Queer re-view: Dr. No

You would think that a film which opens with three men pretending to be blind would alert us to the need to look at things differently. But six decades of straight-washing has obscured quite how queer Bond’s beginnings were. It’s high time we took the blinkers off: Bond was born this way.

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

This article is also available as a podcast, wherever you get podcasts. Apple and Spotify links below.

‘Inspired by Dr. No’ by Herring & Haggis

The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond

“He was popular with men and women - which is kind of unusual.” Sean Connery, interviewed by Mark Cousins in 1997 while watching the beach scene from Dr. No.

Bond may not be gay, but he has a gay sensibility, which appeals to queer viewers, especially - but not exclusively - gay men like me.

We all have our own ideas about what a ‘gay sensibility’ might be. The picture you have in your head when someone says ‘gay man’ will inevitably draw on stereotypes, less so if you happen to know gay men personally, more so if you rely on mass media’s distorted presentation of what we’re really like. According to Walt Odets, a psychologist with more than three decades of experience of providing therapy for gay men, gay men are distinct from their straight bretheren because they integrate conventional masculine and feminine traits.

James Bond fits this description perfectly.

It’s worth reflecting for a moment what makes men and women different. It’s less than you might think. Biologically-speaking, we’re identical for at least the first six weeks in the womb. And then the chromosomes start mixing things up a bit. Emphasis on ‘a bit’, or should that be ‘bits’, because sex mostly comes down to the sexual characteristics. Neuroscientists have shown conclusively that the differences between male and female brains are negligible. As one of those foremost neuroscientists, Professor Gina Rippon, pithily observes, “a gendered world makes a gendered brain”. Our brains are plastic and permeable and it’s the experiences we are exposed to - or held back from - as children which set us on our gendered paths, which are still too often seen as a binary.

As adults, how often do we pause and think about what these socially-constructed gender differences come down to, really? If you sit down and make a list, it all starts to sound a bit pathetic. Walt Odets observes that we all rely on “carriage, manner of speech, dress and ornamentation” to draw a line between men and women, all “socially dictated trifles that, in themselves, are inconsequential”. Of course, there are consequences socially - horrifying consequences sometimes - for both men and women who feel the need to strive for impossibly ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ extremes to prove their womanliness and manliness. There can be comfort in conforming to gender norms, but there can also be great pain. I think we’d all be better off if we accepted we were more ‘in between’ than at the extremes.

And that’s where James Bond comes in…

Ready for your close up, Mr Bond?

