a recluse. I wish to conduct my life on my own terms and in surroundings with which I can identify.”

It’s easy to see why queer people might identify with misanthropic recluses: why not turn your back on the society that doesn’t fully accept you? I’d be lying if I said that, as a kid, I didn’t sometimes fantasise about living the Stromberg life, in an undersea lair of my own creation. Pass the Tabasco!

It’s perhaps not surprising that a number of notable misanthropes and experts in misanthropy have been queer, including the novelist Gustav Flaubert (author of Madame Bovary) and same sex attracted Greek polymath Plato. Intriguingly, Stromberg names his submersible lair Atlantis, after the mythical, doomed Utopia which Plato wrote extensively about. It’s often been the case that those who have professed a hatred of humanity are just too idealistic; they get despondent when human beings fall short of their excessively high expectations. Misanthropy can be employed as a defence mechanism. Plato argued that it’s far healthier to accept that no one is perfect and that every human being is a mixture of good and bad.

One of the most influential misanthropes, the 17th Century philosopher Immanuel Kant, may have been queer. Cambridge Kant scholar Martin Sticker argues that although Kant appears quite homophobic by today’s standards, his philosophical framework is more open to same sex marriage than different sex marriage. Biographies of Kant note that he ‘never married’, perhaps an indication of predominantly same sex attraction.

Stromberg immerses himself in a queer world of his own design. On the walls of the Atlantis dining/conference room, Stromberg has several works by queer artist Boticelli, whose Bond pedigree dates back to Dr. No with the Venus-like arrival of Honey Ryder. And when disposing of duplicitous employees, Stromberg’s not averse to drowning out their screams with a nocturne by gay composer Frederic Chopin.

The impression we get is that Stromberg is almost literally a fish out of water. He might be object sexual in a similar way to Goldfinger, except rather than gold the object he has such affection for is water.

Who knows why Stromberg chooses to cut himself off from society? Well, perhaps historical precedent might have something to say about that. Professor of history and gender studies, Colin R. Johnson has discovered that:

“Throughout the nineteenth century the pages of American newspapers were filled with stories about misanthropic individuals who chose to sever all meaningful contact with their fellow countrymen and effectively withdraw from society. Referred to variously as hermits, recluses and occasionally misers, these individuals were notable in their day not only for their dislike of other people, but quite often for their very specific dislike of members of the opposite sex.”

Johnson argues that these recluses may have “presaged the emergence of modern homosexuality” and they were at least queer in the sense of being anti-social.

Long after his onscreen death, Carl Stromberg rests in our imaginations at the bottom of the ocean, the domain he adored. He also rests at the intersection of two camps of queer thought that have been battling it out for dominance since the late 1990s. On the one hand, you have a group of queer academics who have sometimes been branded ‘anti-relationists’ or ‘anti-socialists’ because they believe it is futile to attempt to assimilate with heteronormative society. They argue that retreating from social and political life is entirely justified because everything is geared to creating a better future for future generations. The idea is a pervasive one. Think of all the popular films, even those of recent years, which seek a satisfying ending by having a child - or several children - symbolise the only hope for a better future (Star Wars Episode III, A Quiet Place, No Time To Die) and you can understand where the anti-socialists are coming from. A very prominent anti-socialist, Lee Edelman, calls this ‘reproductive futurism’, and his statements on the subject are not without controversy.

Opponents of the anti-socialists argue that even those who cannot - or choose not to - have their own children should not be so ready to give up on Utopia. The relationists argue that you can still build a better world for everyone by challenging the status quo and forming communities of like-minded people. While many might find having children life-affirming (and society undoubtedly rewards those who do), it’s not the only way to live a satisfying life.

Stromberg’s situation is complicated somewhat if you consider a dark detail present in the novel but absent from the film. In the film, it appears Stromberg has been true to Bond villain type and taken the girl to be his own prize, changing her into a sexually provocative and revealing outfit along the way. Stromberg is a more sexual being in the film. Commensurate with the schema of the film, his final confrontation with Bond is framed, at least by Bond, as a mano-a-mano contest of sexual virility: “You’ve shot your bolt Stromberg. Now it’s my turn.” Compare this with the ending of Wood’s book, where Stromberg appears to be asexually coded. He tells Anya that he has taken her hostage not for his own sexual gratification but so she can bear the child of Jaws. Anya’s and Jaws’s offspring would have been the inheritors of Stromberg’s undersea world.

