The Queen, queers and country: a tribute to Her Majesty

For 70 years, Her Majesty was the only consistent recurring 'character' across the different versions of Bond, serving as an inspiration for many, including women and those men who had to keep their sexuality secret.

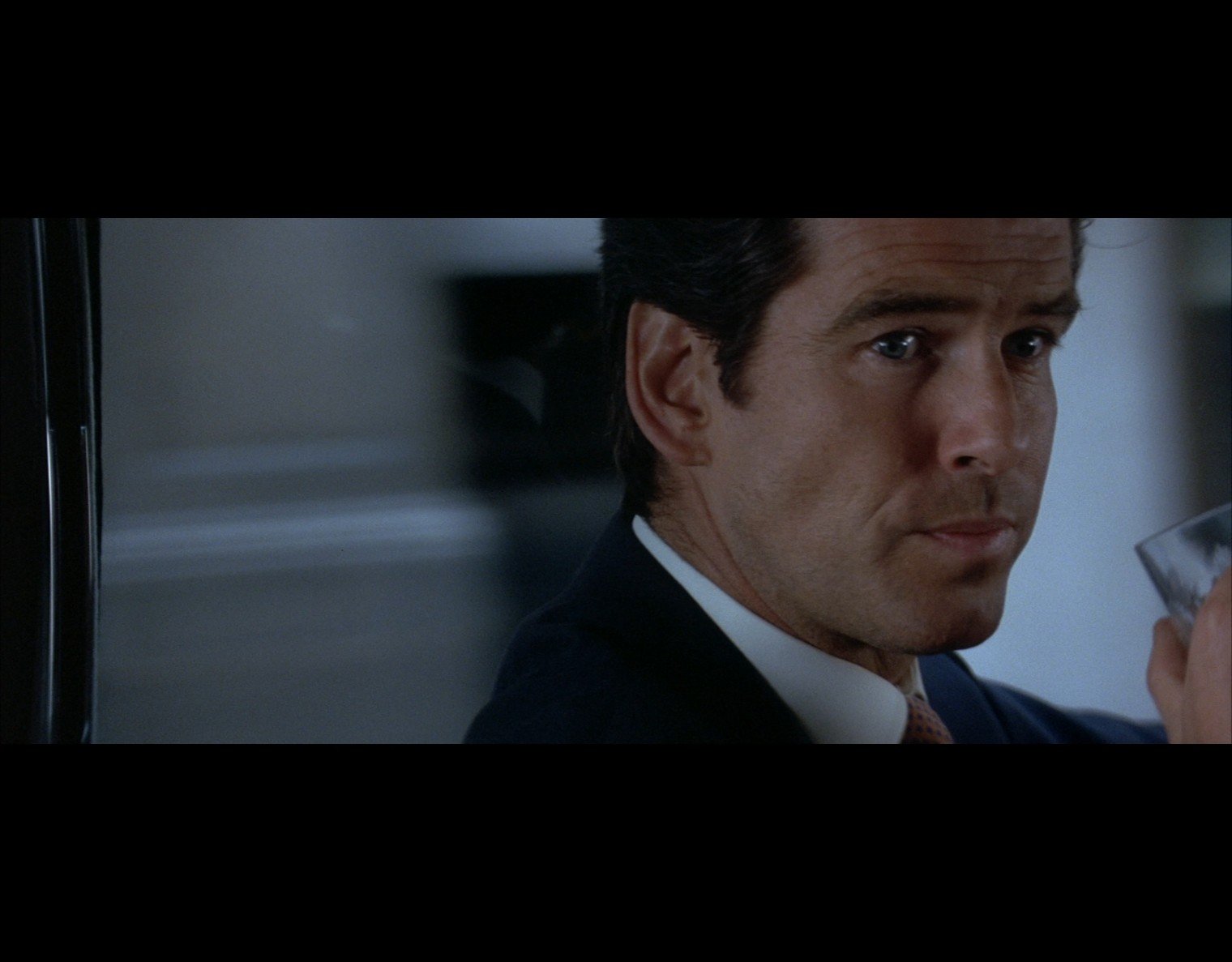

M: I believe you once had a relationship with Carver's wife, Paris.

Bond: That was a long time ago, M. Before she was married. [Glaring at Moneypenny] I didn't realise it was public knowledge.

Moneypenny: Queen and country, James.

Of all the scenes which mention the Queen in a Bond film or book (and there are a lot of them), it might seem strange that this is one which resonates most of all with me as a queer Bond fan. It’s rare for Bond (especially Brosnan’s Bond) to have an air of diffidence, but here he looks genuinely taken aback at being the subject of office gossip. His love life has been discussed by M and Moneypenny. His secret is out in the open. Robinson attempts to display manly disinterest, awkwardly clutching his glass of bourbon. Two strong women run verbal rings around 007, effortlessly slipping in innuendos galore, passing the ‘pumping’ metaphor back and forth as if they are rallying tennis players, Bond being the ball.

Do we identify with Bond, the outed one, or the women? Perhaps both.

A lot of gay men relate to strong women. Because many of us are not conventionally masculine, we can identify with certain women more easily. This extends to princesses and queens, perhaps because they have more often than not had to assert themselves in a man’s world.

