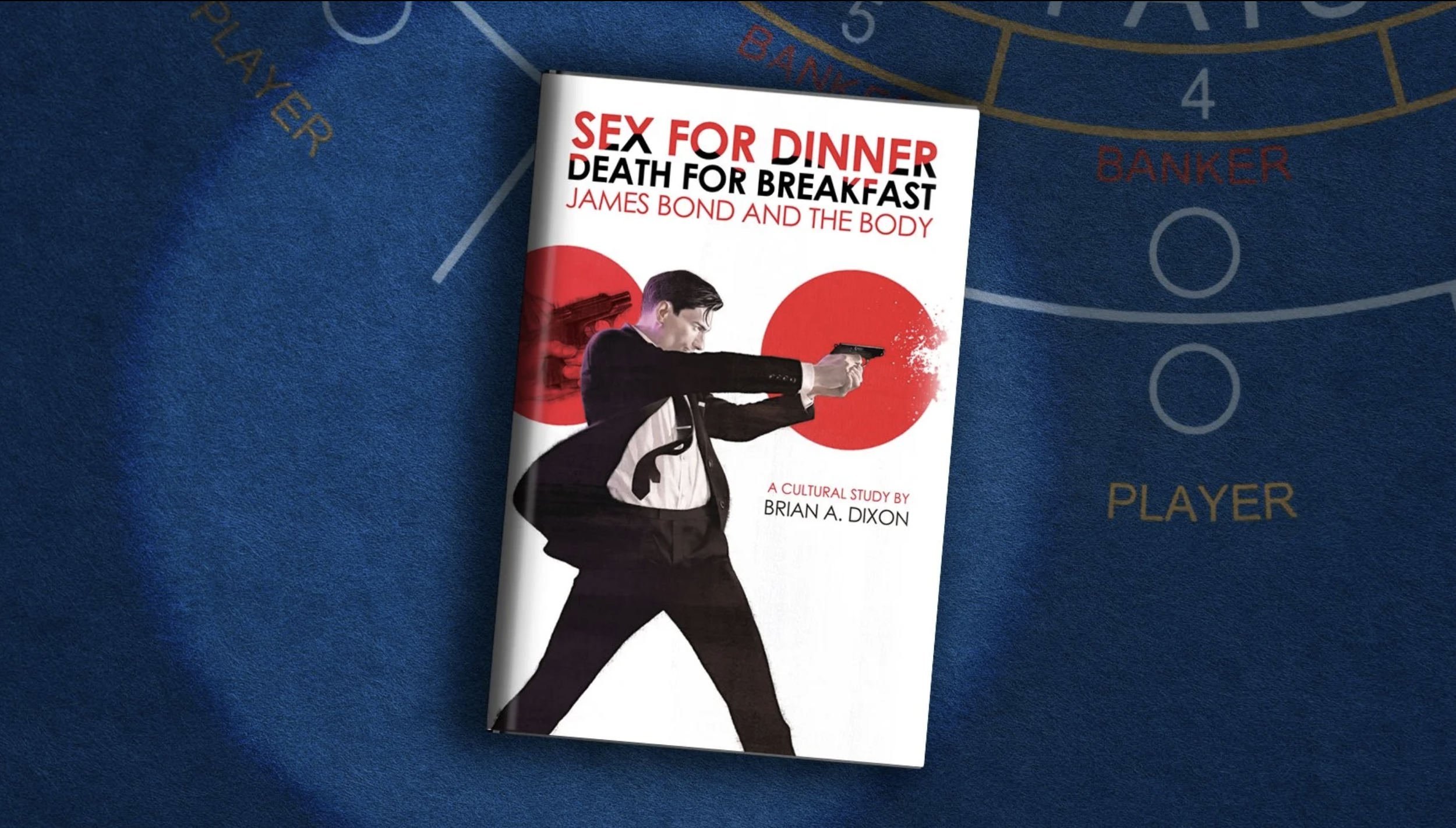

Sex for dinner, death for breakfast: James Bond and the Body

James Bond’s body has received a lot of attention over the years from Bond Girls and sadistic villains. Finally, it gets the academic treatment it deserves. Rarely does a book on Bond come along which manages to be as entertaining as it is illuminating.

Reading Brian A. Dixon’s Sex for Dinner, Death for Breakfast: James Bond and the Body, I was reminded of the ancient Buddhist parable ‘The blind men and an elephant’. In the story, six blind men grab on to different parts of an elephant’s body. Unable to take in the elephant as a whole, each mistakes their part for something else: the trunk (mistaken for a snake), tusk (spear), ear (fan), leg (pillar), side (wall), tail (rope).

Let’s hope the story is apocryphal. Having recently had an up-close and personal experience with an elephant myself, I am only too aware of how dangerous they can be when provoked. Having their various body parts manhandled simultaneously is unlikely to end well - for the men doing the manhandling at least. And we’re better leaving aside the backstory - why are the men groping an elephant in the first place?! Instead, let’s just acknowledge that the story speaks a universal truth: focusing our attention too much on a part can blind us (metaphorically) to the whole.

It’s an idea also expressed in the pithy idiom found in languages around the world - including Japanese, Chinese, Hungarian, Russian, Finnish, German and, of course, English - about not being able to see the wood (or forest) for the trees.

