My video game crush on Xenia Onatopp

In this love letter to GoldenEye’s Xenia Onatopp, I explore what my obsession with playing as her in the classic Nintendo 64 version reveals about me, as well as what the research says about the choices we make in video games.

GoldenEye 007 game copyright Rare 1997

Those who struggle to see the value in video games might be surprised to learn that the industry as a whole is worth more than the movie industry. They would probably be even more surprised to hear that, because of its cultural value, gaming is the subject of a burgeoning field of academic research. One of the most fascinating avenues being explored is the relationship between human player and their in-game character, or ‘avatar’. Video games creators are eager to deepen this connection. The more people invest in a character, the more they are likely to play a game.

But that doesn’t mean the character has to be the same as the player. They may look different and sound different. They may be a different gender or sexual orientation.

You barely have to squint to see a similarity between some video games players and drag artists. Both play as ‘characters’, adopting personae different to their daily lives. Some games players may even prefer their lives online. They may feel truer to their other selves, just like many drag queens. An increasing number of video games present players with an almost unlimited range of options for customising their characters. Players can spend hours choosing attributes, from different skin tones to hairstyles to clothes. Undoubtedly, some people go for something not dissimilar from themselves, or even an idealised version. But more and more are choosing to explore alternatives. Video games developers are giving people more freedom to do so. Even Nintendo joined in with Mario Odyssey in 2017, allowing players to put their flagship mustachioed plumber character in a dress for the first time - a wedding dress no less, resplendent in blue pearl earrings and matching pendant necklace.

People who don’t play video games often see them as a waste of time. The reality is that video games are an art form like any other and worthy of critical study. Their culturally low esteem is merely a result of their being the ‘new kid on the block’, like cinema once was.

My own reluctance to spend much of my limited amount of free time on video games stems my own weakness. Apart from the odd indie title, I have rarely spent less than 100 hours on a game, especially if it’s ‘open world’. I get so absorbed by these virtual worlds that I spend hours just staring at the artfully rendered scenery. Once I take the plunge into one of these games, I find it hard to extract myself. It’s like an addiction.

I had no such issue giving in to my compulsions when I was younger however. I must have clocked up over a thousand hours on GoldenEye 007 on the Nintendo 64 from 1997. The single-player was compelling enough, but it was the split screen multiplayer (an alien concept to young people nowadays) which consumed whole days and weeks of our lives. My friends and I would even play it on our lunch break when we were in sixth form, walking a two mile round trip to my friend John’s grandad’s house just so we could squeeze in a quick game.

For 10 minutes each lunchtime, John’s grandad’s front room was filled with teenage boys competing to shoot each other in the head while also firing innuendo-laden insults at each other. It’s this sort of behaviour which gives video gaming its bad reputation.

But for us, it was glorious. Although some of my friends were sporty, we were never the ‘cool’ kids. While several of my friendship group would later come as gay, most of the GoldenEye 007 players were (and are, to the best of my knowledge) straight. Perhaps it is this that ostensibly hetero environment that influenced my choice of character.

One of the most appealing qualities of GoldenEye 007 was its huge choice of characters to play as. This is something commonplace to games nowadays. But in 1997 it was a novelty to be able to select from dozens of different characters, stand-ins for your real-life self. GoldenEye 007 even didn’t confine itself to Brosnan’s first Bond film either. It drew on the extensive back catalogue, especially the rogues gallery.

We only had one rule: no one could play as Oddjob.

Being shorter than the others meant he had a unfair advantage. Head shots would sail right over him.

Any other character was fair game though. Aside from the diminutive Oddjob, they were pretty much of a muchness, moving at the same speed, having the same accuracy and so forth. So it’s curious that I almost always chose the same one: Xenia Onatopp.

