Queer re-view: Casino Royale (1967)

Have no fear, James Bonds (plural) are here! Far from a ‘straight’ take on a Bond story, the ‘67 Casino Royale is much maligned. But in many ways, it’s well ahead of its time. Whether by accident or design, it’s an experience which is not merely open to queer readings, but warmly welcomes them in. Leave at the door your pre-conceptions about what ‘James Bond’ is or isn’t and prepare to join what the original trailers called “the Casino Royale fun movement”.

I’ll admit that getting to grips with the 1967 Casino Royale was low down my ‘to do’ list when I started Licence To Queer. I reckoned I’d last seen the film around twenty years ago and I was hesitant to repeat the experience, in large part because I knew it was far from adored by most in the Bond community. Mostly though it was because I hazily remembered enjoying at least parts of it as a child and I didn’t want to taint my memories. I don’t usually allow my personal feelings (the negative ones at least) about any film to intrude too much in my writing. I think it’s bad form to disregard any film because I don’t personally like it. Any film is, after all, the work of thousands of people. And in Casino Royale’s case there were more people involved than usual, including five directors and dozens of writers. Casino Royale was a chaotic production by all accounts. The most detailed account is that found in Michael Richardson’s book, The Making of Casino Royale (1967) which I strongly recommend. While this isn’t the place to repeat a lot of that material, it has been pertinent at various points to reflect on how the ‘too many cooks’ approach to the production led to some queering of the finished outcome, intentionally or not.

Those who know the film but not the production history may be surprised to learn that some of the original ideas for the film were even more maniacal than what ended up on screen (my favourite idea from an early script is the male casino employees unzipping their clothing to reveal they were ‘killer girls’ all along!). In this piece, I have confined myself largely to what ended up in the finished two hour film however. The film’s disjointed feeling, particularly in the final third, is not down to merely Peter Sellers walking off the set before the film was finished. Over an hour of material was cut in advance of the premiere and it’s unlikely this will ever be found.

Cutting the film down worked - financially at least. Some are surprised to learn that Casino Royale was very successful on initial release. It definitely appealed to a wide audience, some of whom would have been queer. At times, I have tried to imagine how they felt watching a Bond film which, in many ways, was queerer than the increasingly homogenised ‘official’ Eon entries starring Sean Connery. There’s a plurality to almost every character’s identity in Casino Royale. Everything is less stable and fixed, reflecting real life social change. 1967 was the year homosexuality was partially decriminalised in the UK and, while men who were attracted to other men were far from equal in the eyes of the law, this may have led to a feeling that more possibilities were opening up.

Even taking this into account, I was still reluctant to go near Casino Royale until a conversation with one of its passionate advocates pushed me over the edge. For long-time Licence To Queer reader Lotte:

“The whole experience of watching it is queer. It isn't perfect, there is a lot wrong with it. Some of that was from design, most from self-destruction, but it's a different way to watch Bond. Even Never Say Never Again followed the Eon formula. It's like we're used to the heteronormativity of Bond films [so we don’t know] how to fit Casino Royale ‘67 into the Bond world. It's constantly dismissed by Bond fans.”

More of Lotte’s comments appear throughout this piece. Thank you Lotte - I would not, and could not, have done it without you.

Method in the madness

If this is your first time reading a queer re-view on Licence To Queer… you are probably in the same boat as regular readers this time around!

Regular readers will know I usually chunk up my analysis across five discrete sections: Bond, Allies, Villains, Girls and Camp. The methodology is explained here. And while I have attempted to do this with Casino Royale, it stubbornly - commendably even! - resists attempts to categorise it along these conventional lines. Like the film’s plot threads, its characters’ identities intermingle, getting caught up with each other, twisting and changing. This is most apparent in the characters of Bond him/herself. There are at least seven Bonds, four of them being women. And while it would be possible to distribute each Bond across the usual sections - Allies, Villains, Girls - it hardly seems fair. They are all ‘James Bond 007’. Therefore, it felt more fitting to deal with them AS Bond, taking each in turn, in the order they appear in the film.

“The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond?”

“The plot of the film (yes, there is a plot) is wonderful. Anyone can be Bond.” - Lotte (Licence To Queer contributor)

“This is too much for one James Bond,” the posters and trailers declared. While such multiplicity incenses some fans, for others it raises the entertaining possibility: could any of us be James Bond, regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation?

Bond 1: Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers)

Let’s begin at the - very queer - beginning.

Our first Bond is introduced loitering languidly in a pissoir, the street toilets which once littered Paris streets but were on their way out by the time of Casino Royale’s release. These facilities had been used for secret meetings between members of the Resistance during the Second World War and were still synonymous with casual sexual encounters between men. Audiences at the time were more likely to be familiar with pissoirs, so their first thoughts might have ran something like this: why is Bond waiting around in the loo? Who is he waiting for? Is he… cruising?

This will not be the last time that we are introduced to a new Bond in a men’s bathroom. Nearly three decades later, Brosnan’s Bond drops in on an on-the-job Russian soldier. And in the ‘official’ 2006 Casino Royale, Craig completes his first Double-0 kill by smashing his opponent into a row of urinals before unloading his weapon into his face.

Okay, you don’t need to be queer to get the idea.

I have explored the (surprisingly voluminous) literature on the meanings of men’s bathrooms several times already (as well as my re-views of GoldenEye and Casino Royale 2006 see The Living Daylights). When I was younger, these meanings went completely over my head. And the last time I watched Casino Royale I was a teenager. I remember finding the opening disappointingly unremarkable. Especially compared with those in the ‘official’ series of films, t’s a pretty unprepossessing pre-titles sequence. That is, unless you take it as a gay joke.

