This happened to another fella

Bond asking Tracy to marry him is one of the most rapturously romantic scenes in cinema history. Its modesty and gender equality subvert what we expect from a traditional marriage proposal. Without me realising until now, I think it may have influenced my own…

It’s no one’s idea of a romantic idyll: on the run from people eager to kill them, Bond and Tracy seek refuge wherever they can. It happens to be inside a stable. And it happens to be Christmastime.

The setting, modest as it is for a marriage proposal, makes On Her Majesty’s Secret Service echo another powerful story which much of the audience will be familiar with, even if we don’t make the connection consciously. Whether we are ourselves Christian or not, many of us live in cultures where we are taught from an early age that momentous things can spring from humble locations - and that includes stables.

So far, so potentially portentous. However, the marriage proposal that follows is (soft focus aside) refreshingly down-to-earth.

It’s not a performance for the benefit of friends and family. Only Bond and Tracy will remember the circumstances of their deciding to get married. Nor is it, despite the scene’s potential for religious symbolism, ritualised. Aside from it being the man doing the asking, neither he nor her feel the need to tick a pre-ordained list of boxes. There’s not even a ring. Although the gunbarrel that opens the film bucks convention by having Bond kneel, Bond does not get down on one knee when he proposes to Tracy. She is above him, but there’s no hint of subservience in either of them. As marriage proposals go, it’s natural and unforced, arising organically from a conversation between equals:

James: Tracy, an agent shouldn’t be concerned with anything but himself.

Tracy: I understand. We´II just have to go on the way we are.

James: No. l’II have to find something else to do.

Tracy: Are you sure, James?

James: I love you. I know l´II never find another girl like you. Will you marry me?

Tracy: Do you mean it?

James: I mean it.

Tracy doesn’t even feel she needs to say ‘Yes’. Instead, she and Bond launch into badinage about their future address. To cap it off, the scene ends with a satirical swipe at the convention of not having sex before marriage.

