What makes you think this is the first time?: assumption, possibility, and bisexuality in Bond

‘What makes you think this is my first time?’ Bond asks Silva, who’s got him tied to a chair and is running his hands up his thighs. And a legion of queer Bond fans cheers – quietly, so as not to disturb the rest of the cinema. Let’s be real: Silva wasn’t the only one who assumed that this was the first time. Kathleen Jowitt explores Bond’s bisexuality.

My experience as a bisexual woman has always been shaded with other people’s assumptions. That my existence in an LGBT space can only mean that I’m gay. That an eleven year long marriage to a man makes me straight. Infuriating as it is, I can see how it happens. People work with what they do know, and guess at what they don’t. We’re human. We all extrapolate from incomplete data: we’d never get anything done if we didn’t. And there’s nothing wrong with that – provided that we always remember that that’s what we’re doing. That we might be wrong.

Assumptions are dangerous, particularly in a franchise that relies heavily on suspense, misdirection, and twists. Assuming that what you see on the surface is all there is to see leaves you vulnerable. Assuming that an apparent ally can be trusted might get you killed.

The audience can get caught out, too. We think we know how this goes. We think, ah, M will survive this: she always does. And then Skyfall happens. Or we get to the last chapter of From Russia With Love and discover that Bond himself isn’t immune to a poisonous blade concealed in a shoe. Or, on a lighter note, there’s that glorious bait-and-switch at the opening of The Spy Who Loved Me, where Agent XXX turns out not to be the hairy-chested hunk, but the beautiful woman he’s in bed with.

We rely too heavily on the data we do have, and dismiss the data we haven’t yet come across. What made us think it was the first time? The answer’s obvious: nearly seventy years, first in the books, then in the films, of James Bond the womaniser. We assumed, based on what we saw. Sometimes we saw something and dismissed it. Indeed, many viewers will have been tempted to dismiss that ‘first time’ line: he’s bluffing; he’s trying to wind Silva up; you’d admit to anything under torture.

But Bond was always a man with a history – perhaps several histories – that we never knew. In the books, there was his war service, often mentioned in passing, but never really explored. In the films, it’s more fluid. In For Your Eyes Only we see Bond laying flowers on his wife’s grave; very touching, but we hadn’t heard a word of her in the previous five films. ‘Old acquaintances’ turn up who we’ve never heard of before – Valentin Zukovsky, for example, or Paris Carver. Casino Royale is, of course, a clean start, taking us back to the beginning – but of course it isn’t. It’s informed by all the films we watched before.

There’s an awful lot of James Bond that we don’t know. So what made us think it was the first time?

Possibility

Here’s Bond preparing to play roulette in the novel of Casino Royale:

“Bond borrowed the chef’s card and studied the run of the ball since the session had started at three o’clock that afternoon. He always did this although he knew that each turn of the wheel, each fall of the ball into a numbered slot, has absolutely no connexion with its predecessor. He accepted that the game begins afresh each time the croupier picks up the ivory ball with his right hand, gives one of the four spokes of the wheel a controlled twist clockwise with the same hand, and, with a third motion, also with the right hand, flicks the ball round the outer rim of the wheel anticlockwise, against the spin.

“It was obvious that all this ritual and all the mechanical minutiae of the wheel, of the numbered slots and the cylinder, had been devised and perfected over the years so that neither the skill of the croupier nor any bias in the wheel could affect the fall of the ball. And yet it is a convention among roulette players, and Bond rigidly adhered to it, to take careful note of the past history of each session and to be guided by any peculiarities in the run of the wheel. To note, for instance, and consider significant, sequences of more than two on a single number or of more than four at the other chances down to evens.”

We respect the history. Of course we do. But we have to remember that history won’t necessarily repeat itself.

The other side of assumption is possibility. When we leap to one particular assumption, we ignore all the other things that might equally well be true. Throwing the light on one possibility puts hundreds of others into the shade. And my experience of being bisexual has been the ever-present consciousness of other possibilities. I’ve made a particular series of choices, my life has unfolded in a particular way – but I’m always aware that I could have made other choices, that my life might look very different today if... If I hadn’t grown up under Section 28. If I’d heard the word ‘bisexual’ before the age of 20. If, if, if. Well, we could look into alternate universes forever, and I’m happy enough with the way that things have turned out for me.

In the Bond universe, as I’ve already noted, the stakes are higher. The genre-savvy viewer, reader, or, indeed, character, will trust no one. Anyone can betray you. A sexual partner can betray you. It’s tempting to close that circle and conclude that anyone can be a sexual partner.

Certainly anyone can die. The universe in which James Bond operates is, despite the glitz and glamour, a gloomy one, where sex and death are closely linked. So many of Bond’s sexual partners are killed, and it’s often as a direct or indirect result of their contact with him. But then so many of Bond’s associates are killed, and often for the same reason.