It turns out that it’s Mathis that Bond is waiting for. Mathis establishes his identity - after shiftily looking around to check no one’s watching - by showing Bond his “credentials”. As we only see the top half of both figures, it’s entirely credible that we are supposed to take this as Mathis showing Bond more than just his ID. Sellers’ eye-line (aimed at Mathis’s crotch) is intended to sell the joke.

This pre-titles sequence, it transpires, is a flash-forward. It shows a more confident Tremble as Bond, living his dream of playing the superspy. For Lotte, Tremble is an “everyman” character who allows the audience to play at being Bond, “a bit like Sellers himself”. When we first meet the aptly-named Tremble he’s “awkward with the ladies, but great with cards… a nerd who wrote a book… flawed, insecure”.

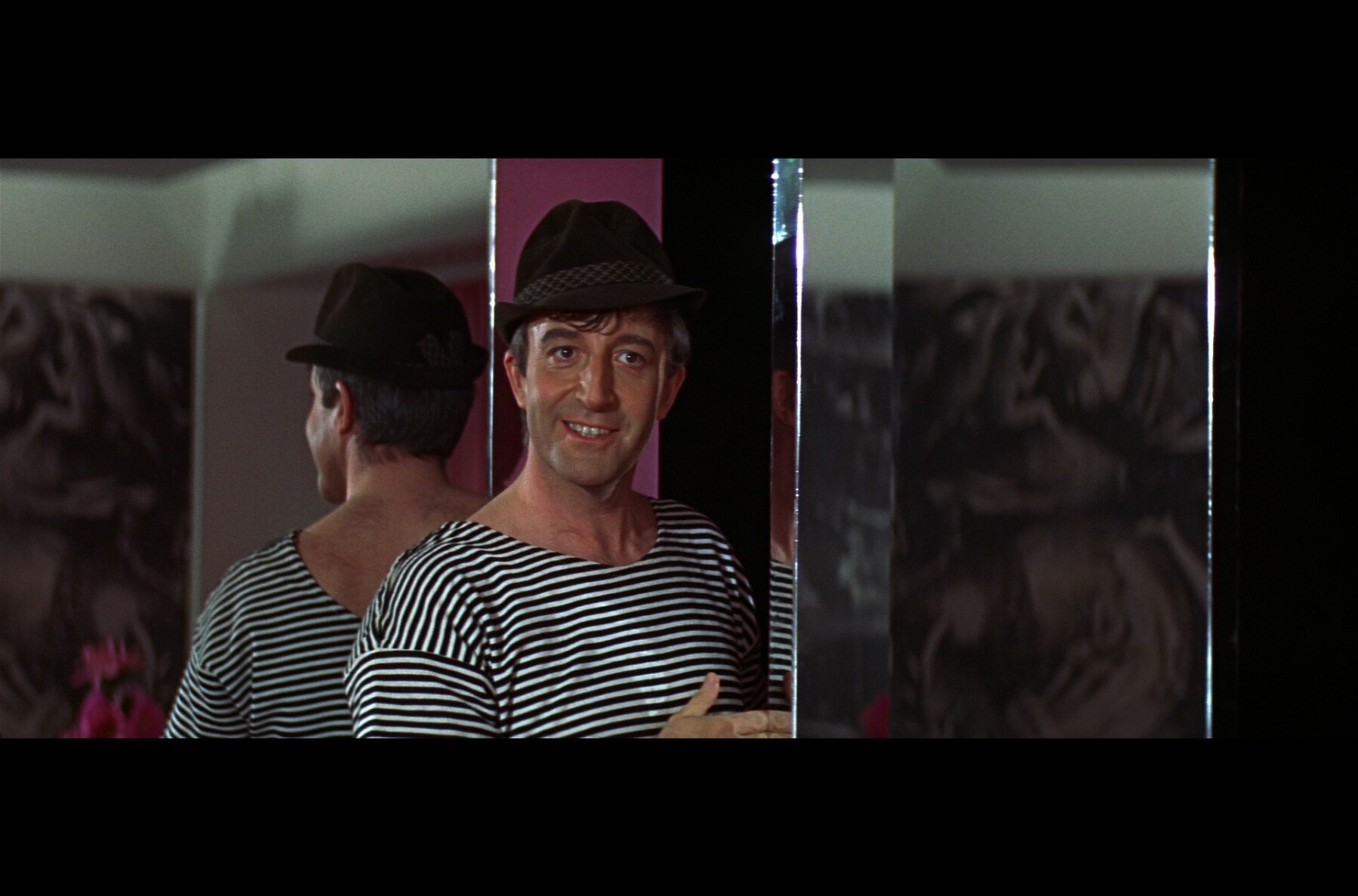

Tremble gets a sort of gender-reversed Pygmalion treatment at the hands of Vesper Lynd, who tears him apart and rebuilds him as comparatively manly James Bond 007, starting with his nomenclature (“Isn’t Evelyn a girls’ name?”). In the ‘Look of Love’ sequence in Vesper’s apartment, we see Tremble through her eyes and he’s shown in the same soft focus that she is. He is overtly feminised and even camps it up (“Hello sailor!”) as he tries on a variety of outfits, although this probably has more to do with Sellers’ desire to showcase his range rather than any conscious queer-coding on the part of the scriptwriters. This sequence also calls to my mind similar photoshoots in Antonioni’s Blow-Up, released the previous year. The key difference is that it’s a woman, Vesper, behind the camera, gazing on a man.

Ultimately, the tremulous Tremble’s transformation into his hypermasculine Bond persona requires more than just clothing: it requires a ‘rite of passage’. And the rite itself is an act of violence, just as it would be for Daniel Craig in the ‘two kills’ pre-credits sequence of the 2006 Casino Royale. In Tremble’s case, he punches a customs agent, despite not being provoked in any way, which although not lethal like Daniel Craig shooting Dryden in his office, is just as disproportionately, cold-bloodedly violent.