Despite the universality of this idea, this is precisely the trap that so many academics writing about James Bond fall into. By focusing on just one element that has drawn their attention, they ignore the bigger picture. Any academic writing on Bond worth reading must acknowledge that the Bond series is a massive phenomenon beloved by millions of people. Whatever the box office receipts and revenue from book sales, James Bond is something a lot of people love and feel personally connected with. But a great deal of academic writing about Bond seems to be on a mission to make those who actually love James Bond feel guilty for their ardour.

This is partly a consequence of academia still being divided into rigid disciplines. If I had decided to pursue a career as a university academic, I would be the person making a nuisance of myself in departments across the campus. While my obsessions run deep, I’m simply too curious about lots of different stuff to feel like I have to stay in my lane. I wouldn’t be satisfied with just my part of the elephant.

Just as Bond is strictly non-monogamous in the bedroom department, Bond has seduced academics from many disciplines, including geopolitics, psychology, cultural studies, literary and film theory, science and technology, gender and sexuality and more. The problem is, some of the academics behave like spurned lovers. They have their personal axes to grind and poor Bond can end up being merely the whetstone. They seem to have forgotten - willfully or not - that Bond is both a valid subject of serious academic study and something to be enjoyed. Perhaps because they are insecure about being taken seriously themselves, they mask their enjoyment with a tone which can come off as snide, if not downright disparaging.

I started Licence to Queer because I was both fed up with a lack of openly queer voices in the Bond space and exasperated with the superciliousness of so much academic writing about Bond. I wanted to read things which got beneath the surface of Bond’s appeal but never lost sight of Bond as entertainment. In the absence of academic writing which was also entertaining to read, I started doing it myself.

Rarely does an academic book on Bond come along which manages to be as entertaining as it is illuminating. Sex for Dinner, Death for Breakfast: James Bond and the Body is one such book. Its author, Brian A. Dixon, is a versatile academic who is not rigidly confined by a single discipline. Furthermore, he doesn’t let the entirely fabricated and facile distinction between ‘high art’ and ‘low art’ get in the way of serious discussion of an apparently silly subject. This is the only book on Bond I know of which offers a compelling feminist reading of the role Britt Ekland’s backside plays in defeating the villain of The Man with the Golden Gun.

As far as the body parts of James Bond himself are concerned: a miniseries of comics published in 2018 (The Body by Ales Kot) told stories centred around Bond’s gut, his brain, his heart and his broken bones; Toby Miller has tackled James Bond’s penis and its relationship with cultural imperialism; Daniel Craig’s muscle-clad frame has been held up as something aspirational - and, with a lot of effort, attainable - by various men’s lifestyle publications, including Esquire, GQ and Men’s Health; Bond’s body as something aesthetically appealing to be gazed upon has received some academic attention, especially among queer and feminist scholars (my own contribution is here).

But like the apocryphal blind men manhandling an elephant, these have ignored the bigger picture. It feels somewhat revolutionary to locate the whole appeal of Bond in his body as a whole. But Dixon dares to go there. He asserts in his opening chapter:

“The body of James Bond represents - then, now, and undoubtedly later - the body politic in its portrayal of what were, are, and may well be. The appetites of the characters who populate these adventures - for clothing, food, power, sex, and killing - are our appetites.”

In punchy (not a word is wasted) and lucid prose (how refreshing for an academic work on Bond!), Dixon unpacks his thesis with compelling examples drawn largely, but not exclusively, from the novels Casino Royale and The Man with the Golden Gun (the stories which bookend Fleming’s oeuvre) and their screen adaptations.

Given Fleming’s dictum that the only vital criterion for writing an effective thriller is making sure the reader keeps turning the pages, I find it disappointing that many writers of non-fiction don’t bear this in mind when writing about Bond. But here, barely a page goes by without Dixon bringing into the light something which had hitherto been in shadow.

I shan’t spoil anything here, but Dixon is one the very few commentators who have thoughtfully considered Bond from an audience response perspective, which is still a massive gap in the Bond academic discourse (one I have attempted to plug a little in an essay I’ve written for a forthcoming volume out later this year). In exploring Bond’s appeal to both men and women, Dixon points towards the feminine being foundational to the character. A close reading of the intensely sexualised passages at the card table in Fleming’s Casino Royale is a highlight.

I particularly enjoyed Dixon’s analysis of the extent to which the character of Bond provides an ‘instruction manual for social performance’, but one we cannot follow to the letter. The peril Bond continually faces makes palatable our failure to measure up to him. Death and sex are central to the appeal of James Bond: antithetical yes, but also working together to keep each other in check.

That Dixon feels brave enough to use dialogue from Die Another Day as his book’s title (and the book’s epigraph) speaks volumes. It’s a Bond film with few acolytes but it’s not without its pleasures. [I remain steadfast in acclaiming it as the ‘Shakespeare of Bond films’ on the basis that practically every line from an actor’s lips is laden with wordplay and double meanings. It’s a feast for cunning linguists. But I digress…] Miranda Frost’s verbal takedown of 007 (“Remember, I know all about you 007 - sex for dinner, death for breakfast. Well, it’s not going to work with me!”) may be intended as a character assassination, but it’s also unerringly accurate. Which is perhaps why Dixon adopted it for his title: he’s not afraid to be critical of the Bond phenomenon but he’s never off the mark. And he never lets being critical get in the way of enjoyment. The two are not incompatible. Other academics writing about Bond could learn a lesson here.