In the novel of Goldfinger, as in the film, Tilly is killed by Oddjob’s bowler hat. But the difference in the book is that she’s struck down as she runs, seeking protection with Pussy Galore. Bond takes it personally. ‘I could have got her away if she’d only followed me,’ he tells Felix. But he seems to have forgotten that earlier in the book choosing him over Goldfinger was equally fatal for her sister Jill.

Or consider the character of Xenia Onatopp, for whom sex and killing go together. She isn’t fussy about the gender of her victims, and seems to be able to get off no matter who she’s bumping off.

There’s some textual evidence of bisexuality in the novels, though I have to raise my eyebrows a little at passages like: “Rosa Klebb undoubtedly belonged to the rarest of all sexual types. She was a neuter. Kronsteen was convinced of it. The stories of men and, yes, of women, were too circumstantial to be doubted. She might enjoy the act physically, but the instrument was of no importance. For her, sex was nothing more than an itch.’ (From Russia With Love)

What about other possibilities? Well, the pervasive heteronormativity and monosexism of the society I’m writing in means that without concrete evidence the possibility of bisexuality is often dismissed, or, indeed, never thought of in the first place. If one raises it, one’s often held to an impossibly high burden of proof. So Bond’s extensive on-screen sexual experience with women is taken to negate the possibility of his ever being interested in anyone who isn’t a woman, and his response to Silva is dismissed as a joke. (And yet, here we all are, intrigued by the possibility of a queer reading of Bond!) “But which are you really?” Naysayers may demand equal quantities of equally satisfying activity with partners of both genders or it doesn’t count (the people who pull this guff don’t usually believe that non-binary people exist, either).

I’d argue that in actual fact we do get something like that over the first two books. Casino Royale presents us with two associates for Bond: Vesper Lynd and Felix Leiter. Both are strangers to him, and to the town; both have been sent to assist him in a mission that he was expecting to carry out alone. Each is given a detailed and attractive description. They stand together watching the baccarat game, watching Bond make his choices.

We leave Casino Royale with Vesper dead in a hotel room (“Only her black hair showed above the sheet and her body under the bedclothes was straight and moulded like a stone effigy on a tomb”).

Live and Let Die opens with Bond arriving in the USA and being checked into a very different hotel. And, waiting for him:

“The communicating door with the bedroom opened.

“‘Arranging the flowers by your bed. Part of the famous CIA “Service With a Smile”.’ The tall thin young man came forward with a wide grin, his hand outstretched, to where Bond stood rooted with astonishment.

“‘Felix Leiter! What the hell are you doing here?’ Bond grasped the hard hand and shook it warmly. ‘And what the hell are you doing in my bedroom, anyway? God! It’s good to see you. Why aren’t you in Paris? Don’t tell me they’ve put you on this job?’”

Indeed they have. And in the course of the novel Bond is decoyed twice over so that Felix can be kidnapped in exactly the same way that Solitaire was two chapters earlier. And there’s something very tender in the way that Bond watches over Felix when he’s returned, shark-mauled:

“He turned back to the body on the bed. He hardly dared touch it for fear that the tiny fluttering breath would suddenly cease. But he had to find out something. His fingers worked softly at the bandages on top of the head. Soon he uncovered some of the strands of hair. The hair was wet and he put his fingers to his mouth. There was a salt taste. He pulled out some strands of hair and looked closely at them. There could be no more doubt.

“He saw again the pale straw-coloured mop that used to hang down in disarray over the right eye, grey and humorous, and below it the wry, hawk-like face of the Texan with whom he had shared so many adventures. He thought of him for a moment, as he had been. Then he tucked the lock of hair back into the bandages and sat on the edge of the other bed and quietly watched over the body of his friend and wondered how much of it could be saved.”

I find it very striking how Felix is presented each time as a counterpoint to the female lead of the book. True, Bond ends up with the woman in each case. But Felix is the one who’ll show up in book after book.

He never does explain what he was doing in Bond’s bedroom. Who knows, maybe he really was arranging the flowers.

Married to the job: Bond, M, and loyalty

If we imagine James Bond as bisexual, it swiftly becomes apparent that he’d represent a collection of particularly offensive stereotypes of bi men: specifically, oversexed, unfaithful, and unreliable.

Except, that is, when it comes to the job. He’s very loyal to the job, and plenty of his antagonists give him stick about it.

Granted, he occasionally toys with the idea of quitting the job in favour of the woman he’s working with (or against). The narrative always intervenes, in the form of betrayal and/or death (or, in the book of Moonraker, the embarrassing fact that the woman in question really is engaged to somebody else). As the series progresses, this happens less and less often. The job wins.