Jaws, all 7 feet and 4 inches of him, takes tenuous inspiration from a hoodlum who menaces the heroine in Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me novel (as does co-henchperson Sandor). Jaws’s teeth give his kills a homoerotic quality that goes well beyond standard Bond villain Othering. When he gives the fatal kiss to Max Kalber and Fekkesh, he exhibits a vampiric quality that Dracula and Nosferatu would be proud of. Vampirism has long been a queer metaphor, decades before Anne Rice got in on the act.

Watch the expressions on Bond’s face as Jaws tries to end his life by ‘kissing’ his neck. While his horror is justified (Jaws is forcing himself upon him) is there also revulson? Perhaps Moore’s performance anticipates the revulsion of straight men in the audience who fear they would be unmanned by getting intimate with another man.

In Wood’s novelisation, Jaws is more like another queer horror character: Frankenstein’s Monster. As well as a name (Zbigniew Krycsiwiki) Wood gives him a whole backstory which involves him being almost beaten to death before being rebuilt by Stromberg, partly in Stromberg’s own image (he also gets fishy characteristics, including an inability to speak).

An inability to reproduce naturally has long been used as a stick to beat many queer people with and the book adaptation throws itself into the deep-end, weaponising these fears to characterise the villains as Other. In comparison, the film only dips its toe in.

You go gurrrrrls

Like heaven above me / The spy who loved me / Is keeping all my secrets safe tonight

Along with ‘shaken and stirred’ and ‘for your eyes only’, ‘nobody does it better’ has become one of those phrases which are used synonymously with the Bond character. But just because a Bond song has a female vocalist it doesn’t mean we should assume it’s from a Bond girl’s point of view. It’s widely presumed that Nobody Does It Better is Anya singing about Bond and that’s the take I ran with in my discussion of Bond himself above. Similarly, writing in Rolling Stone, David Ehrlich described it as the “most satisfying” of all the “odes to Bond's sexual prowess”.

But I’m equally open to the idea that Carly Simon is not singing about Bond, but as Bond. In fact, the final shooting script indicates that the ‘spy’ of the title was intended to be Anya all along. Having escaped Atlantis, Bond raises a toast to Anya: “To the spy who loved me”.

This upends Fleming’s original novel, which had Bond, very much the titular spy, entering the life of a civilian woman. With two spies as the film’s leads, the film allows us to make up our own mind - or just accept both may be the case. After all, it rarely pays to be so binary about these sorts of things.

Anya is the first of the series’ ‘female James Bond’ characters and her introduction allows her to slip into 007’s shoes as easily as she – eventually – slips between his sheets. The film openly challenges our gender expectations, wrongfooting us by making us think boyfriend Sergei is the top KGB spy before identifying her as the worthy adversary. According to the film’s DVD commentary, the dead boyfriend was a late addition to the script, but it’s a crucial one. Although she is clearly attached to Sergei, her ability to move past his death puts her on an even-footing with Bond: the impression we’re left with as the credits roll is that Triple X is just as likely to love ‘em and leave ‘em as 007 is.

Besides writing two Bond films, Christopher Wood is most famous for penning a series of four Confessions Of… films, starting with Confessions Of A Window Cleaner (co-written with Val Guest, a director of Casino Royale 67). The films relate the experiences of Timmy, who is sexually inexperienced and somewhat inept in the bedroom department. Nevertheless, he finds himself in a variety of awkward compromising situations with sexually adventurous women. The humour results from this reversal of gender expectations.

You could argue that a similar dynamic is at the heart of The Spy Who Loved Me: for all his arrogance, and perhaps because of it, Bond is often the target of the film’s humour. Anya openly mocks Bond for his signature pretensions. For instance, she follows up her shaking-up of Jaws with a punchline appropriating Bond’s fussy famous Martini preference: “Shaken but not stirred.”