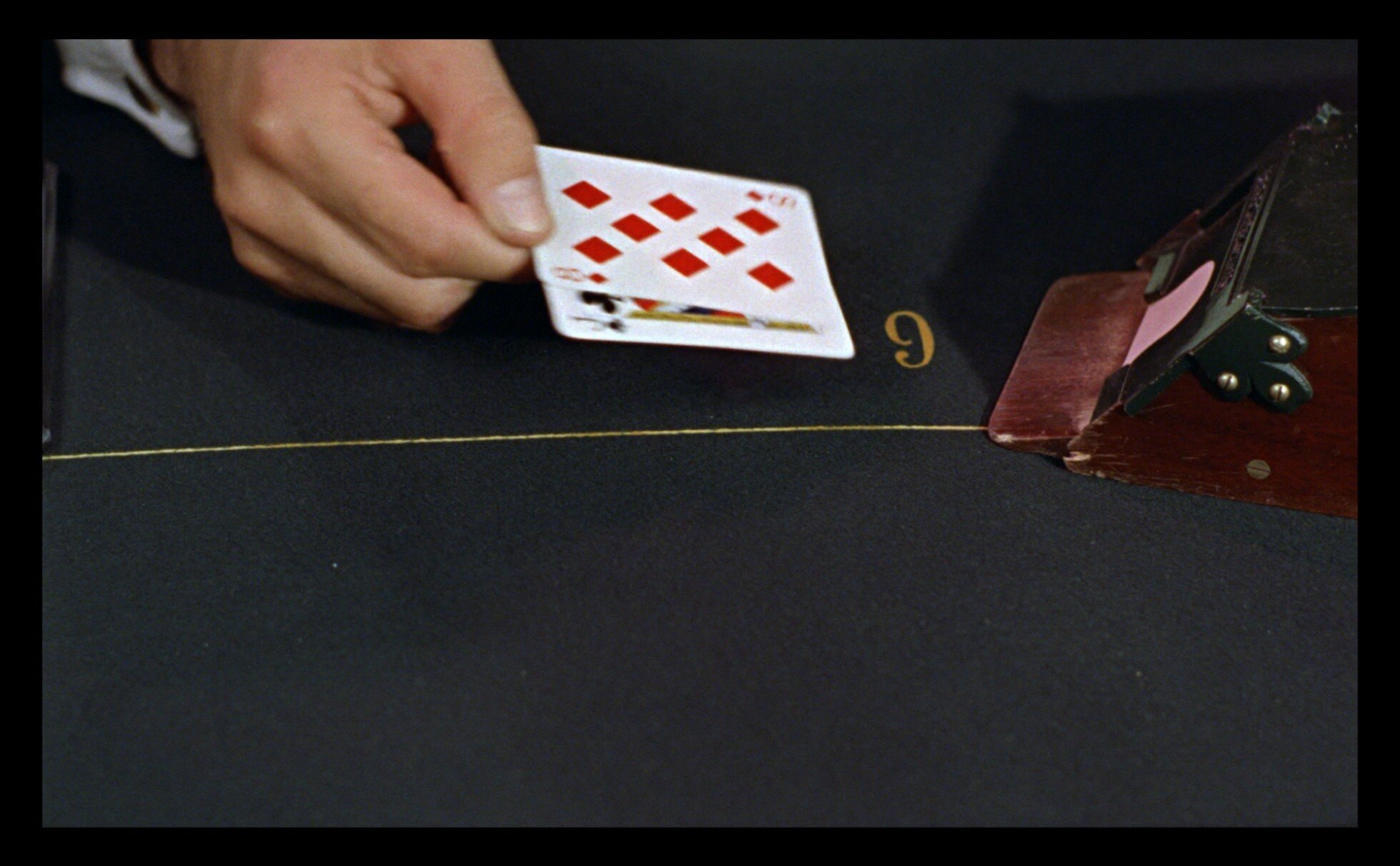

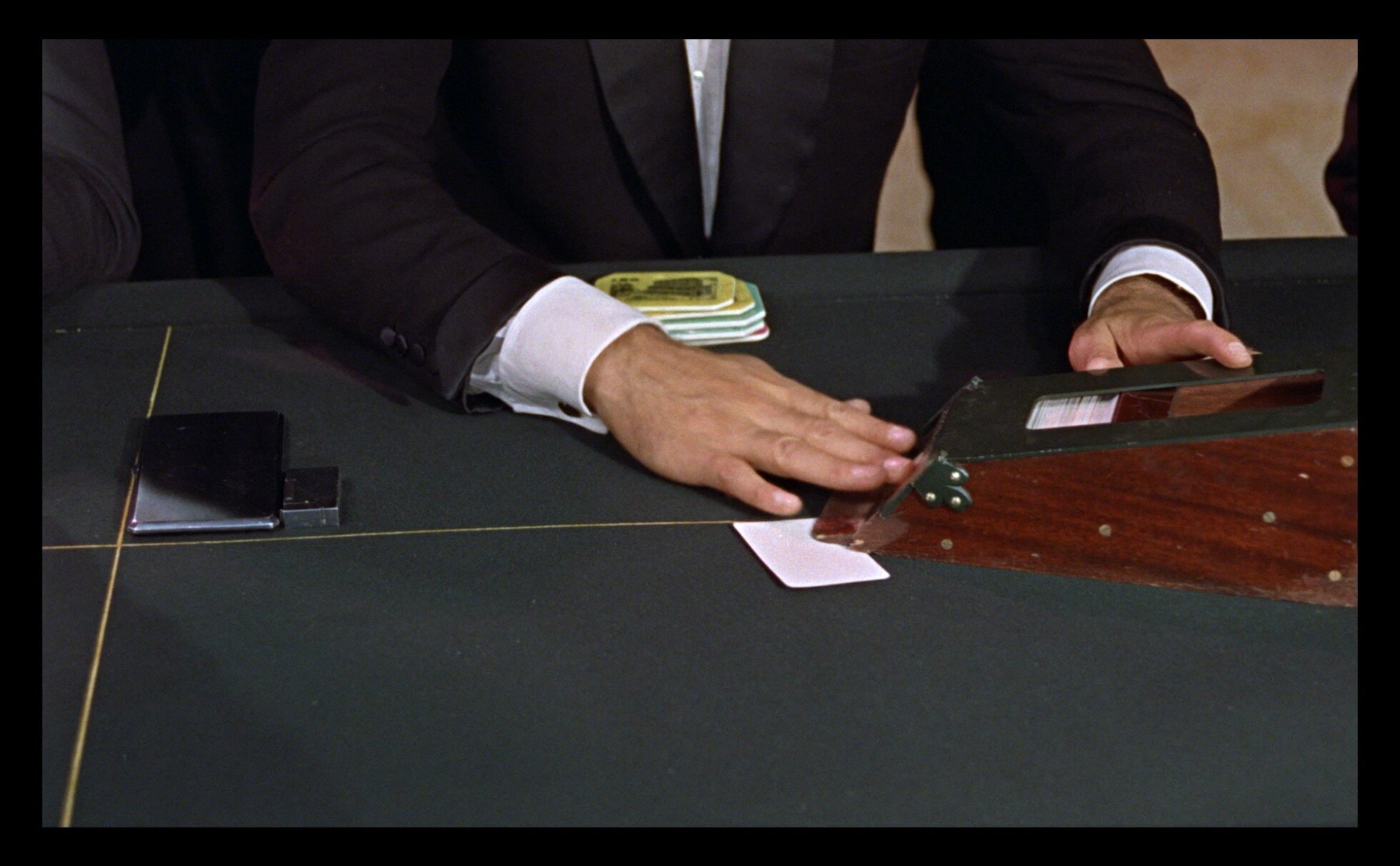

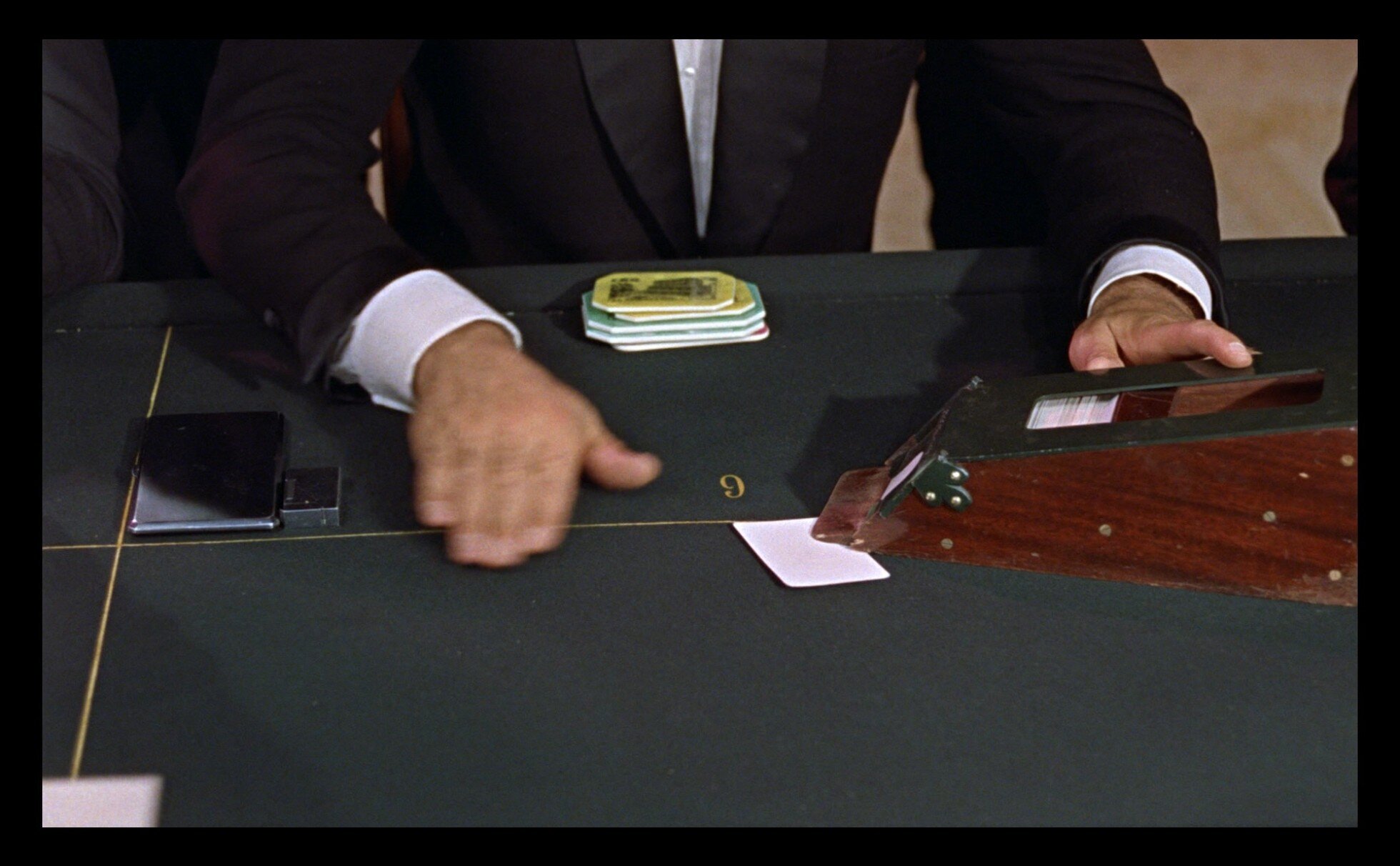

I’ve been convinced for a long time that James Bond is so appealing to me as a gay man because he presents an alternative version of masculinity, one who integrates much that is feminine. I would argue this is more apparent from his psychology than his outward appearance. But let’s begin at the beginning and examine that appearance over a chemin de fer table in Dr. No.

Using Walt Odet’s four ‘trifles’ let’s look, like the film does, in extreme close-up at Bond and see where he sits on the masculine/feminine spectrum.

Carriage: Connery may walk “like a panther”, that least masc of the big cats, but we meet him from a seated position. In fact, the first thing we see of Bond is his hands clasping the shoe. If you watch Bond’s manicured hands carefully through the scene they convey both a masculine surety of purpose and a relaxed femininity, especially in contrast with the precise ‘manlier’ movements of his female opponent, Sylvia Trench. Whatever the origins of the stereotype of gay men having floppy wrists - and there are plenty of theories, going back to Roman times - it was well-established by the time of Dr. No. This carries through to all of Connery’s Bond films, memorably reaching its apotheosis in the pre-titles sequence of Diamonds Are Forever: When asked to put his hands in the air, Connery does so with the floppiest of wrists.

When Bond does eventually stand up and start moving around, we get the iconic panther-like walk but, while collecting his winnings he leans casually against the cashier’s cage. Erect posture and leaning forward are body language traits commonly associated with Alpha Maleness. By leaning backwards, and supporting himself with the furniture, Bond is signalling to Trench that he recognises and respects her sexual potency. Neither character is diminished by this. It’s an intensely sexy scene. As Susan Sontag observed: “What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine; what is most beautiful in feminine women is something masculine.”

Manner of speech: Although the famous formulation of “Bond, James Bond” originates in Fleming’s books, it’s curious that - on film - it begins with a woman. Bond mirrors Trench (“Trench, Sylvia Trench”). A recent article in Elle reported on research that women are more likely than men to introduce themselves to someone they don’t know using just their first names, something the editor-in-chief decried as a symptom of women’s self-doubt. Trench has not a scrap of doubt and, perhaps taking her cue, Bond mirrors her masculine way of introducing herself.

Perhaps having a female screenwriter was something to do with it. Johanna Harwood is finally getting the recognition she deserves for her contribution in getting Bond off the ground. Involved at various stages, it’s not clear which parts she wrote but, according to the interview she gave to Robert Sellers in 2019, she had the final say after various others - all men - had mucked around with it. Sellers also claims she wrote the very first version of Dr. No, bookending the script’s genesis. She is widely credited with taking dialogue and situations wholesale from Fleming’s book which other writers found ‘too feminine’. Whereas several of the male screenwriters wanted to make Bond like a more stereotypical movie tough guy, Harwood kept going back to Fleming. Without her, we probably wouldn’t have the masculine-feminine Bond we enjoy today. Anyone familiar with the film industry’s gender pay gay (more like a chasm) will not be surprised to learn that Harwood’s colossal contribution to the series was not matched by her salary. Dr Llewella Chapman has discovered (from the original budget documents in the Film Finances Archive) that Wolf Mankowitz (uncredited) was paid £7000, Richard Maibaum £5100, Berkely Mather £1000 and Harwood only £300.

