A whisper of love: the case for Bond as romance fiction

I used to think that romance fiction didn’t hold a special place in my heart. But then I realised I’d been reading romance all along, in the form of James Bond.

Heathcliff, Mr Darcy, Edward Rochester… James Bond?

James Bond doesn’t usually get mentioned in the same breath as these canonical ‘Romantic heroes’. But he fits the character archetype as snugly as Daniel Craig’s Bond fits into his blue trunks. Romantic heroes are typified by their intense introspection, alienation from society, and a strong, often rebellious, individualism. The literary Bond - and to an extent, his cinematic descendants - ticks all the boxes.

So why did it take me so long to recognise Bond as romance fiction?

Growing up, I was instinctively suspicious of reading romance. I was a voracious reader from an early age as a result of my parents having taught me to read before I started school. One of my earliest memories of school is being given the freedom of the library in the afternoons while the rest of the class had reading lessons back in the classroom. But even then, I can recall steering clear of picking up any book which looked like it might involve romance. In hindsight, I realise this was multifaceted. Part of it must have been survival instinct kicking in; reading romance would out me as gay. Even now, I suspect only the most secure heterosexual men would admit to reading romantic fiction. Another part of it was my growing awareness that romance was not for me; as a gay kid I couldn’t see being in a romantic relationship in my future. Working in schools as an adult, I marvel at the amount of LGBTQ+ themed books which stand proudly on our library shelves. But my entire time in education coincided with the Section 28 era, when teaching materials featuring any form of gay representation - including books - were explicitly suppressed. My whole childhood, I never learned that men could fall in love with each other. So why would I choose to read about something I could never have?

Any romance I did read in my school days was done so accidentally - and stealthily. By far my favourite genre was science fiction. Being in space was my safe space. Sci-fi is the place where you’re most likely to find non-normative identities, upended social conventions and the possibility of a better world out there, somewhere. You might even find romance as part of the story. But because there’s a cool looking spaceship on the cover, you can rest easy. No one will see you reading ‘gay stuff’.

A close up of a man’s naked back

Considering my caution about reading anything in public that might be construed as being even a bit gay, my mind boggles at the thought process that led eight year old me to take into school as my reading book my dad’s copy of Thunderball. The arresting cover for this 1963 Pan Books paperback edition features a striking illustration by artist Sam Peffer of a man’s naked back, penetrated by two bullet holes. Perhaps I felt safe because the cover also had JAMES BOND in thick black lettering at the top, loudly announcing to the world that this was definitely NOT a gay book. Not for the last time, but possibly the first time, Bond was my ‘beard’, my cover story concealing my true identity.

I certainly wasn’t conscious that I was reading my first romance novel.

I’m not the first person to recognise the romance streak in the Bond books.

In a damning review of Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me, The Times’ critic labelled the book a "trashy attempt at a romance novel" and accused Fleming of “literary transvestism” for writing in the persona of a woman. Perhaps the critic was especially opprobrious because then, as now, writing romance is seen as pursuit for women. It’s estimated that less than a fifth of romance books are written by men, although it might be more. It’s hard to pin down because men who write romance often adopt female noms de plume. Somewhat ironically, the originators of the genre, including the creators behind Heathcliff, Darcy and Rochester, all published their works under male names or anonymously to maintain respectability.

Far more insightful about Fleming’s romantic leanings was Kingsley Amis, who, in his 1965 study The James Bond Dossier, observed that while the Bond books are generally categorised as thrillers, they follow a repetitive romantic structure: Bond meets a ‘maiden in distress’, they experience a shared ordeal, and the story ends with a temporary ‘happily ever after’.

Thunderball fits this structure very neatly. What surprised me as an eight year old who had only experienced the world of Bond through the films, was quite how many pages Fleming devoted to the relationship between Bond and the girl. Domino is a fully fleshed out character and the ‘meet cute’ with Bond is brilliantly rendered.