Also true to traditional Bond form, Tremble falls prey to an enemy female agent, Miss Goodthighs. In another uncanny parallel with the 2006 Casino Royale, he is rescued by Vesper after having his drink spiked by a villainous girl. Whereas Craig’s Bond shrugs off the murder attempt by changing his shirt and re-joining the poker game, Tremble receives an admonishment from Vesper and berates him for not keeping up his hypermasculine appearance: “James Bond doesn’t wear glasses!”

Even today in the world of Bond, it’s a safe bet that any man in a movie who wears glasses (other than sunglasses) is probably either a desexualised nerd or coded as queer (both in the case of Ben Whishaw’s Q).

Tremble’s Bond is created by Vesper so it’s arguably fitting that she’s the one to end him. While in reality, the character’s death is the result of Sellers walking off set before filming was completed and never returning, it accidentally provides another example of a queer character being buried before the end credits.

Although in this Bond movie, he’s hardly alone in meeting a premature end...

Bond 2: Sir James Bond

The real James Bond, according to Casino Royale, is a retired veteran of some of the British Empire’s most lauded campaigns, including the First World War, who now spends his afternoons playing Debussy and eating Royal Jelly.

Quite what the writers were suggesting about Bond by making him an avid eater of bee secretion is unclear but there’s definitely more to it than just the bees. More like, the birds and the bees...

By itself, the word ‘jelly’ has been commonly used as synonym for ‘semen’ since at least the early 1600s: it appears with this sense in a 1622 play by Shakespeare-collaborator John Fletcher. It carried its sexual connotations through to blues and jazz in the early 20th Century. The famous musician ‘Jelly Roll’ Morton acquired his name early in his career when he played music in brothels to aurally lubricate sexual liaisons. Although it’s understandably difficult to locate a reliable written source, the proper noun ‘Royal Jelly’ has, at various points, been used by to refer to semen or natural lubricant secreted in the anus during intercourse. Today it is still marketed as a natural aphrodisiac which increases male potency and there is some scientific basis for this. We should be cautious about drawing anything other than a very tentative conclusion about a passing reference in a script which was cobbled together by a veritable army of writers, often at quite short notice. But it suggests that either Bond is queerly effete or battling impotence.

Before we meet Sir James, M paints him as a “pure spy”, an Adam who lives an existence unsullied by Eve, something Legrand from the Deuxieme Bureau cannot comprehend: “Eden without an Eve is an absurdity.” Sir James is proud of his celibacy, decrying the “bounder” who he gave his name and number (the James Bond from the Eon films) as a “sexual acrobat who leaves a trail of beautiful dead women like blown roses behind him”.

And yet, is he really that different? A real-life woman - Mata Hari - ended up dead because of Sir James’s actions. She was “the woman in his life” and by choosing his duty (handing her to the authorities to be shot) over her he turned down the chance of a heteronormative happy ending.

Casino Royale is overstuffed with plotlines and characters, but if one could delineate a single dramatic idea that carries through the running time, it is the tension between giving in to one’s desires and exercising self-control. Two years before Casino Royale, many of the same cast and crew worked on What’s New Pussycat?, a sex comedy with the same central preoccupation. The difference there was that the hero of the story had an unequivocally strong libido and was trying (not very hard) to tame it so he could enter settled domesticity with one woman.

As part of my research for this article I watched What’s New Pussycat? for the first time and found it to be a deeply unfunny experience, and I’m not alone. In his essay included with the 2019 Blu-Ray release, Simon Ward identifies the problem with the film: “An Englishman who is a sexual titan is not a tried and tested character trope. James Bond, yes, but not in a comedy.” Instead, British audiences “favour underdogs and heroes who never quite come out on top”.

Compared with What’s New Pussycat?, Casino Royale is Citizen Kane. Royale is more effective because it’s funny (at least in fiction!) to have character with little or no libido being pursued by armies of people who want to have sex with him. As Sir James himself complains: “Female spies harassed me in Scotland, female spies chased me to London.” Casino Royale’s protagonist is presented as (voluntarily) celibate. He throws into sharp, comic relief the Bond of the books and the Eon films series. When Sir James Bond takes charge of the Secret Service, he laments that “It’s depressing that the words ‘secret agent’ have become synonymous with ‘sex maniac’”, a clear dig at the established character we are familiar with.

James Bond’s penis has received more than its fair amount of attention, academically and otherwise. Toby Miller puts it to great use in an essay on Bond and cultural imperialism in which he notes that, while potent in some regards, “Bond’s penis is a threat to him-a means of being known and of losing authority”. Although Miller does not invoke the 1967 Casino Royale in his essay, the film makes this literal, with Sir James Bond bemoaning the fact that so many agents have been assassinated while ‘on the job’ (as it were) in places of ill-repute, with one “stabbed to death in a ladies’ sauna bath”, another “burnt in a blazing bordello” and another “garrotted in a geisha house”. The conclusion appears to be: Heterosexuality is dangerous in the world of Casino Royale. To reduce the risk to their agents, Sir James sows confusion by renaming all agents ‘James Bond 007’ - man or woman. The Eon James Bond’s penis is a liability so it’s best to give his name to everyone, regardless of their genitalia.

It’s impressive that the film is so self-aware, even postmodern, despite there having been only four ‘official’ cinematic adventures released at this point. Then again, the pre-eminence of Bond’s penis had already been well established in the Eon films; it has already caused a Russian patriot to defect in From Russia With Love, converted a lesbian in Goldfinger and inspired Thunderball’s Fiona Volpe to launch into an almost-fourth-wall-breaking speech, excoriating Bond about his overreliance on his bedroom prowess to get the mission done: “I forgot your ego, Mr. Bond. James Bond, the one where he has to make love to a woman, and she starts to hear heavenly choirs singing. She repents, and turns to the side of right and virtue... but not this one!"