In Some Kind of Hero, Ajay Chowdhury and Matthew Field maintain that Fleming had the idea to give Bond a half-Scottish origin prior to the casting of Connery. Even so, when reading Fleming’s books, I find it impossible to hear Bond speaking in anything other than the accent associated with the British upper classes - Received Pronunciation (RP), or BBC English. While not a member of that class himself, Bond moves effortlessly in those circles. No wonder Ian Fleming’s first choice to play Bond was RP-accented David Niven. The film Bond we got has a recognisable Scottish burr from the very beginning. Connery suppresses this working-class associated accent to varying degrees across his tenure as Bond which, in itself, lends his interpretation of the character a queer vibe: lots of gay people who have a stereotypical gay voice try to suppress it in certain social situations. ‘Gay voice’ is a complex phenomenon and still under-researched, but most studies suggests gay men unconsciously copy sounds more commonly heard in women’s speech, perhaps as a way of signalling their difference to other men. Perhaps it has evolutionary origins: it helps us find our tribe. But many gay men find their voices ‘give them away’ and it can be a source of shame.

One of the sounds which is typical of ‘gay voice’ is a more prolonged use of sibilant ‘s’ sounds (“Yassssss queen”). Funnily enough, it’s not that different phonologically to the ‘s’ we associate with Sean Connery (“Yessssshhh”). If you try saying both of these and pay attention to what your tongue is doing, you will notice a small difference. With the gay ‘s’ you will find the very end part of your tongue is close behind your teeth (at the alveolar ridge) and letting air hiss past. When you do Connery ‘s’ you will find roughly the same but with the next part of your tongue rising upwards (to the palate). This changes the air flow and turns a gay hiss into the distinctive Connery ‘sshhhh’.

Although Connery’s variant of the Scottish accent is uniquely his, a less exaggerated ‘‘sshhhh’ sound has been associated with Scottish working class men, another group which, like gay men, can be socially stigmatised. The difference is that they emphasise the ‘s’ sounds when they want to assert their masculinity whereas the gay ‘s’ sound is used to indicate femininity. Phonologically, though, there’s really not that much in it.

Connery never entirely represses his Scottish accent in his Bond films. Although present in Dr. No it is not as flaunted as it is in later films where Connery was perhaps asserting his own working class Scottish roots and kicking back against a role he felt increasingly at odds with. It also makes the character appear to be something of an outsider. Memorably, while posing as a low-level health and safety officer Klaus Hergersheimer in Diamonds Are Forever, Connery switches up his Scottish accent to tell the snooty Dr Metz: “There's no reason to run down the little people”.

Dress: More so than his voice, it was Connery’s wardrobe that effected his transformation into Bond. And it is - to use a somewhat old-fashioned euphemism for gay men - ‘affected’.