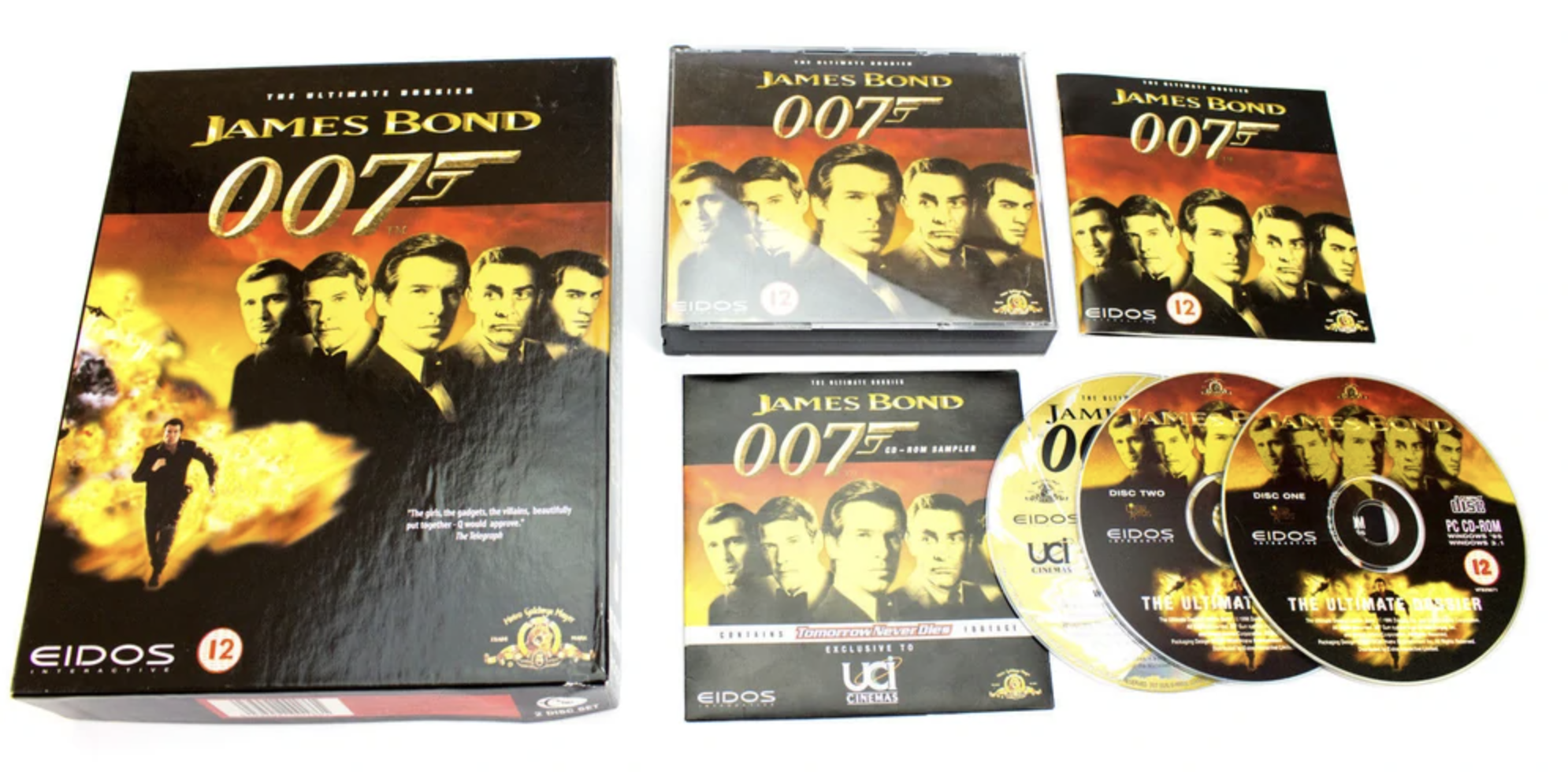

Back in 1996, before it was as easy as looking up your favourite film clips on YouTube, this particular scene was my most watched on the James Bond Ultimate Dossier CD-ROM (younger readers may need to Google ‘CD-ROM’. Incidentally, I have just checked and ‘Google’ wasn’t a thing until 1998. Gosh, I feel old all of a sudden.).

As a teen, I played this clip over and over again. A pretty ‘gay’ thing for a fourteen year old boy to do, but, y’know, if the cap fits and all that.

I felt tears forming every time Tracy said “Do you mean it?”. Perhaps I was putting myself in Tracy’s place, imagining that somehow, someday, someone would find it in their heart to love me like she was loved by Bond. Or maybe I was affected so deeply because of the pause before Bond responds - and all that it contains: the person who thought he would never be capable of forming a meaningful emotional connection has been taken by surprise. Maybe my own future was not as doomed as society had led me to believe?

I certainly wasn’t audacious enough to entertain the idea that someday I could ever get married. The option just wasn’t there. Like many gay people, I formed no mental model of marriage, or no positive one at least. Consequently, I found marriage proposal scenes in other movies revolting. But the one in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was not only bearable, but also aspirational.

On 24th July 2014, my partner (now husband) and me decided to get married. There was no formal proposal. It just slipped into conversation. This is how I rendered the (non)event for a recent book called The Everyday Lives of Gay Men:

Our proposal took place while we were doing the washing-up after dinner one night.

We’d just got back from visiting the new library and were wondering, aloud, if our local city council hired it out for weddings. I offered to phone them the next day to make enquiries.

And that was it.

No proposal on a gondola. No ring dropped into a glass of champagne. No sunset tête-à-tête planned with military precision. Either of us getting down on one knee just didn’t seem … necessary.

I always said I’d never get married, mostly because I couldn’t picture it happening. Maybe being surrounded by those billions of words in the library helped change my mind. I had to relearn the word ‘marriage’, modify its meaning – as we all did in England in 2014.

Love had recently won the day, and perhaps, in hindsight, we were riding high, drunk on the idea that anything was possible. This was in late July. Nine months later, as if we’d had to get married for a more Victorian reason, we said our vows. We adapted the words from the books which had shaped us, made us feel better about ourselves. We wore paper flowers made from pages of Nineteen Eighty-Four, quoted lines from X-Men in our personal declarations, threw in a Native American blessing at the last minute because the lovely registrar liked it. Why not bring more persecuted people into it?

It felt like we were making it up as we went along, because, in most ways, we were. We wrote ourselves into each other’s lives.

Hindsight can distort the facts of a situation and, more than 007 years after the event, I don’t for a second believe I was emulating Bond by being so nonchalant. But I find it interesting that I segued into somehow becoming engaged without any of the ritual associated with proposals. Maybe this was the only way it could have happened, my idea of ‘marriage’ being defined, at least in part by On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

A bachelor’s taste for freedom

The novel’s version of the proposal is just as spontaneous as the film’s (and my own).

After Tracy has helped Bond escape from Blofeld, they both have a quick breakfast at Zurich airport before Bond has to fly back to London, leaving her to escape over the Swiss border into Germany by car.