In Wood’s novelisation, we are told the agency for which Anya works (which in the novel is SMERSH, rather than the KGB) employs men, women and “transvestites” (although Wood, emulating Fleming, perhaps intends his readers to find this Othering, rather than a sign that the organisation is progressive in its hiring practices).

Also in the novel – and less explicitly in the film – we are told that Anya has been trained to use sex as a weapon, another thing putting her on a par with Bond. She also uses her bra as a bandage after Bond is injured by Jaws, which would have been an interesting inclusion in the film!

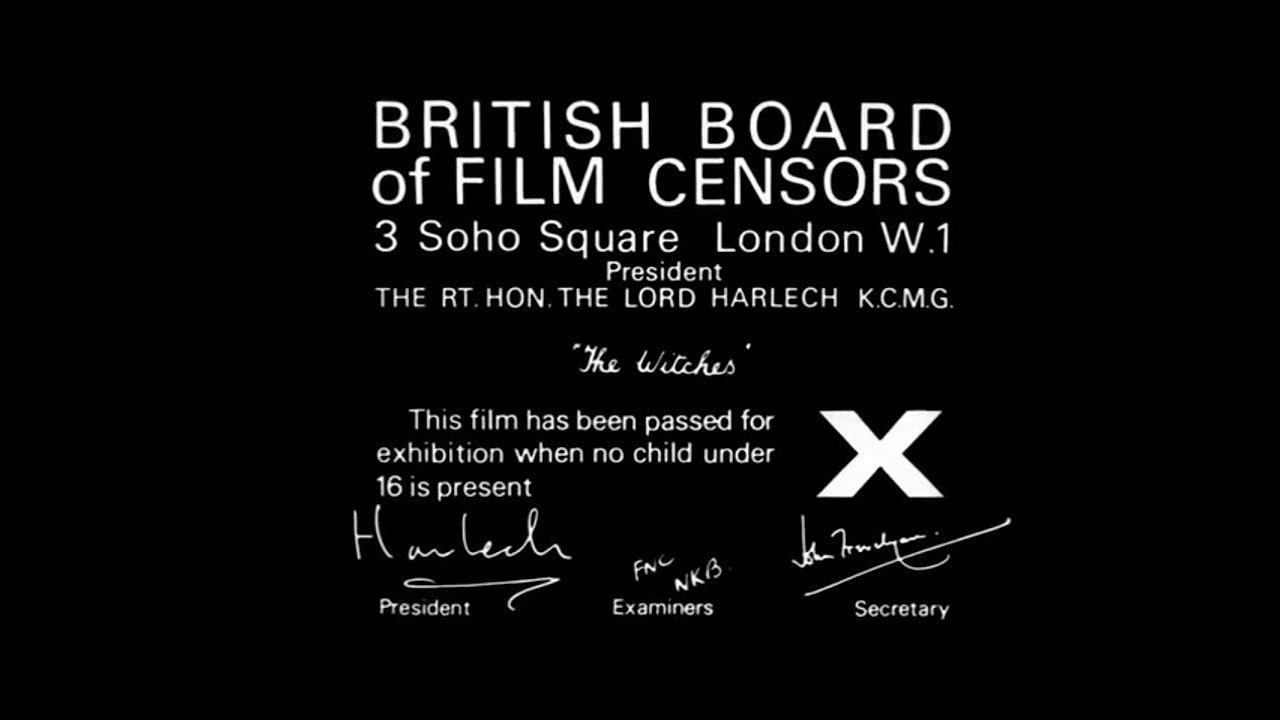

Anya is given the code name XXX, associating her with sexually explicit activity, certainly in the mind of British cinemagoers. The X certificate was introduced by British film censors in 1951 and continued until 1982, being replaced by the ‘18’ rating, which was far less sexually suggestive. The Secretary of the British Board of Film Classification himself, John Trevelyan (a very Bondian name there), admitted it was a mistake to ever use ‘X’ as a rating because it rhymed with ‘sex’ and therefore made younger people want to see these films all the more. There has never been an XXX certificate - this was merely a marketing gimmick by porn producers and distributors who wanted to advertise their works as more sexually explicit.