Taken under the wing of director Terence Young, Connery had the full-on Pygmalion/My Fair Lady treatment, with Connery in the role of the Cockney-accented working-class flower girl, and Young as the upper-crust phonetics professor determined to convert her into a proper lady. Both versions of the story come with a rich queer subtext (the musical even features a song “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?”).

Midway through Dr. No, Bond tells Felix Leiter he was fitted for his suits in Savile Row - as if we needed to be told. Even less-savvy dressers such as myself know as soon as we see Bond that he cares about his appearance and only wears the best. As well as being a literal place, Savile Row is a metonym for quality clothing. Technically, his suits in Dr. No were from the tailor Antony Sinclair just off Savile Row. And his cocktail-cuffed shirts came from Turnbull & Asser, on nearby St. Jermyn Street. A 2019 GQ article noted that the aforementioned style of cuff “sneaks a flamboyant grace note into Bond’s otherwise very straight wardrobe”. The cocktail cuff, like Bond, is an intermediate between two extremes. They avoid both the potential overdressinessed femininity of cuff-links - which he wears in this introductory card game scene but not later on - and underdressed masculinity of buttons.

Of all the real-life famous tailors from Savile Row, few (that we know about) were actually gay. Tommy Nutter, the ‘rebel tailor of Savile Row’ is a notable exception. He was at the epicentre of Swinging London in the 1960s and dated the best friend and assistant of Brian Epstein, the manager of the Beatles, a gay man himself. Even so, the stereotype associated with well-dressed men - and the men who dress them - appears to be here to stay. Some well-dressed men are still regularly asked if they are gay, whether they are or not. While it is now more difficult to draw a dividing line between what clothing reads as gay and what reads as straight, we have also grown accustomed to dressing more casually in general. It’s swings and roundabouts, with the result that gay men are still, according to gay commentators like Paul Burston, seen as the arbiters of good taste. The whole premises of TV shows like Queer Eye rely on this entrenched assumption. So what might we assume of Bond, an impeccably well-dressed man frequenting a casino - a male-dominated space - until the early hours of the morning?