One can’t help wondering what the Queen would have made of this setup: her loyal terrier being ordered to pump a former lover, the villain’s wife, for information. Tomorrow Never Dies was one of the few Bond films not to have a member of the Royal Family at the premiere. The Queen did attend the premiere of Die Another Day however. As far as I am aware, she never went on record with her feelings about the film so we don’t know what she made of the “mouthfuls” of double entendres and the numerous “cockfights”. A woman of the world, I doubt the Queen would have been remotely appalled.

Die Another Day prominently features Buckingham Palace. When I was invited there in 2019 (for a garden party in recognition of my ‘Services to Education’, not a knighthood), I couldn’t help affecting a little Gravesian/Bondian swagger as I walked through the gates. Yes, we were in a place relatively few get to go so it all felt very VIP-ish. But above all, we were so excited because we were in the residence of the woman who has provided the country - and the Bond series - with such enduring continuity.

Although Bond was fictionally born six years before the Queen (according to John Pearson in his Biography), Bond’s adult adventures have all taken place during the reign of Elizabeth II. We have had multiple versions of the recurring characters - M, Moneypenny, Felix Leiter, Q, Tanner - and of course Bond himself. But we’ve only had one Queen.

Queen Elizabeth II’s reign began on 6th February 1952, fourteen months before Casino Royale was published (on 13th April 1953). The Queen wasn’t mentioned directly by Fleming until the third novel Moonraker, published on 5th April 1955, although Fleming then made up for lost time, bringing her into almost all of the subsequent books in the series.

In addition to providing what little continuity is worth holding onto in the world of Bond, perhaps the regular cameos of the Queen have a deeper resonance for some of us. They’re a reminder for all of us that Bond ultimately has had, for 70 years, a female boss, something about which he’s pretty nonplussed. If only all men could follow his example, we might just have less sexism and homophobia to contend with.

When the first Queen Elizabeth addressed the land army assembled for the eventuality of the Spanish Armada breaking through, in May 1588, she addressed the giant sexist elephant in the room: “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman but I have the heart and stomach of a king.” A precursor perhaps to Judi Dench’s M in Tomorrow Never Dies, taking great delight in telling Admiral Roebuck that, while she does not possess male genitalia, this does means she has a greater capacity for rational thought.

Compared with the first Queen Elizabeth, the second was less apologetic about her chromosomal constitution. For her 1966 Christmas message, she chose as her subject the era’s strides in gender equality, expressing that it was “difficult to realise” that women had only been able to vote for less than half a century. She went on to observe that: “it has been women who have breathed gentleness and care into the harsh progress of mankind. The struggles against inhuman prejudice, against squalor, ignorance, and disease, have always owed a great deal to the determination and tenacity of women.”

Earlier in the same speech she had spoken of both men’s and women’s “flames of compassion” being the inspiration for “humanitarian legislation.” A constitutional monarch has to choose their words carefully. But it’s hard not to infer from this that she wasn’t at least in part referring to the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, legislation which had already been through the House of Commons twice by this point and which would receive the Queen’s Royal Assent seven months after she made this speech.

Let’s not forget that homophobia swims in the same cesspool as misogny: the fear being that men might somehow be ‘unmanned’ merely by loving other men. And what’s wrong with being a woman anyway?!

Aside from in portrait form, the Queen only appears on screen with Bond once, becoming an actual Bond Girl in the short film made for the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics. It’s a celebrated moment, justifiably. Although what’s less celebrated is that, when you stop to think about it, it’s Her Majesty in the Bond role, plummeting from the sky below a Union Jack parachute a la Roger Moore in The Spy Who Loved Me (her pink dress an arguably less conspicuous costume choice than a bright yellow ski suit). Further queering the moment, the skydiver that wore the pink dress, doubling for the Queen (sorry to shatter the illusion), was a man.

For his own part, Bond appears to have nothing but respect for the Queen. In Fleming’s The Man With The Golden Gun, he refuses a knighthood in recognition of his country-saving efforts, but he does so because he does not want to sacrifice his anonymity. In one incarnation of 007, he does eventually relent, becoming Sir James Bond in 1967’s Casino Royale. When M is trying everything to get David Niven’s asexually-coded Bond to come out of retirement he plays what he thinks will be his trump card: a letter addressed to Bond from the Queen herself. Bond’s reponse is “not even for her.” The message is clear: if he won’t do it for Her Majesty, he won’t do it for anyone. End of story. His loyalty to her is never, however, in dispute.

In more ways than just their loyalty to their country and each other, Bond and the Queen are synonymous.

They share a taste in strong drinks. A year before her death, it was widely reported that the Queen had been advised to give up her favourite evening tipple: none other than a dry Martini.

Fleming underscores Bond and the Queen being synonymous in the novel of From Russia, With Love. The Soviet intelligence services are seeking to undermine the credibility of England’s intelligence services (and by extension, England itself and its head of state) by shaming and destroying their most visible symbol: the heroic James Bond. In their analysis:

"The English are not interested in heroes unless they are footballers or cricketers or jockeys. If a man climbs a mountain or runs very fast he also is a hero to some people, but not to the masses. The Queen of England is also a hero..."

Here Fleming refers to the Queen as a ‘hero’, curiously abstaining from using the gender-marked form ‘heroine’. In Fleming’s conception, the Queen is, at the very least, a man’s equal. And not just any man: the equal of James Bond.

For more on Bond and royalty, see my queer re-view of The Spy Who Loved Me.

This is a great thread of Queen references in Fleming: https://twitter.com/BondMaps/status/1568973038628085760?t=3PlUj_dB74hib9AlwCE0gw&s=19

Thank you to my husband, Antony, for the inspiration.