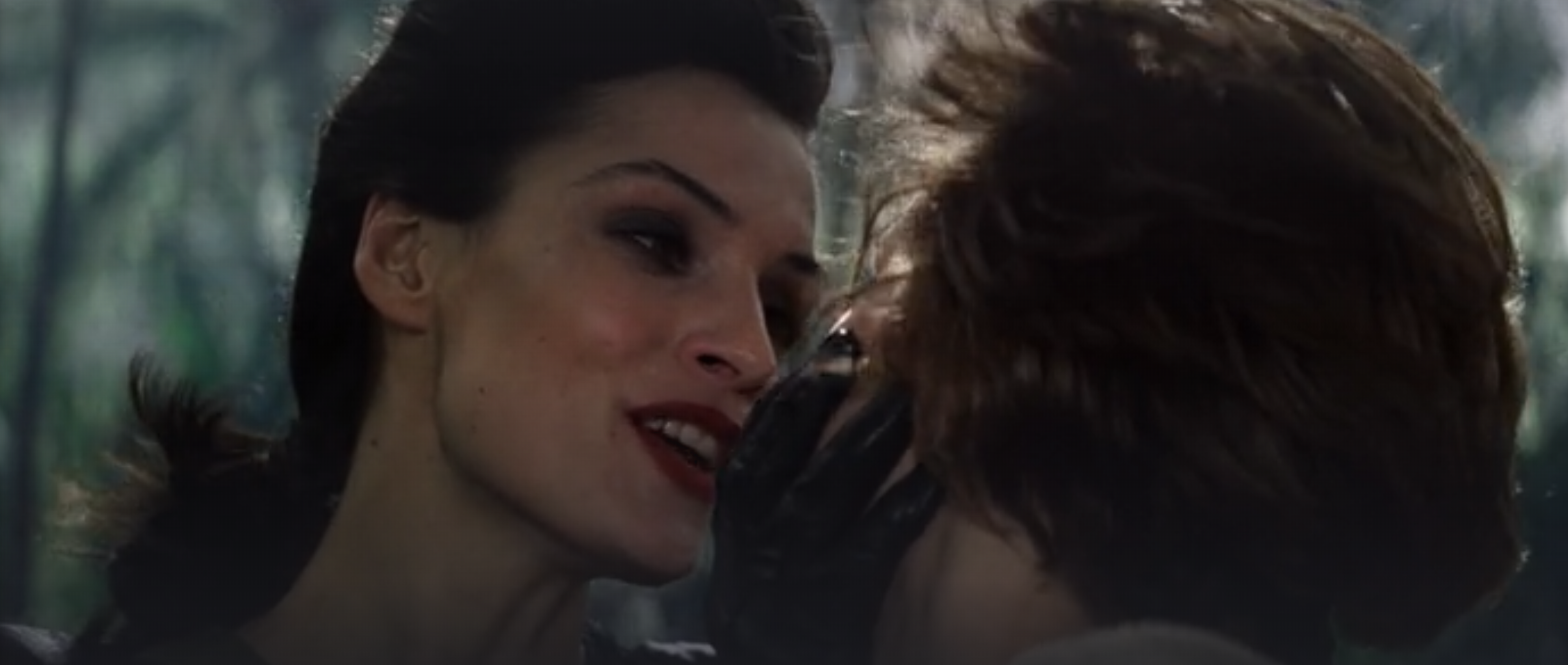

GoldenEye’s sadistic villainess derives sexual pleasure from squeezing men to death at the point of orgasm with her thighs. Very queer. In fact, she’s quite literally so in the uncut version of the film which was eventually (in 2006) released in the UK as a ‘15’ certificate DVD. All previous versions had chopped out the part of the fight in the Cuban jungle where Natalya tries to fight Xenia but is gripped between her thighs and told to “wait for your turn”.

The earlier moment where she sucks on her fingers when Trevelyan boasts to Bond of Natalya tasting “like strawberries” could be taken either way.

Although at the time I was unaware, consciously at least, of Xenia’s intended bisexuality, I must have sensed that there was something different about her (beyond the whole squeezing-people-to-death part). There were no ‘out’ characters in mainstream games back in 1997. As some, including expert Aoife Wilson, have pointed out, they are still too thin-on-the-ground today. But Xenia was the closest thing I could get.

The only other character I chose to play as was principal Bond girl Natalya Simonova and only then when someone else had already chosen Xenia. This didn’t happen very often though, and only when a new player joined us. Certainly, all of the GoldenEye lunchtime regulars knew that David and Xenia were inseparable and you definitely shouldn’t try to get between them.

But why?

Dr Jaigris Hodson concluded in a 2017 paper that:

The reasons why people choose to play a specific game or avatar within that game are very complex, and the content of the game, along with the reasons people choose a gendered avatar, or how they relate to the avatar both support and subvert dominant gender norms.

In other words, some people choose characters which are most like their real-life selves and others use them to explore alternative identities.

Dr Hodson called her paper ‘Playing in Drag’ and this is a recurring idea in the literature. Pamela Livingstone, for instance, interviewed games players and found playing as a gender-swapped character “can be much like dressing in the clothing of the opposite sex”. Furthermore, it allows you to “experience all the things (associated with the other sex)”.