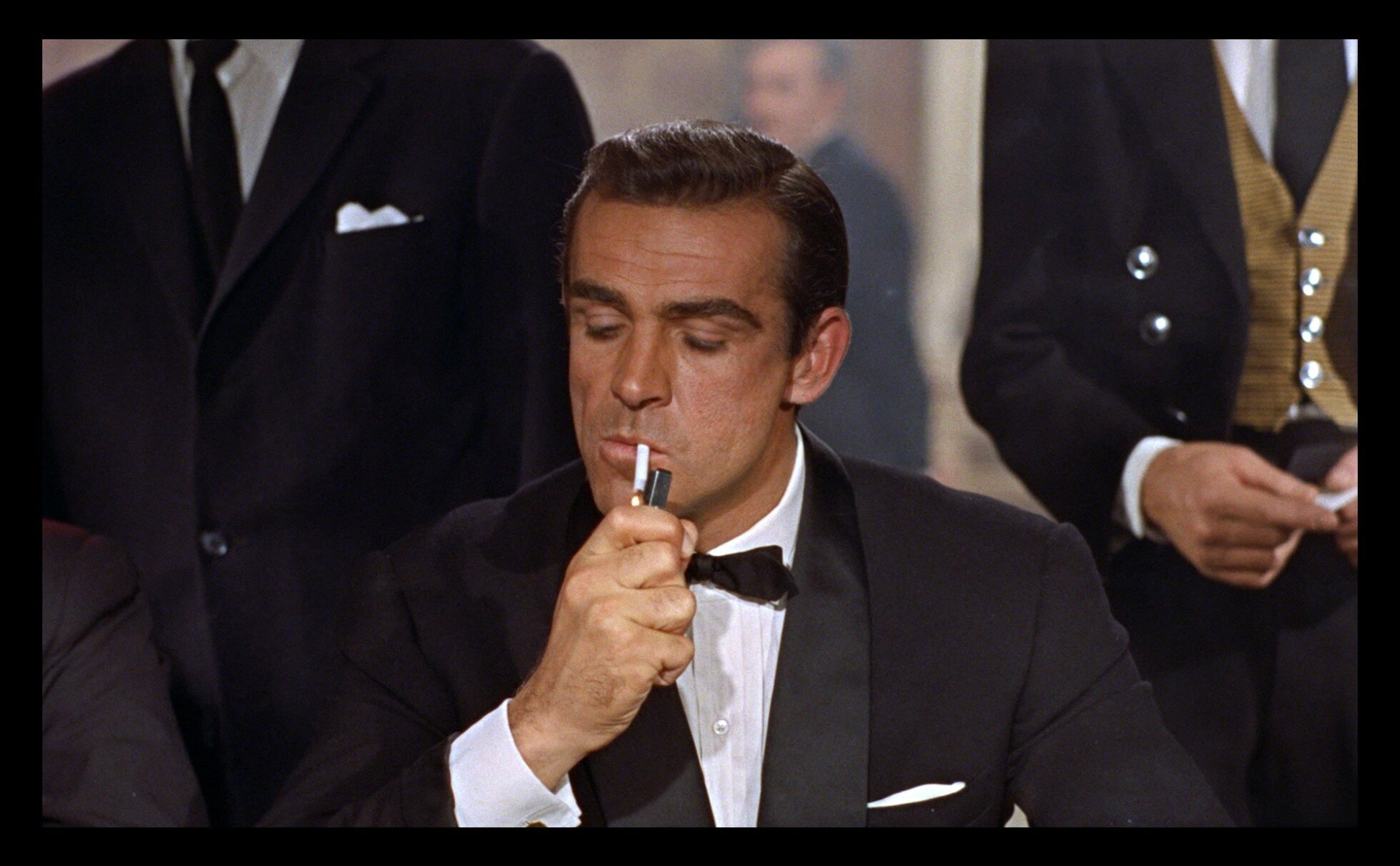

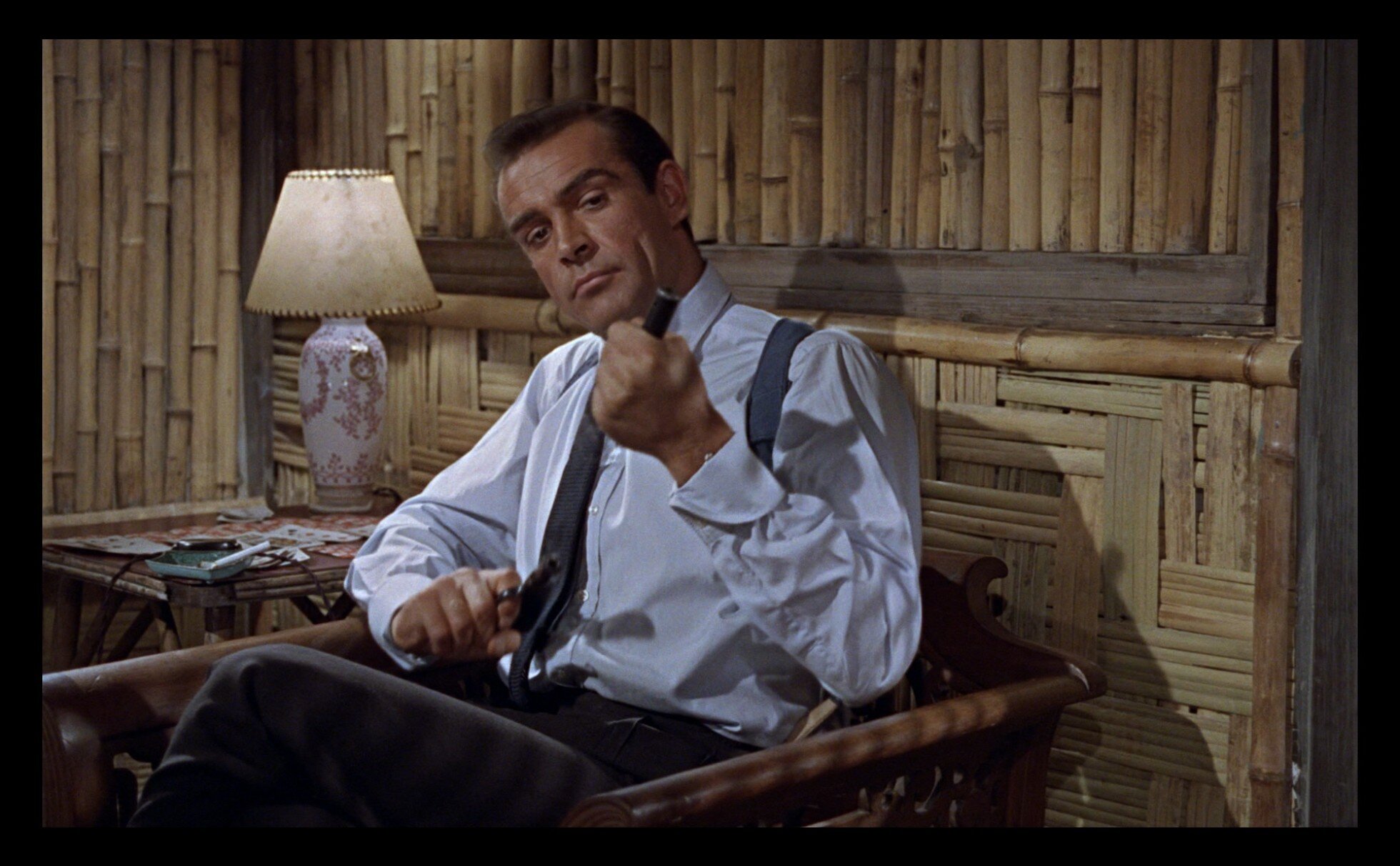

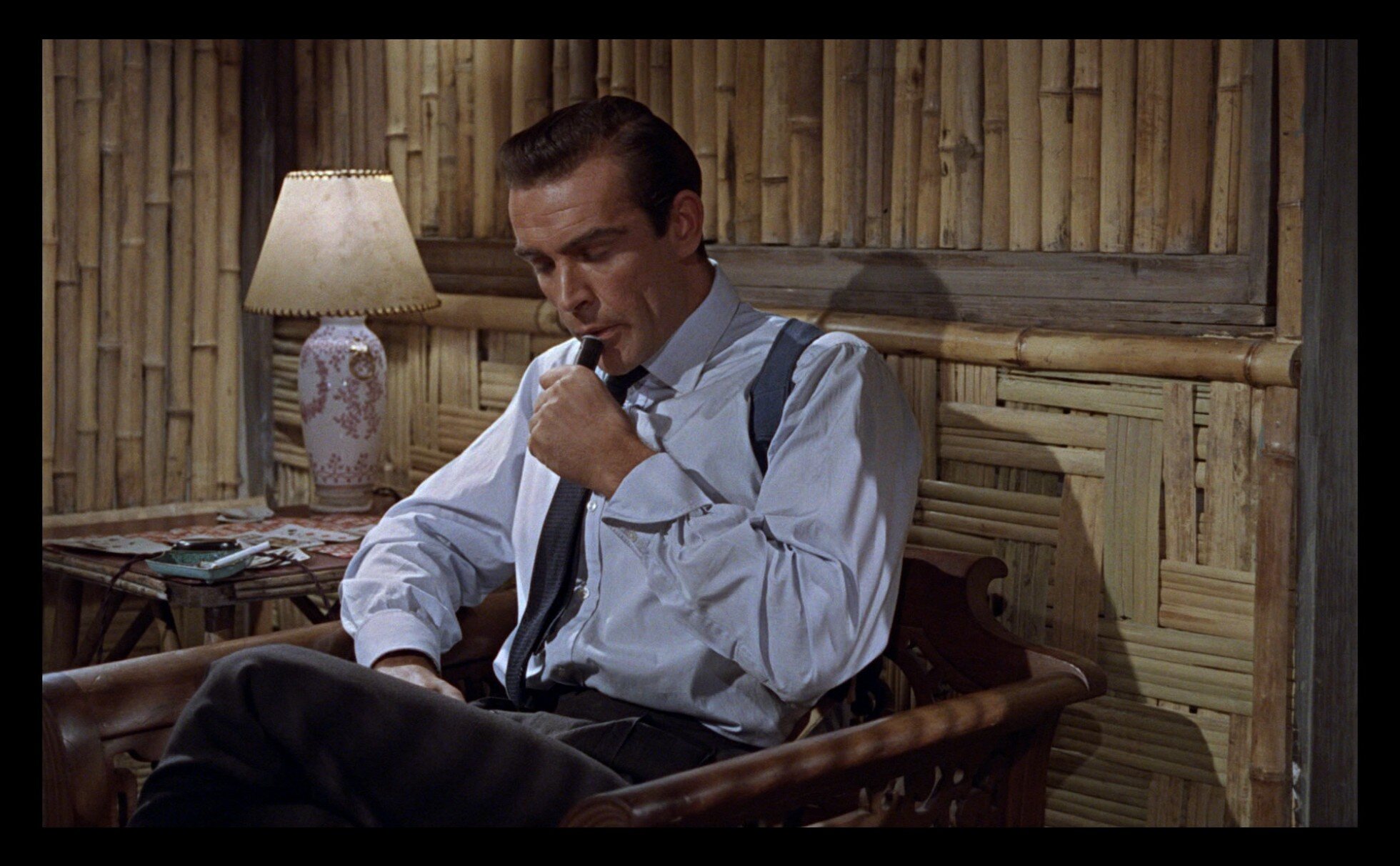

Ornamentation: Cultural historian Sir Christopher Frayling observes that a great deal of Bond’s characterisation relies on his accoutrements. Whole websites are dedicated to the things in Bond’s life we can acquire in order to emulate his lifestyle: watches, cufflinks, sunglasses, luggage, perfumes, tie clips, cigarette cases... and lots, lots more. This introductory scene is fairly restrained, but watch how the camera lingers on his cigarette case and lighter: the whole act of selecting and lighting a cigarette is festishised.