I always find Bond making Anya jealous of Naomi a particularly insensitive move on his part (“What a handsome craft. Such lovely lines.”). In my mind, I always misremember this part of the film, imagining it being Anya firing the Lotus’s missile at Naomi’s helicopter, literally eliminating the competition. While this would have been satisfying for Anya, it might have also weakened her character, making it appear that she was all that bothered by Bond’s interest in another woman? And what would it have said about her appropriating Bond’s weapon to destroy her rival, as she does later in the scene where she presses the Lotus’s buttons? I’ve had my fill of phallic symbols by this point so I’ll let you make up your own mind.

Anya’s unabashedly feminine presence on board a nuclear submarine satirises the phallocentrism of Navy life (Shane Rimmer’s second in command acts as if seeing the naked female form is an entirely new experience for him). Later, when the crew of the USS Wayne is forced to disembark on the Liparus, Bond insists Anya make an attempt to conceal her long hair (common signifier of femininity) with a cap. Her being discovered to be a woman by Stromberg’s crew is what gives her and Bond’s game away.

In the novelisation, Bond has the opportunity to save the world by shooting down Stromberg’s helicopter as it leaves the deck of the Liparus. He holds his fire because he doesn’t want to also kill Anya, who has been taken prisoner by Stromberg. The same idea survived in the film but the stakes are merely personal: Bond has already reprogrammed the nuclear submarines to destroy each other by the time he Is forced to make a decision about saving Anya. In the film, Bond boards the soon-to-be-torpedoed lair solely to rescue Anya. It’s a more romantic finale and really establishes the détente idea which will be developed over the next two decades of Bond movies, right up until The Living Daylights and GoldenEye, prefiguring the real life easing of tensions between nations as the Cold War (or at least the first one!) petered out.

Yasssss queen

With Britishness beginning and ending the film and Union Flags everywhere, Bond’s motivation in The Spy Who Loved Me is more obviously Queen and Country than in most other entries. Although we don’t see Queen Elizabeth II on screen except as a portrait, the film was made in the run up to the Silver Jubilee and this undoubtedly guided certain choices during the production, as the Platinum Jubilee would influence Skyfall 35 years later, with the Queen becoming an actual Bond Girl in the short film made for the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics.

A lot of gay men have a kinship with queens and princesses. Perhaps because royals such as Queen Elizabeth II, Princess Diana and Queen Victoria had to assert themselves in a man’s world, men who don’t identify as conventionally masculine can identify with them easily. When the first Queen Elizabeth addressed the land army assembled in the eventuality of the Spanish Armada breaking through she addressed the elephant in the room: “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman but I have the heart and stomach of a king”. Wearing your X chromosomes on your sleeve before telling your audience they’re of no consequence is a clever rhetorical move, to be sure.

Conversely, it’s understandable why many queer people might not be fans of the Royal Family: they are very visible symbols of The Establishment, something queer people have not always felt a part of. The year after The Spy Who Loved Me, gay filmmaker Derek Jarman released Jubilee, his scatching critique of British jingoistic sentiment, motivated by his anger at the Conservative government.

The film paints the royals themselves in a decent light: its heroine is the first Queen Elizabeth, travelling forwards through time to 1978 to examine how her queendom has turned apocalyptic. She’s accompanied by her trusted advisor/spy John Dee who has often been labelled as ‘the original 007’, not least because he prefixed all his secret communiques to Elizabeth with the number 007, the 0s representing a pair of eyes (for her eyes only). Henry Chancellor is rightly sceptical of this theory and all of the other alleged origins of Bond’s code number, including the one put forward by Fleming himself. Perhaps the Dee theory is largely unquestioned because of his Bond-like connections with nationhood, the two being inextricably linked in many minds: Dee is credited with coining the term ‘British Empire’.