The ‘real’ Sir James Bond is keeping it in his trousers, much to the annoyance of SMERSH. It only becomes clear (and then murkily so) in the very late stages of the film (see Villains, below), why they are hell-bent on testing the limits of Sir’s “moral vows”. Even if we were given a stronger motivation, the lengths that SMERSH go to in order to destroy his “image” would still be parodically over the top. Although having said that, the plot hatched by SMERSH in the novel of From Russia, With Love (SPECTRE in the Eon film) is not exactly down-to-earth.

From Russia With Love revolves around a honeytrap too, a tool in the spying community’s aresenal that had a plethora of queer resonances. And Casino Royale features a scene in which compromising photos are being auctioned to rival powers. I explored real life agents being photographed with their pants down - particularly queer agents - in my queer re-view of From Russia With Love. For gay male civil servants in particular, the 1950s and 1960s were fraught with peril. How would one possibly know that the person buying you a drink in a bar wasn’t doing it under orders from the KGB?

When Agent Mimi, posing as M’s widow, asks Sir James to “doudle me”, as is apparently the custom following the death of the laird, Bond pours cold water on her ardour by paraphrasing Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “A quaint custom, but one more honoured in the breach than in the observance.” His refusal to sleep with her means he must “pay the piper” by competing in a ‘warsaling’ contest. The physically slight Bond must compete with burly, kilt-wearing, red-haired henchmen to heft some very weighty concrete balls. The sexual connotations are heightened by Sir James telling everyone that “I haven't warsled for years. I may be a little out of p-practice.”

Although Casino Royale does not present Sir James’s stutter (or anything) consistently, it becomes more noticeable in any scene where any form of sexual activity - literal or sublimated - might be on the cards. When he finds a naked seventeen year old (named Buttercup) in his bathtub, eager to scrub his back: “You're sure I'm not c-crowding you?” Incidentally, Buttercup was played by Angela Scoular who would turn up two years later in Eon’s OHMSS in a similar role, tempting Bond who is posing as the gay-coded Sir Hilary Bray (“Oooh you are funny, pretending not to like girls.”). Things take a potentially incestuous turn when Buttercup she announces she used to do the same for her daddy. At this point, Bond doesn’t know that the whole of M’s castle has been taken over by SMERSH agents, so who knows what he might be thinking about his deceased boss. And it’s here that his stutter returns: “I am not your d-da... Quite.”

Speech and Language Therapy expert Jill Douglass has observed that the social stigma attached to stuttering means those who do stutter often remain ‘in the closet’ and try to ‘pass’ as non-stutterers. It’s an under-researched field and Douglass argues that relating the experiences of queer people to those of stutterers may help to broaden understanding of what people who stutter go through. Of course, many people are both queer and have stutters. There is a online group for queer people who stutter and their allies called ‘Passing Twice’. Riley McGuire, an academic working at the intersection of queer and disability studies has explored how, in the 19th Century, overcoming a stutterr was sometimes seen as analogous to - and even synonymous with - overcoming same sex attraction. And James Thomas Haley has explored how, despite men being several times more likely to stutter than women, speech disfluency is often seen as a weakness, and therefore a threat to their masculinity.

Sir James feels self-conscious about his “stammer”, which clears up when he starts resuming his work for Her Majesty’s Secret Service, suggesting that he felt less of a man because of his dereliction of duty towards queen and country, rather than any perceived sexual inadequacy. Getting back to work also seems to awaken his libido. Now in charge of the Secret Service, Sir James takes a prurient interest in Vesper’s naked form when he calls her as she’s bathing.

Bond 3: Moneypenny

Technically, she’s Moneypenny’s daughter. She tells Sir James that her mother “took the vows” after he left the Secret Service (the implications of so many women in Bond’s life becoming nuns is explored below, under Girls).

Moneypenny in this film has far more agency than her counterpart in the Eon films, at least until very recently. As Lotte points out: “Moneypenny is in on the action long before Naomie Harris's time.”

The Moneypenny played by Barbara Bouchet is charged with finding “the one man all women want” and has the onerous task of trying them all out. Although it does shut down some possibilities (some women don’t want a man of any description), it’s a tantalising role reversal with a line-up of men being subjected to the objectification usually reserved for women.

Bond 4: Coop

Being a holder of the “Kama Sutra black belt”, Cooper is positioned as the ultimate ladies man. Even his name, as Moneypenny observes, suggests something “for keeping birds”. He’s the most conventional-looking of the Bonds for anyone familiar with the Eon films, which makes it all the more fitting that he’s having his sexual programming re-written.

In a wonderfully perverse scene, Cooper, is trained to “ignore” the appeals of a room full of attractive young ladies. He’s no longer merely Cooper/James Bond 007, but the Secret Service’s AFSD (Anti-Female-Spy-Device). He protests that “it goes against my nature” to rebuff the beauties and ends by announcing he’s going to get his “head examined”.

On my recent re-viewing, I recalled this scene more clearly than most of the others, indicating it was something I ruminated on through childhood and my teenage years. Whereas most of the film had been reduced to a technicolour haze in my memory, I could recall almost every shot and line of dialogue in this scene.

Perhaps it was because it showed someone wrestling with their true “nature”. Yes, it’s a straight man resisting women but it doesn’t take much imagination for a queer person to project themselves onto Cooper. The scene could even be taken as depicting some form of conversion therapy, something which is still disturbingly prevalent around the world.

Cooper’s allusion to requiring psychiatry would also resonante with any queer person thinking there was something wrong with them. Same sex attraction was still considered a mental illness in the USA and UK at the time of Casino Royale’s release, for both men and women.

Cooper being conditioned to resist women doesn’t necessarily shut down other possibilities of course. Many of the real life high-profile victims of honeytraps were men who had been caught in flagrante with other men. Perhaps he should have been trained to be an Anti-Anyone-Spy-Device.