The cultural meaning of smoking has changed a lot in the last century, going from a sign of socially-desirable masculinity in the 1920s to some today arguing it makes them pariahs if they choose to continue smoking. On film, cigarettes are frequently used to represent sex acts, a form of sublimation especially common in film noir, which had only recently fallen out of fashion when Dr. No was made (the classic noir period usually ends around 1959). Dr. No continues the noir tradition, with Bond and Trench’s badinage and card game a sort of foreplay. And yet, like the chain-smoking femme fatales of noir, here it’s Bond who is smoking the cigarette. Am I reading too much into it? Possibly. In 1962, men as a whole smoked more than women so it was still a predominantly masculine thing to do. And I’m always mindful that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar (a phrase attributed to Sigmund Freud, although he probably never said it). However, smoking has, for a long time, been disproportionately common among LGBTQ+ communities, even if it took until the 1990s for tobacco companies to cotton-on to the fact and start targeting adverts specifically at them. I grew up in a household where my mum smoked and my dad didn’t, reinforcing the feminine association I had with smoking. For this gay male viewer, Bond removing one of his custom-blend cigarettes (feminine) from his gunmetal (masculine) cigarette case is an affected action which epitomises his gay sensibility.

Gay men are more than a collection of superficial ‘trifles’. But taken together, such things are usually enough to set off our ‘gaydar’, the instinct we have for spotting another of our kind. Although it’s also worth pointing out that human beings’ pupils dilate whenever we find someone attractive so this is another sign, albeit one that is mostly read by our subconscious, unless you know what you’re looking for - which you do now! (You’re welcome!)

So who you’re attracted to sexually is a part of it, along with the way we walk and hold ourselves, how we sound when we open our mouths, what we wear and the little luxuries than ornament our existences.

But what about who we love? Or if we’re even capable of love?

A four letter word

“Do you have a woman of your own?” Honey asks Bond, not long after meeting him.

It’s one of the most revealing exchanges in all of the Bond films: revealing of Bond’s gay sensibility that is. Calling it an exchange is a bit of a misnomer: Bond doesn’t supply a response to Honey’s question. He’s saved just in time by Quarrel getting his attention.

How we interpret Connery’s reaction depends a lot on our own attitudes and life experiences. This line always makes me think of those times when someone asked me if I had a girlfriend and I would fudge a response or change the topic of conversation.

But is this what was intended?

Six decades down the line, we are all now so familiar with Bond as a prolific bed-hopper, we might be inclined to read Connery’s reaction as boastful. He doesn’t just have A woman, we might think, with a smirk, but several. Even if this was the first Bond film we had seen we have, by this point in the story witnessed him having sex with two women. Consider though, that Sylvia Trench was almost an inconvenience to him: he was in a hurry to catch his flight. And he sleeps with Miss Taro to keep her busy while waiting for a government car to come and pick her up. Both times Bond is on the clock - quite literally. In both encounters, he checks his watch. Sex is reduced to something functional, a transaction to be completed as swiftly as possible. According to Terence Young, the second time he checks his watch - with Taro - got one of the biggest laughs in the picture.

But remember: this first Bond film was intended to have a serious tone (see Camp, below). I’m therefore not convinced we can support the idea that the “Do you have a woman of your own?” scene is merely intended to be a joke about Bond’s promiscuity. To me, it looks as if Connery is being tight-lipped because he knows Bond would rather not answer the question. He’s embarrassed by the truth. It’s not knavishness we read on Connery’s face but shame. Bond doesn’t have anyone. He may sleep with a litany of women but he’s incapable of forming a meaningful attachment with any of them.

That gay men have random hookups in lieu of relationships is yet another stereotype and, as such, should be treated with extreme caution. As a happily married man who has been with their partner for more than a decade I know it’s not the case for everyone. But I also spent my adolescence and my early twenties thinking I could never be in love with a man. And I didn’t want to be in love with another man. Even the thought of doing the romantic things we see straight couples doing from a very early age - holding hands, kissing - repelled me. I recognise now that this was internalised homophobia, one of the many hurdles gay men face in coming around to the idea that they can love and be loved in return. It’s a phenomenon familiar to many gay men, and one that is much written about. The consensus is that, while it’s no longer as difficult to find a sexual partner in the age of dating apps, it’s just as hard as it ever was to find and stay in a long-term relationship.

Genital combat

In his highly influential Eight Ages of Man, published in 1950, psychologist Erik Erikson identified the stages humans go through from early infancy onward, to emerge as healthy adults. Erikson claimed that all of us need to reconcile the conflict between needing to be our own person and forming intimate connections. In the stage prior to forming these connections, sex was a tool for finding out who we are. The sex we had in adolesence/early adulthood, “dominated by phallic or vaginal strivings” was “a kind of genital combat” - which is accurate a description of Bond’s couplings as I’ve ever heard.

Based on Erikson’s model, Bond’s development into a healthy adult has stalled. This is not quite as true for the Bond of Fleming’s books as it is for Connery’s portrayal of him in Dr. No. When Fleming was interviewed in August 1963 for BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, he felt compelled to defend his character’s bedroom antics. Representing the more prudish views of middle class Britain, presenter Roy Plomley playfully provoked Fleming by stating that “Bond takes sex almost as casually as he takes a drink”. Fleming’s response was somewhat defensive: “Well, he has one girl per book, approximately. And that’s one a year. He’s a bachelor and he moves around the world pretty rapidly and, erm, I don’t see any great harm in that, myself.”