Whether you’re a royalist or not, the fact is that today’s Royal Family has, like any other, queer members. The Queen’s favourite cousin, Lord Mountbatten, married a man in 2018 (although he spent fifty years in the closet first). And in 2019 Prince William told an interviewer that he would “fully support” his children if they were gay, although he did admit that he was worried about, as a parent, “how many barriers, hateful words, persecution, all that, and discrimination that might come” and his family’s “position” might make things difficult. If a future king or queen of England was gay, they wouldn’t be the first one. The official website of the Historic Royal Palaces has a whole section dedicated to rulers who were likely queer - including Edward II, James I, Charles I, Queen Anne - as well as their courtiers. The page concludes: “It is too easy to assume that everybody in the past was straight unless we have clear proof otherwise, but we know this is not the case.”

Almost all of Bond’s missions have taken place during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, meaning he has been in the service of a female boss all along, something he appears to have no issue with. If only all men could follow his example.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

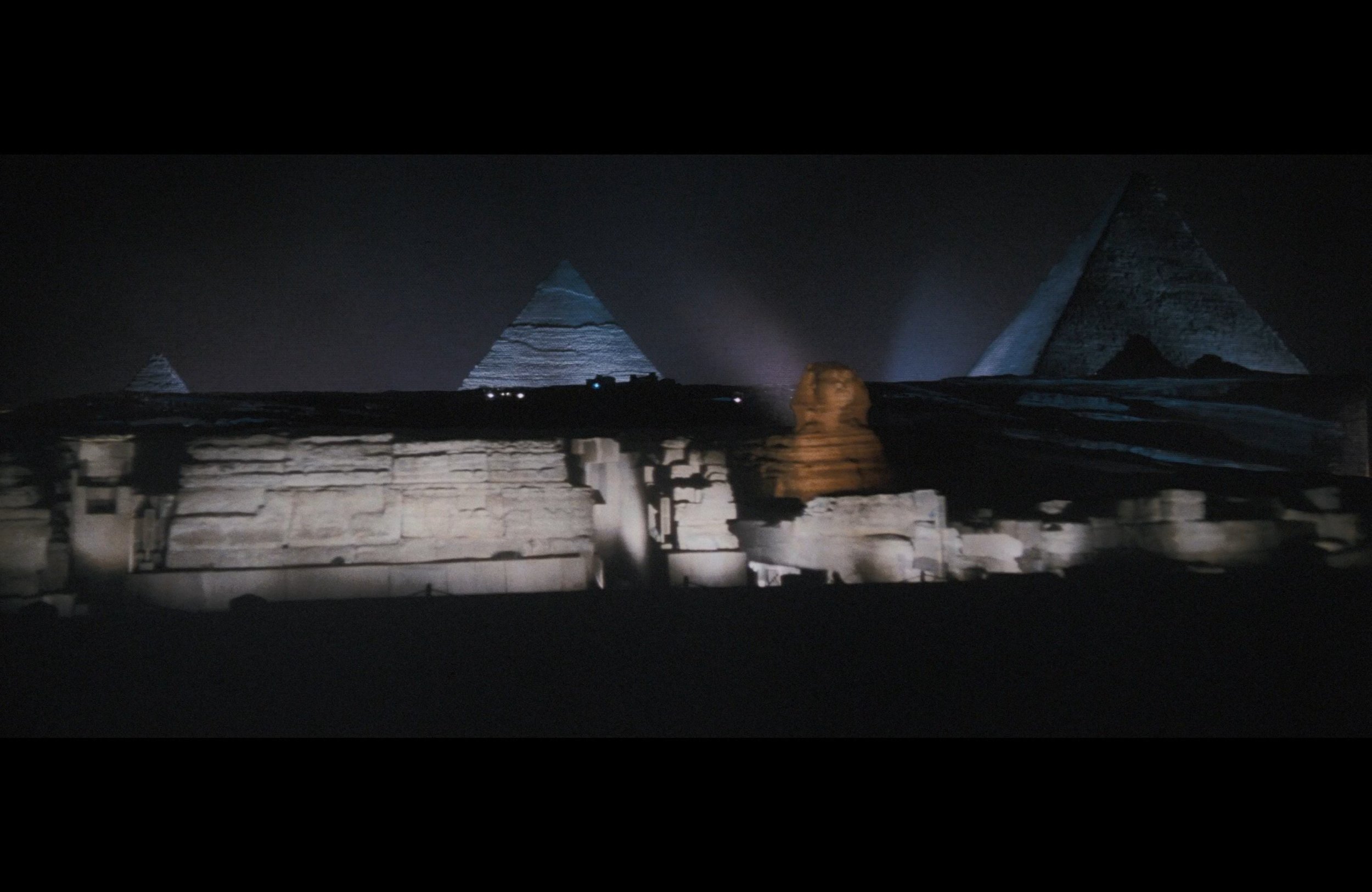

Two time Bond acting alumnus Charles Gray (Henderson in You Only Live Twice, Blofeld in Diamonds Are Forever) supplies some of the voiceover for the son et lumiere show where Fekkesh meets his end. By this point, the gay actor had also starred in the queer classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

The son et lumiere scene takes place in the shadow of the Sphinx which Wood describes in his novel as “sexually ambiguous”. He’s correct to do so. These mythical creatures, with the head of a human, the body of a lion and wings of a falcon, are usually presented as androgynous. The Greeks mostly came down on the side of presenting them as women, the Egyptians mostly went with men so let’s meet somewhere in the middle.

There are a lot of hot Bond boys with bit parts in The Spy Who Loved Me, but one above else has always stood out to me: the unnamed HMS Ranger Crewman played by Kim Fortune. His tragic, heroic demise as he leads the force attempting to penetrate the blast doors on the Liparus only endears him to me more. Despite his fleeting screentime, he left a very strong impression on this adolescent gay Bond fan.

Moore’s Bond is widely considered more Camp than any of the others, before or since, helpfully illustrating that Camp and gay do not always coincide. Setting the Don Juan-like hypersexuality aside (are you trying to prove something, James?), it would be a losing battle from the outset to make a case for the Bond of The Spy Who Loved Me as being anything other than straight.