Bond 5: Vesper

When we first meet Vesper she’s ordering men around, running her vast business/crime empire and negotiating the transportation of Nelson’s column so it can be situated, for her sole viewing pleasure, outside the window of her luxurious, multi-levelled Mayfair apartment. Like many male Bond villains in the Eon series (Dr. No and Goldfinger especially), her environment and speech reveal her to be an unapologetic materialistic, perhaps implying that her particular perversion is object sexuality.

The masculine-behaving but feminine-looking Miss Lynd claims to be purely mercenary (“I save all my energies for business”) and only does Sir James’s bidding, including seducing Evelyn Tremble, because he threatens her with a massive tax bill. As in the Eon series, the music is instrumental in bringing some romance to what might otherwise be a solely transactional sexual encounter. This time, song-writing legends Burt Bacharach and Hal David provide a song to rival Barry’s: The Look of Love, performed by lesbian chanteuse Dusty Springfield. It also appeared three years later on the soundtrack to the first filmed version of gay play The Boys In The Band.

In a brilliant essay, Robert Von Dassanowsky persuasively argues that Vesper represents “a major rupture in the conception of the Bond myth as it applies to women and sexuality”. She is the dominant one who breathes life into Bond, moulding an Alpha male out of feminised Tremble-shaped clay. When she ends his life, the unconventionality of her character is underscored by her clothing: she is dressed in male drag, as a bagpiper. In Von Dassanowsky’s view, this further destabilises “the traditional heterosexual dyad”.

Like the Vesper of the Fleming novel and 2006 film, Vesper ultimately turns out to be a traitor, who has been working for her own interests all along. But could you blame her really, considering how she was coerced into serving as another ‘James Bond 007’ as part of Sir James’s madcap scheme? In the casino-set finale, she tells Sir James she “went through a lot of trouble to bring you here”, although the scenes which showed this were probably left on the cutting room floor. Mysteriously, she says that “This time” she’s doing what(ever?) she’s doing “for love”, hinting that a redemption arc for her character existed at one point. Even so, she’s not all bad: she ends up in heaven with most of the other Bonds.

Bond 6: The Detainer

Like most of the other James Bonds in Casino Royale, The Detainer puts her sex in service to Her Majesty. Firstly, she is the girl who Coop (see above) finds most alluring during his Anti-Female-Spy-Device training. When Coop asks what she does, she replies, confident in her abilities to cause a reaction in (almost) any man: “I don't do anything. But unless you're one of them, you do.” The them is, of course, a euphemism for a gay man. Maybe this is another reason why this scene is etched into my memory.

At the end, two years before Tracy does the same in the Eon series, The Detainer helps to foil the villain’s scheme by flattering to deceive, making him lower his defences. A female James Bond with agency, way ahead of her time. True, by getting the villain to ingest his exploding pill, she dooms everyone in the casino as well as the villain, but in her brief screen time she makes a striking impression, whatever one’s sexual orientation.

Bond 7: Mata Bond

With the addition of both Moneypenny’s and Bond’s daughters, the Secret Service is, by this point, a family business. I have explored the importance of family in Bond before: for a character who is often portrayed as a loner he has a considerable support network, something many queer people might relate to. But thus far at least, Mata Bond is the only cinematic depiction of a Bond blood relation.

Or is she?

Sir James tells his assistant Hadley that he is the “sort of godfather” to Mata. But in the next scene he tells Mata herself that she is his “child”. Sir James appears to be ashamed to admit to Hadley that his romance with Mata Hari resulted in an “illegitimate” child. Perhaps the filmmakers kept the nature of Sir James’s/Mata Bond’s relationships purposely ambiguous, especially because the ages don’t match up (Mata Hari died in real life 50 years before this film is set). Even so, the prevailing view of the film’s fans is that Mata is Sir James’s daughter, which makes it a little uncomfortable when she tells him “if you weren’t my dad I could fancy you”, quickly followed by Sir James’s remarking about the size of her “equipment”, which, he tells her, are much bigger than her mother’s. Furthermore, she tells her father that she is “the Celestial Virgin of the Sacred Altar” and he questions whether she means it literally or figuratively. Virginity has a strange status in the ‘official’ Eon Bond movies, particularly in Live and Let Die, personified in the figure of Solitaire. Curiously, Mata and Solitaire are both introduced in similarly ornate, ceremonial clothing, as if they are living statues, perhaps signifying their on-a-pedestal status and unattainability.

Mata responds to her father “of course”, implying she is very sexually experienced. But this is Casino Royale, so don’t get hung up on consistency. Later, when she pulls on a toilet chain to spin it around, revealing a secret room, she announces that “it’s the first john I’ve ever gone ‘round with”. We should probably treat the use of “john” (slang for toilet as well as a prostitute’s client) as merely a throwaway gag. We could read into it that Mata is, relatively-speaking, sexually conservative. But like her father and mother, she’s not averse to using her “equipment” to seduce enemy agents. Essentially, like them, she’s a prostitute for her country.

For me, the shadow of Marlene Dietrich hangs over the whole Berlin sequence. She’s who I think of whenever someone mentions Mata Hari. When Mata arrives at the Checkpoint Charlie, there are neon signs for a club called the Blaue Engel, a reference to the Dietrich-starring film of the same name, directed by Josef von Sternberg. A year after The Blue Angel, they re-teamed for Dishonored, the story of a female spy who is ultimately led to a firing squad. Dietrich’s character was explicitly based on the real Mata Hari. Von Sternberg’s films often revolve around characters torn between love and sacrifice for a cause, especially those he made with bisexual Dietrich, who herself was torn between her public movie star persona and her private life.