But it’s not just the job. It’s a job that’s personified, at least in the books, as M. ‘The man who held a great deal of his affection and all his loyalty and obedience’ (Diamonds are Forever). Or (and this only a chapter after Bond has called to mind his disagreement with Troop over ‘intellectuals’ and homosexuals in the Secret Service) ‘the tranquil, lined sailor’s face that he loved, honoured and obeyed’ (From Russia With Love).

That’s an allusion to the marriage service in the Book of Common Prayer. Are we in Bond’s head here, or is this the narrator telling us how things are? Either way, Fleming is deliberately invoking a marriage here.

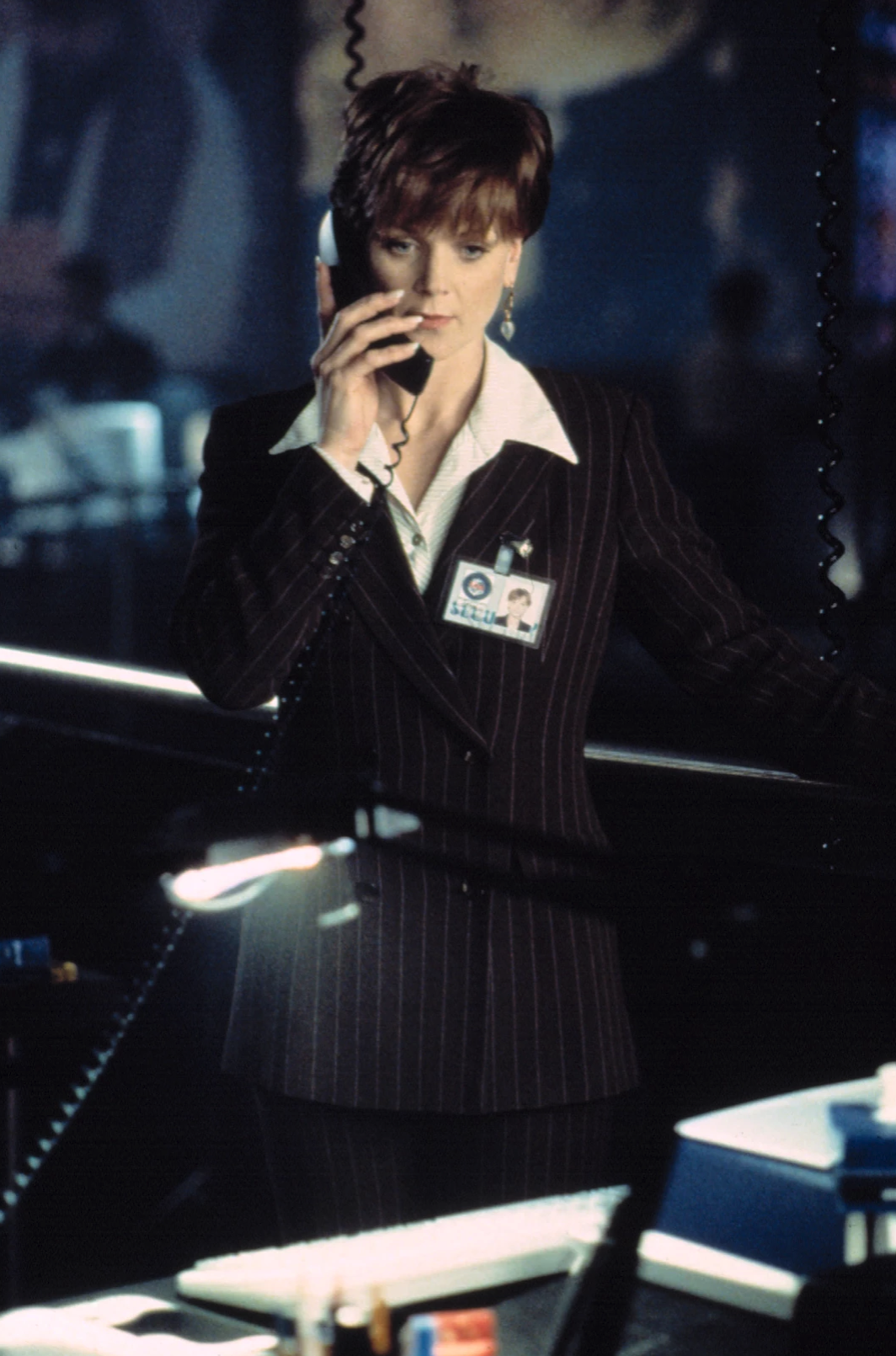

But more than that, it’s the bride’s line. Only the bride promises to obey. While of course this is literally true of the relationship between Bond and M (more true, one has to hope, than for the vast majority of the millions of women who have spoken and will speak the line in earnest), it’s a telling choice of phrasing. And, when the narrative also tells us that M disapproves of Bond’s ‘womanising’, it’s hard to deny that there’s a certain undercurrent. What happens to that undercurrent when the new M is, as Zukovsky puts it, ‘a lady’, is left as an exercise for the reader – but I’d say that their dynamic doesn’t really change all that much. Can I see Brosnan’s Bond, or Craig’s, promising to ‘love, honour, and obey’ Dench’s M? Yes, perhaps I could.