Perhaps Plomley was conflating the Bond of the books with the character fronting the first Bond film (From Russia With Love was still two months away from release at the time of the interview). In the film of Dr. No, Connery engages in ‘genital combat’ with three women, compared with the book’s one. Even so, Plomley was on to something which is heightened by Connery bringing an adolescent impishness to the character which is not in the novels. It makes us think that, like an alcoholic drink, a woman is an entirely consumable and expendable pleasure. The ‘manolescent’ Bond simply isn’t mature enough to take anything more seriously.

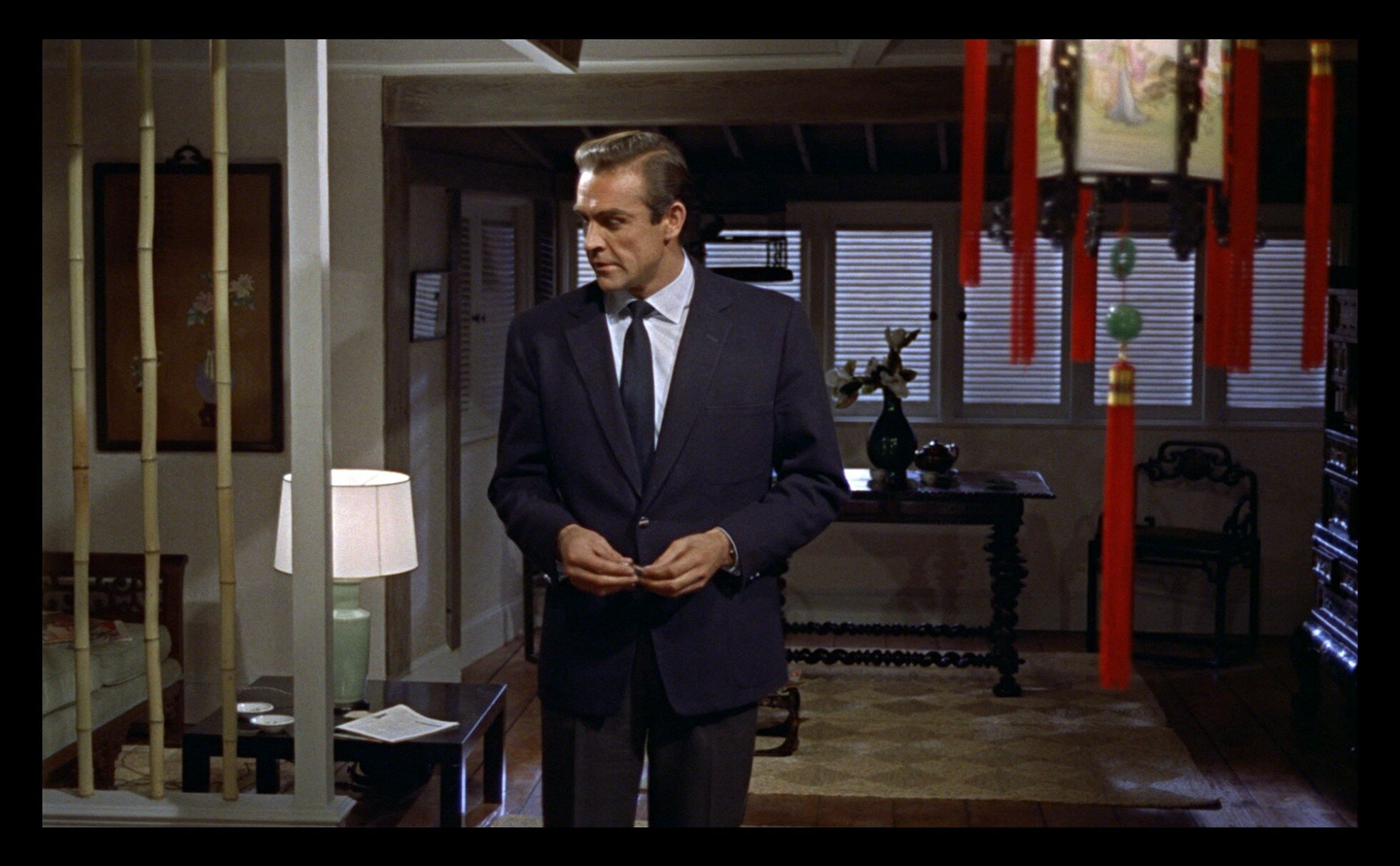

In Dr. No, we get a rare glimpse of Bond’s apartment and it always looks to me like a boy’s bedroom. With its pictures of brightly-coloured antique cars on the walls it’s definitely in ‘man cave’ territory. Bond’s immaturity is a character trait which is consistent throughout the series and remarked upon in the scenes with Q: in Octopussy, for instance, Q chastises Moore’s Bond for his “adolescent antics” and in Tomorrow Never Dies he tells Brosnan’s 007 to “grow up”, an idea which is picked up in Bond’s own dialogue when he later tells Wai Lin he never grew up at all. Even Dalton gets paid a visit from ‘uncle’ Q while on mission in Licence To Kill. And although the age dynamic is reversed with Whishaw’s Q, Craig acts like an ungrateful child in Skyfall when he doesn’t get what he wants for ‘Christmas’.

Other games

Had the Eon film series began with the first book, Casino Royale, we may have an explanation for Bond’s inability to grow up and form a relationship: the trauma he experienced following the betrayal of Vesper Lynd. But shorn of this in Dr. No, essentially going into the character cold, we’re left wondering why he’s incapable of love.

In lieu of anything lasting, Bond has a string of casual sexual partners. Building on Erikson’s idea of “genital combat”, Walt Odets uses the term “sport sex” to describe sexual acts with are purely physical, where any vulnerable emotions are strictly off the table. That Bond thinks of sex in gaming terms is revealed shortly after his ‘combat’ with Trench over the card table:

Bond: Tell me, Miss Trench, do you play any other games? Besides "chemin de fer"?

Trench: Hmm. Golf… amongst other things.

So-called ‘meaningless’ sexual encounters are never meaningless according to Odets. Instead, they are “almost always a search for emotional connection to another man, but one conducted without the developmental experience that would facilitate and support the process”. In other words, gay men don’t know how to love because they haven’t been taught how to. They haven’t been shown any examples. They haven’t gone through the same developmental stages of forming a romantic attachment with someone in adolescence, at least not openly. And concealing a crush on a boy in your teenage years is more likely to result in self-shame than learning an important life lesson that will allow you to form meaningful relationships later in life.

Most gay kids simply don’t get the opportunity to learn what romantic love is or looks like. Think of all those times - even before adolescence - when we overheard parents, family members and friends refer to our possible romantic attachments, now and in the future. If you’re a non-queer person reading this, you probably don’t even remember specific occasions because they just seemed ‘normal’ to you. But I’m willing to bet all of you reading this who are predominantly attracted to the same sex remember those times a grown-up asked you if they had a girlfriend (if you were a boy) or a boyfriend (if you were a girl), or if you were likely to have one in the near future (bisexual people were of course, as usual, invisible in such conversations).