Similarly, as ‘swinging’ as Mata Bond often is, she sometimes uses archaic words and phrases (the finishing school’s influence?) while maintaining an otherwise late-60s diction (“the Prime Minister really “turns me on”). This includes when she announces, as they try to escape Dr Noah’s base: “I say! Super place for a coming-out party.” Is she using this with the early 20th meaning attached to debutante balls, or the more recent sense, albeit one that had been used by some subcultures since the 1930s, of revealing one’s queer self? Amid the colourful, hedonistic chaos of Casino Royale, you could argue for either. Furthermore, Mata’s introductory scene is peppered with thinly-veiled drugs references (hookah smoking, poppy seed tea). Sex, drugs and Casino Royale?

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

Like most of the characters in Casino Royale, M’s identity is unstable. Following M’s death (by accident, at his own hand) Sir James Bond visits his ancestral home. Except for the pipers (who don’t count, for reasons unexplained) the household is made up exclusively of women (“My daddy only liked the lassies”) leading Sir James to conclude McTarry (his real surname) was “a different man in Whitehall”. Except, the McTarry household has been replaced by SMERSH agents. Except the chief agent later adopts the McTarry name after revealing her ‘true’ identity (see Mimi, in Girls below). It’s all deliriously confusing.

In a film where identities are constantly shifting and inconsistent, it’s entirely appropriate that Mathis switches from a British accent, to a French accent and finally to a Scottish accent for no apparent reason.

Q is almost as irascible as the Eon Q, giving Tremble a withering response when he attempts to make a gag about “poison pen letters” (which is actually recycled, without irony, in 1983’s Octopussy).

Q’s assistant, Fordyce, played by John Wells, who would go on to impersonate Margaret Thatcher’s husband at the end of Eon’s For Your Eyes Only, is a camp homosexual caricature. Queer critic Vito Russo would have Fordyce termed a ‘sissy’, an archetype dating back to the early days of cinema. Sissies were ‘safe’ because they were desexualised. The film of Russo’s famous book, The Celluloid Closet, observes that the sissy “made everyone feel more manly or more womanly by occupying the space in between.” And that’s what Fordyce does in Casino Royale. He’s there to aid Tremble’s transition to the macho James Bond figure by appearing effeminate alongside someone who, mere scenes before, was camping it up himself. The intent is signalled at the very start of the scene, with Q introducing Tremble to Fordyce as the “new man”. Contemporaneously with Casino Royale, the Carry On films had presented a plethora of sissy characters, most commonly performed by Charles Hawtrey. If anyone is in any doubt about which way Fordyce swings, those doubts are banished when he asks Tremble “which side do you dress, sir?” as he measures him up. Some gay men find the sissy stereotype offensive whereas others relish this earlier form of representation. I’m somewhere in the middle.

Shady characters: Villains

Does height really matter?

For Jimmy Bond (aka Dr Noah) it’s everything.

The whole film turns out to be motivated by his plot to kill off tall men, eliminating the competition. In Jimmy’s own words, he dreams of a world where “a man, no matter how short, can score with a top broad”. Jimmy’s feeling of sexual inferiority is something the film has the courage to state explicitly whereas an Eon production would mask it in euphemism and symbolism. As Sir James summarises: “All this just to make up for your feeling of sexual inferiority? I'm beginning to think you're a trifle neurotic.”

So-called ‘short man syndrome’ is likely to be a result of social conditioning, perhaps based on some kind of perceived evolutionary advantage (tall man = better hunter?), reinforced through media imagery.

And heterosexuals say that queer people are complicated!

A 2015 survey of a large number of non-heterosexual men found that, when it came to preferred height of partners, there was a bias along conventional gender roles: “Men that preferred a more dominant and more “active” sexual role preferred shorter partners, whereas those that preferred a more submissive and more “passive” sexual role preferred taller partners.” Although the researchers were eager to point out that “a large proportion of men preferred to be in an egalitarian relationship” and it was not as simple as it might first appear: “Our results indicate that preferences for relative height in homosexual men are modulated by own height, preferred dominance and sex role, and do not simply resemble those of heterosexual women or men.”

In other words, if only Jimmy were gay, he might not be so fixated on his height and its attendant feelings of inferiority. In contrast with Jimmy, the heroic Tremble is depicted as tall. Although the two characters never appear on screen together, this is made explicit by Sellers impersonating two real famous short people: Napoleon and Toulouse-Lautrec.

Like his uncle James, Jimmy Bond (aka Dr Noah) suffers from a psychological speech disorder - a manifestation of his feelings of inferiority. But rather than merely stuttering like Sir James, he is incapable of saying anything at all around his dominant uncle.

Despite his limited screentime, Jimmy reveals a lot about his sex life. One of his kinks is undressing and tying up women, something he says he “learned in the Boy Scouts” (another gag partly recycled from What’s New Pussycat?). And he is proud to say he has had “profoundly moving religious experiences” with at least one of his doubles (the one that mimics The Detainer).

In comparison, we learn little of Le Chiffre’s sexuality. Perhaps if we had a version of the infamous homoerotic carpet-beater scene (from the novel and 2006 Casino Royale film), things might have been different. This element did appear in an early draft but was scrapped. Instead, we have Tremble tied to a chair and a form of psychological punishment (“The most exquisite torture is all in the mind”). The torture Le Chiffre chooses for Tremble involves him being presented with a pageant-full of beautiful girls and being expected to choose the winner. Is this torture because he could not possibly choose as they’re all equally beautiful, an even-more-twisted mirror image of the scene we saw earlier with Coop having to fight his programming and refuse a line-up of women? This reveals more about Tremble, surely, than Le Chiffre. Or, more accurately, reveals the filmmakers finding another excuse to cram more aesthetically pleasing young ladies into an already overstuffed film.Le Chiffre himself is constantly flanked by beautiful ladies around the casino table, although they seem to be there more for the audience’s gaze than Le Chiffre’s.

In fact, the only think we learn about Le Chiffre’s sex life is his enthusiasm for blackmailing governments using pornographic photographs. Is he a voyeur?