It’s interesting, too, that it’s a female M who’s the first to order Bond specifically to seduce a woman in the interest of a mission, making a straight assignment queer by proxy. (The situation in From Russia With Love is, I’d argue, rather different, since Tatiana makes the first move – though the scene in which she gets her orders has a similarly queer, and troubling, dynamic). ‘You’ll just have to decide how much pumping is necessary, James,’ observes Moneypenny, speaking for the audience, and making us complicit in the seduction.

The bisexual viewer

I started watching Bond films in my early teens. My first was A View To A Kill, or, at least, the second half of it. My second was The Living Daylights. My cousin and I, who were both learning to play the cello at the time, were more interested in whether the instrument was going to make it out in one piece than in anything else.

My brothers liked the films too. The collection of videos gradually increased. I learned a lot of Bond trivia (which I still remember) from a companion book (whose title I can’t remember). We argued over whether the fact that Xenia’s Ferrari had fake numberplates meant that it was a fake Ferrari and, if so, whether this was the reason that Bond could keep up with it in the beautiful but ageing Aston Martin.

I enjoyed the films for the jokes and the action. I enjoyed them for the cars and the clothes. I enjoyed how good everybody looked in evening dress – or an evening dress. I tended to find people attractive without necessarily being attracted to them. And there are an awful lot of attractive people in the Bond films.

When I thought about it, I assumed that I’d picked up what I’d later know to call a male gaze. Goodness knows there was a lot of it around. The book whose title I forget told me, ‘Sorry, Bond fans, this rare photo proves that Ursula was not naked during the radiation cleansing sequence!’ Which I always found a bit skeevy (and, apparently, memorable)...

It can be a confusing space to inhabit, identifying with both the seducer and the seduced, particularly when you don’t realise that’s what’s going on. As a young feminist, I was aware that both Bond’s behaviour and the way the narrative presented it were troubling. The scene in the stables with Pussy Galore in Goldfinger is an obvious example; personally, I find the coercion at the health farm in Thunderball even more difficult to watch. Men want to be him; women want to be loved by him? No. Not like that. At other times, when consent was enthusiastic and the experience was enjoyable, I could see the point. I was less troubled, if not less confused. And then there were things like the fight between the two girls in From Russia With Love...

At university, the Bond films were a welcome distraction from my degree. We were galloping through a thousand years of English literature in one module, and structuralism, postcolonial theory, feminist theory, queer theory, in the other.

It wouldn’t have occurred to me to apply any of that to James Bond. I wrote my dissertation on nineteenth century clergymen, real and fictional. Bond was for evenings with gin (we were ahead of the fad there) and ice cream and angsting to my friends. ‘My cousin thinks I might be a lesbian. I’m not sure he’s wrong. On the other hand, what about that gigantic crush we all know I have on that one guy...?’

But these were the days of LiveJournal, and those who worked through their emotions better in text than in speech had a forum in which to do so. We all wrote under pseudonyms, but we all knew who each other was, and we shared more in what was, generally speaking, a safe space. LiveJournal was where I met my first bisexuals – although in fact they were people I already knew. LiveJournal was where I first read the word ‘bisexual’. I remember filling in one of those long questionnaire memes, and hesitating for a long time over the statement ‘I am openly bisexual and have completely different reasons for being attracted to men and to women’. In fact, there were several different reasons why I couldn’t have answered ‘yes’ to that statement as a whole, but I still came away with a sense of not having been completely honest. It was about a year later that I claimed the word for myself.

Meanwhile, Bond moved on too. The old regime reached its gloriously cartoonish climax with Die Another Day. Daniel Craig took over from Pierce Brosnan, and we went back to the beginning, rediscovering the character, rewriting the history, returning to the point where a particular choice was made, exploring a whole, new, different set of possibilities, but always informed and influenced by the past.

Where am I now? I’ve returned to Bond as an adult with an expanded perspective. These days I enjoy all the things I used to enjoy without worrying whether or not I’m meant to be enjoying them. I still cringe at some bits – in fact, probably a few more than I used to. I find people attractive without necessarily being attracted to them. I still have my cello (very much not a Stradivarius), though it’s been a while since I took it out of its case.

And you know what they say: being bisexual means you never have to change the pronouns in the songs. And my goodness, the Bond franchise has some good ones.

Kathleen Jowitt is a trade union officer and novelist who writes contemporary literary fiction exploring themes of identity, redemption, integrity, and politics. She lives in Ely.

@KathleenJowitt