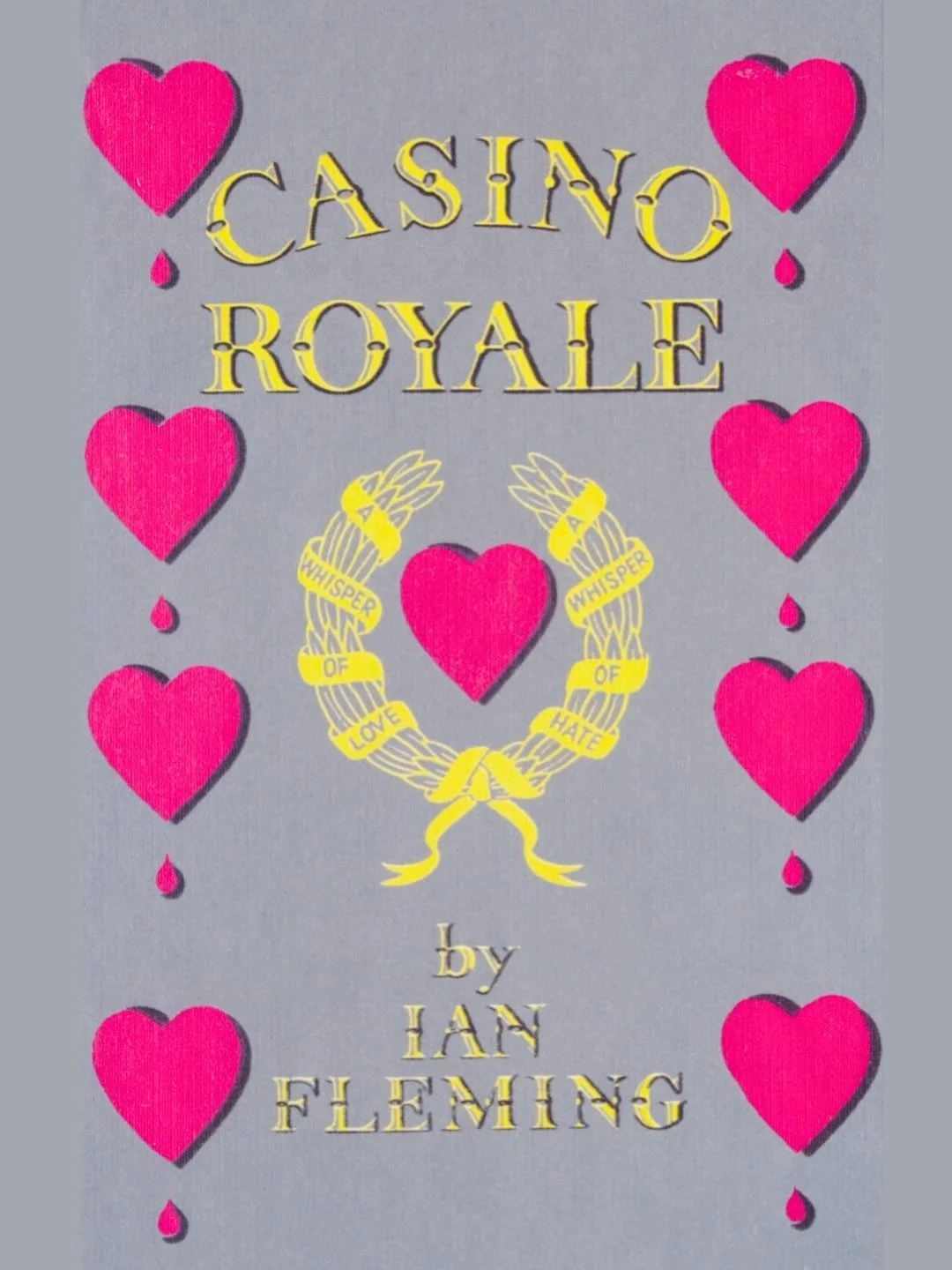

Not all Bond books fit the ‘happily ever after’ romance mold as easily. Bond almost always ‘gets the girl’ in some capacity, but in nearly half of them (Casino Royale, Moonraker, From Russia, With Love, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and The Man with the Golden Gun), there are complications. As Fleming himself reflected, “Bond may get the girl, but I make him suffer for it.” Moonraker is particularly notable in this regard. It’s the Bond book I always recommend to people who are suffering from a broken heart.