As with Woody Allen’s height-obsessed Jimmy Bond, it’s difficult to separate Le Chiffre from what we know of the real-life Orson Welles. According to Welles’s biographer, Simon Callow, the legendary film director and actor was “in the grip of a peculiary perverse compulsion”, with his three marriages “scuppered from the beginning by his sexual restlessness”. While there was never a hint of any same sex activity, it’s hardly heteronormative to marry Rita Hayworth one week and cheat on her the week afterwards.

Welles is photographed sitting down in Casino Royale, in part due to his bulk (his appetite for food matched that of his appetite for women). But it may also be due to his height. Like the Jimmy Bond character, the real-life Orson Welles was very insecure about his height. Despite being 6 feet tall, he often resorted to platform shoes to make himself tower over others.

Although Welles never made a film where homosexuality was a central concern, he did appear in 1959’s Compulsion as the lawyer defending the real life gay murderers also depicted in Alfted Hitchcock’s queer classic Rope. And in his own work behind the camera, critics have identified that his films usually eschew heteronormativity and notable queer filmmakers, such as Gus Van Sant and Todd Haynes, have been influenced by Welles.

Frau Hoffner looks like she has just stepped off the set of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the queer German Expressionist masterpiece. Anna Quayle’s line delivery is delectable (“Vewy democratic”) and, for me, this exchange with Mata encapsulates the bizarre, contradictory logic of the film.

Hoffner: Who said anything about an auction?

Mata: You did.

Hoffner: Who am l?

Mata: Frau Hoffner.

Hoffner: Never heard of her. You're insane. Quite insane.

Mata: I think she's right.

When femme fatale Miss Goodthighs slips a sleeping tablet into Tremble’s Champagne she sets up one of the best gags in the film, with a prematurely tipsy Tremble declaring “My goodness this is strong shampoo”. Although Goodthighs fits into the Bond tradition of objectifying women by naming them after parts of their bodies, the usual possibilities are shut down almost immediately by Tremble complaining about her lying on his “loose change”. Before he passes out, he tells Goodthighs she should start without him.

You go gurls!

After all the female James Bonds (above), Mimi’s really the only girl left of note. And what a girl! Before we meet her we learn from the other SMERSH agents that “Mimi’s never failed yet.” So why didn’t I include her in the Villains category? Well, she’s the girl who, to go back to Fiona Volpe’s words, “repents, and turns to the side of right and virtue”. And this time, his penis has nothing to do with it. Except it has everything to do with it. Sir James’s prowess with heavy stone balls is enough to have Mimi hearing the “heavenly choirs singing”. Perhaps because he refused to do more (and “doudle” her), Mimi is converted to the cause. Later in the film, she reappears as a nun. Like Moneypenny, she has also sought a life of celibacy, presumably because she can’t have Bond and doesn’t want to settle for second best.

It’s a disturbing convention of Western fiction that a woman spurned by ‘the one’ man should be compelled, like Ophelia in Hamlet (a play invoked in Casino Royale) to “get thee to a nunnery”. Mimi actress Deborah Kerr famously played another nun in another study of sexual repression, more critically acclaimed than Casino Royale: the Powell and Pressburger masterpiece Black Narcissus. The 2020 remake of Black Narcissus starred Bond girls Gemma Arterton and Diana Rigg, accidentally suggesting that, after Bond, a woman can’t do any better so she may as well cut herself off from the sexual life. Although in Arterton’s and Rigg’s cases, their Bond girl characters end up dead, which is not much of an alternative.

Prior to her trip to a priory, Mimi spins a (presumably fictionalised?) yarn to Sir James of the McTarry clan that M belonged to. It’s a torrid family tale of repeated rapes which is only saved from being utterly horrifying by it being almost nonsensical.

Redeemed, Mimi asks Sir James to “Think of me as the second woman in your life. The one after Mata Hari.” When she reappears, it’s as Sister McTarry. Is this a pseudonym or was she M’s widow, Lady Fiona, after all?!? The filmmakers seem to have lost track as well because Kerr is credited as “Mimi (alias Lady Fiona)” on the closing titles. Mimi/Sister McTarry/Lady Fiona/whoever appears in the Secret Service headquarters to inform Sir James where Mata is being held captive. There’s a hint of her affection being reciprocated but, in common with the Eon series of films, we know James Bond will never settle down with a woman.

The Bond films are no stranger to drag, especially when it comes to stuntmen playing women. In the sequence where Mimi climbs down the drainpipe she is played by stunt artist Roy Scammell.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

Whatever you may feel about the film’s story and characters, in terms of style, Casino Royale outstrips the Eon series several times over. And that’s saying something when the Eon films are some of the most well-designed, aurally-pleasurable films of all time. I’ve referenced Susan Sontag’s seminal essay ‘Notes on Camp’ before but it’s rarely been as relevant as it is here: “To emphasize style is to slight content, or to introduce an attitude which is neutral with respect to content.” Casino Royale frequently slips into a purely aesthetic mode - I.E. what is on screen is not in service to the story; it’s just there to look or sound good. This is most explicit in the sequence introducing Mata Hari, which is like something out of an MGM musical (and, in all honesty, a bit tiresome), but the set design, costumes, music and cinematography are marvellous throughout. Casino Royale is a lot easier to enjoy if you approach it from an aesthetic point of view.