I’m not saying my choice to play as Xenia was because I wanted to feel like a woman. In all honesty, I’ve never spent that long pondering whether my brain is ‘male’ or a ‘female’, which probably means I am a ‘man’. Trans people have told me they felt their gender dysphoria eating away at them from an early age. I have never experienced this but I imagine it’s a bit like straight people not agonising if they are ‘straight’, unlike many gay people for whom it is never far from their thoughts.

I think I chose Xenia because I saw some of my difference reflected in her. In the film of GoldenEye, Xenia is far more of a ‘freak’ than main villain Alec Trevelyan, the former 00-agent who’s essentially the self-serving version of 007. Interestingly, few of my friends ever played Bond. Perhaps no one wanted to be that much of an ego-maniac.

Although there are many times in my life when I have sought to emulate Bond, playing GoldenEye 007 with my friends was never one of them. In the hundreds of games we played, I never chose the main man himself.

A desire to be different, or at least try out a different way of life, is not confined to queer people of course. Becky Chambers, a journalist and author of series of science-fiction books featuring non-binary characters, cites the experience of a player identifying as a straight, cisgendered man:

If the gender of the character didn’t affect the story too much, then female characters were usually easier for him to relate to than their hyper-macho, gravelly-voiced counterparts. The typical portrayal of men in games was so far removed from his own identity that he often found it easier to play a woman.

Maybe this explains why my straight male friends chose not to play as James Bond: they couldn’t relate to him. But what made Xenia so relatable to me?

Perhaps I was attracted to Xenia because she has what so many female characters - in popular films as well as games - lack: agency. Feminist critiques of games regularly call out titles which only include characters as ‘damsels in distress’ waiting to be rescued by a male character. Anita Sarkeesian focused a whole series of her Feminist Frequency YouTube series on this all-too-common ‘trope’. Natalya is definitely in the damsel mould in the game of GoldenEye, having far less agency than in the film. In the game’s most frustrating single player level, the player (Bond) must protect her from swarms of machine gun-wielding bad guys while she reprograms the GoldenEye superweapon. Seemingly unable to pick up a gun to defend herself, Natalya’s death signalled Game Over many times over for me on my first playthrough. It’s probably why I only ever chose Natalya for multiplayer if someone else had taken my beloved Xenia. She was a very distant backup choice.

I feel bad for spurning Natalya, but can you blame me?

In the film of GoldenEye, Xenia is the one who drives the plot, right from after the pre-titles sequence. Trevelyan doesn’t even rear his traitorous head until halfway through. She is far more proactive than reactive. Xenia is always unrepentantly true to herself, right up until her end, something that can’t be said for someone like May Day in A View To A Kill, who comes good before being blown to smithereens. Even her death is entirely appropriate for her character, being squeezed to death in the fork of a tree after 007 shoots dead the pilot of the helicopter she’s attached to. A fitting, and memorable, end. As Bond quips: “she always did enjoy a good squeeze.” Even in the game she is far more powerful than Trevelyan. All the player has to do is push him off the bottom of a satellite dish, whereas Xenia is staking out a huge patch of forest and lobbing grenades at you. To defeat her you really have to keep moving - and firing a lot of ammunition. She’s a tough adversary.

Just when I was starting to think my obsession with Xenia was borderline unhealthy I find out I’m not alone in my admiration. Calvin Dyson, another gay Bond “mega-fan”, whose videos have over five million views on YouTube, tells me his experiences mirror my own:

I was ALWAYS Xenia! And if, some reason I couldn’t be her, I would be Natalya. There’s definitely something to that isn’t there? A bit like how every gay gamer I know who played Mario Kart when they were 10 would always be Princess Peach.

For the record, I usually played as Yoshi in Mario Kart, but he’s one of the least conventionally masculine characters and ‘other’ in the sense that he’s a dinosaur, whereas most of the other choices are humanoid. Calvin’s experiences are so similar to my own that they can’t just be a coincidence.

I hate the stereotype that gay men are feminine, somehow less of a ‘man’ than ‘real men’. People who spout such nonsense are usually those whose own sense of identity is the least secure. So many men - queer and not - have mental health problems because they can’t live up to masculine ideals. I wasted far too much of my life worrying if that gesture, that pronunciation or that preference in music was ‘too gay’. Now I just accept everything I am. Who cares if we have qualities considered by others to be ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’? Only the most troglodytic of people still see gender in such binary terms. Video games give us the opportunity to work out not just what we do or don’t like, but who we are and might be.

Above all, maybe we should all embrace our inner Xenia and stop caring so much about what others think. Just don’t let her embrace you with her thighs. It won’t end well.

Which characters do you prefer to play as in games? Do they conform or subvert your own sexual orientation or gender identity? Leave your comments below.