Bond suddenly thought, Hell! I'll never find another girl like this one. She's got everything I've ever looked for in a woman. She's beautiful, in bed and out. She's adventurous, brave, resourceful. She's exciting always. She seems to love me. She'd let me go on with my life. She's a lone girl, not cluttered up with friends, relations, belongings. Above all, she needs me. It'll be someone for me to look after. I'm fed up with all these untidy, casual affairs that leave me with a bad conscience. I wouldn't mind having children. I've got no social background into which she would or wouldn't fit. We're two of a pair, really. Why not make it for always?

Bond found his voice saying those words that he had never said in his life before, never expected to say.

'Tracy, I love you. Will you marry me?'

She turned very pale. She looked at him wonderingly. Her lips trembled. 'You mean that?'

'Yes, I mean it. With all my heart.'

She took her hand away from his and put her face in her hands. When she removed them she was smiling. 'I'm sorry, James. It's so much what I've been dreaming of. It came as a shock. But yes. Yes, of course I'll marry you. And I won't be silly about it. I won't make a scene. Just kiss me once and I'll be going.' She looked seriously at him, at every detail of his face. Then she leaned forward and they kissed.

Although an airport is arguably a smidge more romantic than a stable (and I’ve encountered many more fictional proposals taking place in the former than the latter), both are liminal spaces where people are in a transitional state, literally moving from place to place as well as psychologically. Being in such spaces might lead them to question the courses of their lives and make life-altering decisions without giving them much prior consideration.

Image copyright Getty Images

While less impulsive than his creation, Ian Fleming got married relatively quickly when the possibility presented itself. Although Ian and Ann had been lovers for more than a decade, Ann was married to two other men in this time. Ann and her second husband agreed to divorce in late 1951, making it possible for her to marry Fleming.

Fleming biographer Andrew Lycett believes it likely that Fleming felt compelled to marry the recently divorced Ann because they had a baby on the way (son Caspar would be born in August 1952). Despite Fleming being an avowed bachelor, Lycett posits that “Ian had a very conventional side and, as Ann certainly knew, he could be relied on to “do the right thing, albeit reluctantly”.

Six days before they wed, Fleming had finished the first draft of Casino Royale. Fleming has often been taken at his word that he brought Bond into existence to take his mind off his impending nuptials but Lycett argues that he was also motivated by several other factors, including outdoing his brother (who had recently published a spy story himself), impressing his fiance and her literary friends and securing a income for his growing family. Perhaps most significantly, the soon-to-be-betrothed couple had, for the sake of the baby, forsworn sexual intercourse. Lycett renders this diplomatically: “Ian had time and energy on his hands”.

No wonder then, that the novel was, in Lycett’s words, a “literary manifestation of their sado-masochistic relationship”. Casino Royale, written in the short period between Fleming deciding to marry and actually going through with it, is a sort of love letter between people who had no need of showy gestures of affection.

Ian and Ann married in Jamaica on 24th March 1952 (Fleming and I miss sharing a wedding anniversary by only four days!), having got engaged only two months previously. To my knowledge, no details of the proposal have surfaced, although considering the circumstances, it was probably even more modest than Bond’s and my own.

Image copyright Getty Images

A study into marriage proposals published in 2022 acknowledged that research on the subject is still thin on the ground, surprising considering how commonplace proposals themselves are. An earlier sociological study, in 2004, concluded that it’s precisely because proposals are so commonplace that they are under-studied: they’re just a norm that the majority of people accept and don’t question.

Norms can be hard to deviate from. Although the institution of marriage has technically excluded same sex couples until very recently (the Netherlands was the first country to legalise same sex unions in 2001), it’s becoming increasingly clear from the historical record that same sex couples have been using the language of marriage to describe their relationships, and even engaged in marriage rituals, for centuries. Evidence exists from a wide range of contexts, particularly those where people of a single sex predominated, such as on prison ships, and particularly in places where love could outrun the law, such as the American West.

Image copyright Nini-Treadwell Collection

In the 31 countries where marriage equality currently exists, same sex couples are welcome to question the norms, or emulate them. They may even feel compelled to go bigger, and who can blame them for planning a dramatic declaration of their love, compensating for all those years where they thought such things were outside the realm of possibility?

Or they can - like Bond, and me - be spontaneous, and not so much ‘pop’ a question as drop it into conversation.

If you would like to read my full chapter inside The Everyday Lives Of Gay Men, you can do so here. You can buy a hardback copy of the entire book for the eye-watering sum of £120 (it’s technically an education book and they are usually pricey) on the Routledge website or download the whole thing for free (we all agreed to Open Access) here.

Images from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service from Thunderballs.