Every interaction with a woman has a sexual frisson. Witness Bond’s exchange with Valerie Leon’s hotel receptionist:

Receptionist: “I have a message for you.”

Bond (looking approvingly): “I think you just delivered it.”

Moore’s Bond is not effete in the rich British tradition of Camp (and gay) comedians like Kenneth Williams, Larry Grayson and Julian Clary. He’s Camp because we are not intended to take him seriously. It’s sheer escapism, darling!

Compare Bond here with the Bond of The Man With The Golden Gun. While the 1974 film is hardly the most navel-gazing entry in the Bond canon (although it does feature some charming gazing at an actual navel), Bond himself has some self-doubt in that film and he certainly makes more mistakes. Three years later, we get little more vulnerability than a quickly forgotten sensitivity about his dead wife (Anya: “You’re sensitive Mr Bond.” Bond: “About certain things yes.”). This angle is pushed a little more in Wood’s novelisation, with Bond’s internal monologue questioning whether he’s falling for Anya, as he had previously fallen for Tracy.

When Lewis Gilbert was asked to outline his vision for The Spy Who Loved Me, he told producers they needed to “stop trying to make Moore into Connery” but he could have added “and Lazenby”. Gilbert brings Moore’s suave sensibility to the fore in The Spy Who Loved Me. Right from the outset, it’s pure fantasy. Moore makes the life of a spy seem eminently appealing to all.

After a career of covering espionage stories for various publications and getting to know many real spies personally, Phillip Knightley reflected on the attraction of the profession, one of the oldest in the world:

“Once you overcome your scruples about reading other people's letters, eavesdropping on their conversations, burgling their premises, exploiting their character weaknesses, and blackmailing and betraying them, it's the perfect job. A life of travel, adventure, and authorised sex, with a flexible expense account (informers don't give receipts) can be attractive to bachelors of either persuasion.”

Despite the film’s title, Bond does very little actual spying in The Spy Who Loved Me and far more travel, adventure and sex. Although we may not necessarily connect with this film’s Bond on any deep psychological level, the wish fulfillment he embodies appeals to the hedonist in all of us.

Queer Verdict: 003 (out of 007)

While the film ultimately rejects the possibility of a 'female 007’ coming out on top, it’s not the uncomplicated celebration of macho British masculinity it first appears to be. Whoever we are, whatever our preferences, there’s some kind of magic that stirs inside when we see that Union Jack unfurling.