If that doesn’t float your boat, then you could approach it as a drinking game. If we’re being generous to the Eon films, we could say Casino Royale ANTICIPATES or even INSPIRES some of the later ‘official’ Bond films. If we’re not being generous we could say that Eon STOLE liberally from Casino Royale. Of course, it’s entirely possible that creative minds thought alike. Whatever happened, you can have great fun watching Casino Royale spotting all the bits which appear in later Bonds. Just be careful though, if you do decide to drink whenever an ‘Eon moment’ pops up, do be careful and choose something with a fairly low ABV: there are a LOT of such moments! Some of my favourites to look out for include: exploding cigarettes (You Only Live Twice, the Eon film being shot at the same time as Casino Royale); the ‘Angels of Death’ in M’s castle, like those at Piz Gloria, even down to the under-the-table and under Bond’s kilt action (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service); doubles/clones and the shots through the fish tank (Diamonds Are Forever); the giant overhead magnet used to combat an adversary (The Spy Who Loved Me); the grouse shoot (Moonraker); the dodgy French car wash (A View To A Kill); the infrared/x-ray glasses (The World Is Not Enough); the villain being revealed to be a relation of Bond’s and taunting him from the other side of a glass screen (Spectre).

Despite being a ‘parody’, Casino Royale features few direct references to the Eon Bond films which came before it. Like the best parodies, it distills the essence of its subject. An obvious exception is the Goldfinger pastiche in the finale where a mirror is smashed to reveal a secret room where girls are being painted gold.

The film abounds with other intertextual references. When M’s car drives through Bond’s estate with a lion on the roof we get a blast of John Barry’s Oscar-winning score to Born Free. And Secret Service taxi driver Carlton Towers’s (Bernard Cribbins) opening a drain cover so he and Mata can escape Berlin triggers the famous theme song to What’s New Pussycat? (see discussion of this film in the Bond section, above).

When Le Chiffre is killed, there is a literal presentation of breaking the fourth wall when his assassins smash through the monitor he was watching them through only moments before.

In fact, there is so much fourth wall breaking in this film that this article would be double the length if I was to list everything. But a particularly notable instance is when Frau Hoffner tells Mata that “Some of the greatest spies in the world have graduated from this institution: Von Grudendorf, Malenvosky…” Robotic manservant Polo (Ronnie Corbett) finishes her list: “Peter Lorre, Bela Lugosi.” Bela Lugosi was never, as far as we know, a spy but instead the actor most famous for playing Dracula. Whereas Peter Lorre played Le Chiffre in the 1954 TV adaptation of Casino Royale. Another great reference is when Sellers screams an animated HELP, a la The Beatles (who are also name-checked in the film’s opening shot).

There are countless cameos but, to my gay male gaze, the rather attractive John Paul Belmondo stands out. The French movie star is name-checked in a song from gay-themed play La Cage Aux Folles. In ‘Masculinity’, an effeminate gay character is told to butch it up by thinking of “John Wayne and John Paul Belmondo”. At the time he filmed his cameo as the French Legionnaire in the finale, Belmondo was in a relationship with Ursula Andress. Lucky Ursula.

Fans of innuendo may delight in the car chase as the SMERSH agents chase Sir James’s Bentley with a radio-controlled milk truck. “Prepare to deliver milk” the announcer intones shortly before everything ends in an explosive mess. Come to think of it, this isn’t the last time in the Bond films that a milk truck is used to queerly menacing effect. See also Necros in The Living Daylights. It is the first time that a villainous organisation uses Scalextric to track Bond’s movements however.

This film’s hot Bond boys with bit parts have to be the red-headed pipers in kilts, especially the three introduced as Robin, Jock and Sandy. And in case you are wondering if they are attired like true Scotsmen, wonder no longer as I have painstakingly paused each frame of the sequences where they fall over unconscious and you do get brief glimpses of their underwear. Sorry to disappoint anyone.

Although the rainbow flag hadn’t been invented yet and was therefore not yet synonymous with the queer community, there are some rainbow-coloured cocks in Vesper’s apartment.

When gay stereotype Fordyce responds to Q’s admonishment that he has Tremble’s TV watch on the wrong channel he quotes the famously queer closing line from Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot: “Nobody’s perfect”. Wilder himself was involved in the writing of Casino Royale although it’s believed little, if any, of his contribution made the final cut.

The hilariously indecisive British army officer at Le Chiffre’s pornography auction is played by Richard Wattis who is probably most familiar to British viewers for playing uptight civil servants throughout the 1950s and 1960s and a stuck-up neighbour in a 1970s sitcom. Wattis was gay and was born in the town where I now live, Wednesbury. There’s even a street named after him several streets over from my own.

In the final, climactic cacophony, Peter O’Toole, star of Lawrence of Arabia and What’s New Pussycat?, appears blowing some bagpipes before asking if Tremble/Peter Sellers is Richard Burton to which Tremble/Peter Sellers replies he’s Peter O’Toole. All of this is a reference to Burton’s cameo in What’s New Pussycat? but if you’ve not seen that film it appears to happen for no reason. Anyway, the important thing is Peter Sellers pulls seductively on Peter O’Toole’s sporran. This also happens for no reason. Are we having fun yet?!!?

Seven James Bonds at Casino Royale,

They came to save the world and win a gal at Casino Royale.

Six of them went to a heavenly spot,

The seventh one is going to a place where it’s terribly hot.

Singer Mike Redway was asked to perform the first verse of this end titles song, and the song that appears in the torture sequence, in the style of Noel Coward, one of Ian Fleming’s famous gay friends. Leaving aside the lyrics’ mathematical error (it’s eight James Bonds if you count Jimmy among them, which the song does), Seven Bonds In Heaven (Have No Fear - James Bond Is Here), makes it clear that “they” came to “win a gal”, heedless of their gender. Four of the Bonds are women so if we’re to take this literally, the majority of the James Bonds are lesbian or bisexual. Have no fear - the queers are here! Hooray!

Double 0h-Just-Give-In-And-Enjoy-Yourself out of 007

Casino Royale’s fractured narrative presents us with an alternative world where boundaries are more permeable or entirely non-existent: nationalities, names, accents, genders and sexual orientations are all less clearly defined than Bond fans are accustomed to. Whether you’ve joined the Casino Royale ‘fun movement’ already or you’re still resisting its call, it will be there waiting for you when you’re ready.