But while a happy ending might seem desirable in the romance genre, it’s hardly a prerequisite. After all, what great romance - in real life or in fiction - doesn’t involve at least a little suffering?

A history of violence

Like Heathcliff and the other brooding 18th Century romantic heroes, Bond was a product of a particular time period, something Fleming was acutely aware of. In his final interview before his death, Fleming felt the need to justify the violence in his books: “The simple fact is that, like all fictional heroes who find a tremendous popular acceptance, Bond must reflect his own time. We live in a violent era, perhaps the most violent man has known.”

Bond’s Romantic (with a capital ‘R’) brethren were written into life in an epoch characterised by violent conflict between the old world and the new. The Romantic Era of the early 1800s was less to do with falling in love and more concerned with trying to hold on to some beauty and humanity in a world being forced to rapidly rationalise and industrialise. These Romantic heroes embody this struggle. As a result, none of them are especially likeable people, especially when divorced from their original context. It’s something of a worry then that Heathcliff (Wuthering Heights), Darcy (Pride and Prejudice) and Rochester (Jane Eyre) are nowadays held up as romantic (with a small ‘r’) ideals. A relationship with any of them would surely be deeply unpleasant and, sooner rather than later, doomed. Just like Bond then.

It’s interesting that numerous actors who have played Bond or been thought of as a natural fit for the role have also played Heathcliff, the most ‘toxic’ (in modern terms) of the Romantic heroes. They include Timothy Dalton, Ralph Fiennes, Tom Hardy and Richard Burton. Modern adaptations of Wuthering Heights choose to smooth - or shave off entirely - the character’s rough edges. Doubtless some of this is commercially-driven but some of it comes down to wilful misreading. Screenwriters are not immune to the fantasy of being able to tame a bad boy. But I think the appeal comes down to more than wanting to be with a bad boy. Many of us want to be the bad boy ourselves. Beneath the brooding exterior, we glimpse deep inside the Romantic hero something we might recognise as a desire to connect. For those of us who have spent significant periods of our lives feeling unlovable, we may identify with such characters because they provide a degree of hope that there may be people out there who can see through the walls we’ve put around ourselves. Or, to use the metaphor from the 2006 film adaptation of Casino Royale, people who can strip away our armour.

Fleming was adamant that while "Bond is not a hero” (I.E. in the unRomantic sense) he’s also “not a bad man.” Like any archetypal Romantic hero, Bond represents a whisper of love in a hateful darkness that sometimes threatens to deafen us.

We live in a world which is designed to keep us isolated while making us crave connection - and feel there is something wrong about ourselves when we don’t have it. Astride this contradiction, Bond stands as a reminder: like all Romantic heroes, Bond can function on his own up to a point. But he also reminds us of the value of making connections, of all kinds.

First time readers of Fleming’s books are often surprised to find out how frequently Bond falls in love. He strongly considers marriage on numerous occasions, though whether this is for the sake of social respectability or not is never clear. Fleming himself was faced with this dilemma and chose to do the honourable thing, perhaps to his regret. At times, the Bond of the books even comes across as overly eager to form a lasting connection with the people he meets - both with the girls he usually ends up bedding and the various male allies with whom he forges intimate, even homoerotic, friendships almost instantly.

Bond’s dating history is defiantly unheteronormative, having more in common with a stereotypical gay man. Perhaps it’s a consequence of his chosen profession; whether because of the itinerant nature of a secret agent or the inherent dangers of the spheres he operates within, the vast majority of the connections Bond makes are inevitably short-lived. Or maybe he just has a lot of love to give.