References

007 Magazine (2022) ‘007 on the small screen’ Available at: http://www.007magazine.co.uk/bond_on_tv.htm

BFI (2022) ‘The X Certificate’ BFI ScreenOnline Available at: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/591679/index.html

Chancellor, H (2005) James Bond: The Man and His World London: John Murray

Dangerfield, D. T. 2nd et al. ‘Sexual Positioning Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Narrative Review.” Archives of sexual behavior vol. 46,4 (2017): 869-884

Edelman, L (2004) No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive Durham: Duke University Press

Johnson, C.R. (2013) ‘Unfriendly Thresholds: On Queerness and Misanthropy in Nineteenth-Century’ America Conference: 127th Annual Meeting American Historical Association January 2013

Freyd, J (2022) ‘Institutional Betrayal and Institutional Courage’ Institutional Betrayal Research Home Page Available at: https://dynamic.uoregon.edu/jjf/institutionalbetrayal/

Knightley, P (1997) ‘So what’s new about gay spies?’ The Independent 1st June 1997 Available: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/so-what-s-new-about-gay-spies-1253692.html

Lane, S (1996) ‘Wolfenden - The Man, The Report, The Legacy’ Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada Available at: https://lglc.ca/essays/lane-wolfendenmanreportlegacy

Nagel, J. (1998). Masculinity and nationalism: Gender and sexuality in the making of nations. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21(2), 242–269.

Puar, J (2007) Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times Tenth Edition Durham: Duke University Press

Plummer, D. The Ebb and Flow of Homophobia: a Gender Taboo Theory. Sex Roles 71, 126–136 (2014)

Rosen, R (2014) ‘A Glimpse Into 1970s Gay Activism’ The Atlantic 26th February 2014 Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/02/a-glimpse-into-1970s-gay-activism/284077/

Ruti, M (2017) The Ethics of Opting Out: Queer Theory's Defiant Subjects New York: Columbia University Press

Said, E (1978) Orientalism London: Penguin

Schelsinger, H.R. (2021) Honey Trapped: Sex, Betrayal and Weaponized Love Cheltenham: The History Press

Slootmaeckers, K (2019) Nationalism as competing masculinities: homophobia as a technology of othering for hetero- and homonationalism. Theory and Society (2019) 48:239–265

Watchmaker Productions (1997) ‘What a performance!’ Documentary Available at: https://youtu.be/2lI3B8Ns7ko

Zarkov, D. (2001). The body of the other man: Sexual violence and the construction of masculinity, sexuality and ethnicity in the Croatian media. In C. O. N. Moser & F. C. Clark (Eds.), Victims, perpetrators or actors? Gender, armed conflict and political violence (pp. 69–82). London: Zed Books.

The DVD/Blu Ray commentary, featuring Lewis Gilbert, Christopher Wood, Ken Adam and Michael G. Wilson was helpful for behind the scenes details.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sam Rogers who raised the possibility of Stromberg being object sexual.

Stu Rolls sent me the link to the documentary on Camp comedy which is a delight. Watch it!

Analysing the trumpet flourish (or is it a fanfare? Or a sting? Or a motif? Or all of these?) was a team effort. Particular thanks to Chris Malone of Malone Digital (who has worked on some of my favourite soundtrack re-releases) whose analysis I have mostly gone with. Also thanks to the folliowing, who pitched in their thoughts about a brief, but pivotal, moment: Tom Mason, Scott from Spy Hards, novelist Danny Marshall, Stu Perrins, David Fox, ‘You’re Gonna Need a Bigger Boat’, Chris @GelNerd, Jordan Welsh, Dorian Gray, Marcus Petaja, TheWizardOfIce, Stephen Barber, Jon Auty of Behind The Stunts, Mark O’Connell and Ben Williams.

Thank you to Claire Birkenshaw for introducing me to the term institutional betrayal. Although I only touch on it here, it has sown the seed for a queer re-view of a later Bond film which has many similarities with The Spy Who Loved Me.