Those of us who experienced such incidents probably have them burned into our memories, perhaps blurred together as one cringe-inducing composite. This is certainly true in my case. You might also remember - as I do - the evasive responses you came up with - either pre-rehearsed or on the spot. “I’m just not into dating.” “There’s no one I’m really into.” “I’m just too picky.” “I’m too busy with school.” Some of us may have continued to use such excuses later in early adulthood, prior to coming out (I’ll hold my hand up here!). Some gay people may even continue to use them even after they have accepted who they are as a way of deflecting an even more uncomfortable truth: they don’t know how to love someone else.

Like a lot of gay men, I feel my own emotional development was held back merely by the fact of my being gay. I didn’t have a relationship until my mid-20s, years after most of my friends had been in several. I know plenty of gay people my age (headed towards 40) who have still not had what they would label a ‘relationship’. There are some that say striving for ‘the one’ is a homonormative trait that devalues queer identity. I’m not saying people have to form one attachment with one other human being. I know some very happy gay people who have multiple long-term partners. Another unshakeable stereotype, popular with straight men in particular, is that gay people have so much freedom because they don’t feel as much pressure to ‘settle down’ with ‘the one’. But the heartbreaking reality for many gay men is that they, as Odets puts it, “find themselves bewildered by gay relationships, often having ongoing sexual encounters that, in the longer term, become unsatisfying”.

Boy with a toy

James Bond’s penis must be the most written about sex organ in all of popular culture. It receives its most insightful and witty treatment in Toby Miller’s essay: Cultural Imperialism and James Bond’s Penis. Miller points out that it’s not even subtext: “The gun as phallus is encoded in the textuality of Bond. It does not await the textual analyst to uncover this fact. Rather the symbolism is played with deliberately.”

If Bond ended up on a psychoanalyst’s couch and said analyst managed to get him to open up, it wouldn’t take long for discussion to centre on phalluses - in their various forms. We’ve already dealt with cigarettes. Unlike cigarettes (and cigars), a gun is rarely just a gun in Bond. But what does 007’s ‘gun’ say about his integration of masculine and feminine qualities?

The phallic shapes of guns speak to men’s desire for - and hang ups about - sexual potency. And this includes gay men. While shooting things is often seen as a straight male pastime, gay people love guns too. We are still, after all, fighting feelings of inadequacy. What better way to do this than by firing off a few rounds? There’s a reason why a best-selling brand of sex lubricant marketed at gay men is called ‘Gun Oil’ (other products in the range are subtitled ‘force recon’, ‘loaded’ and ‘tactical cream’, stretching that metaphor).

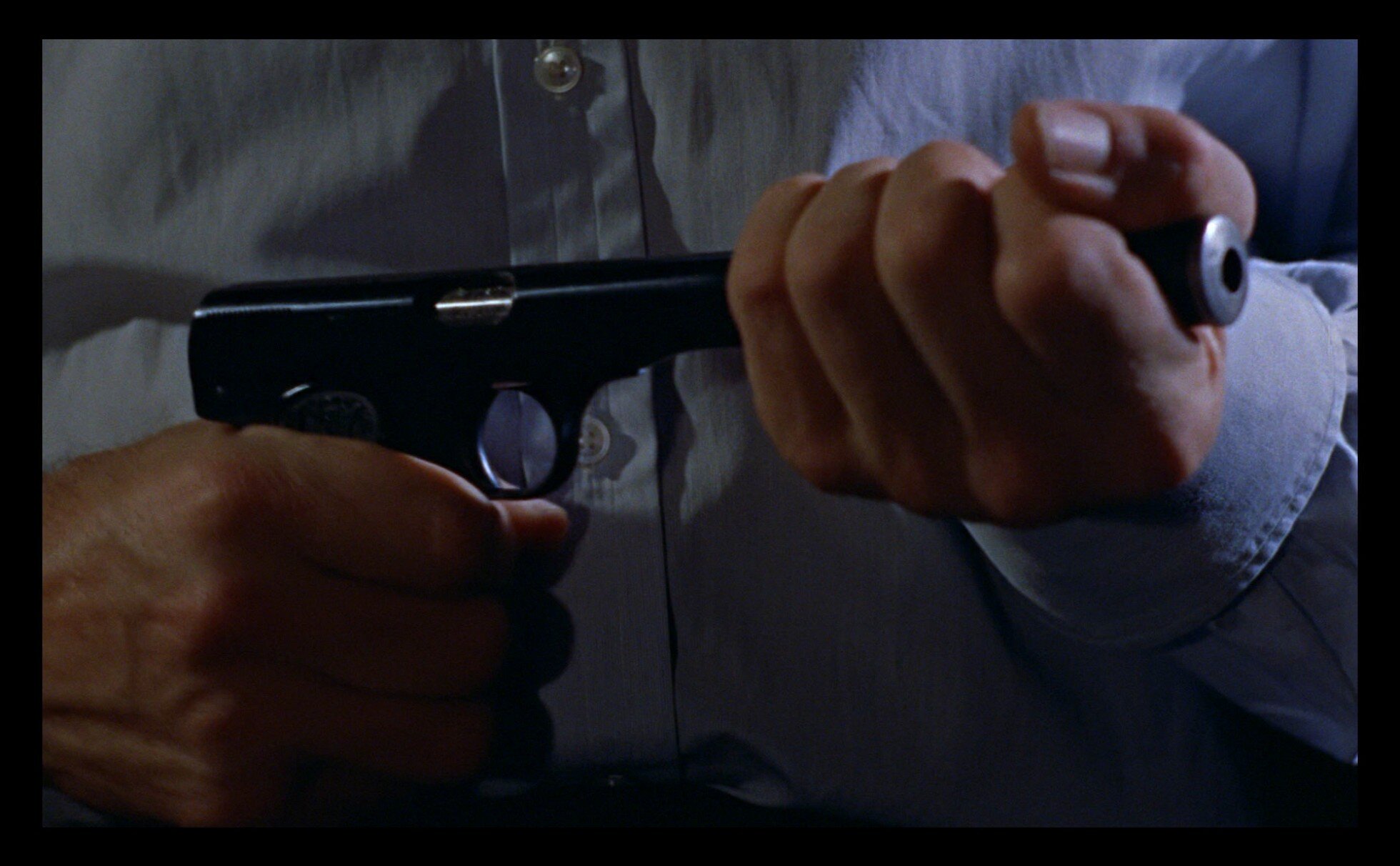

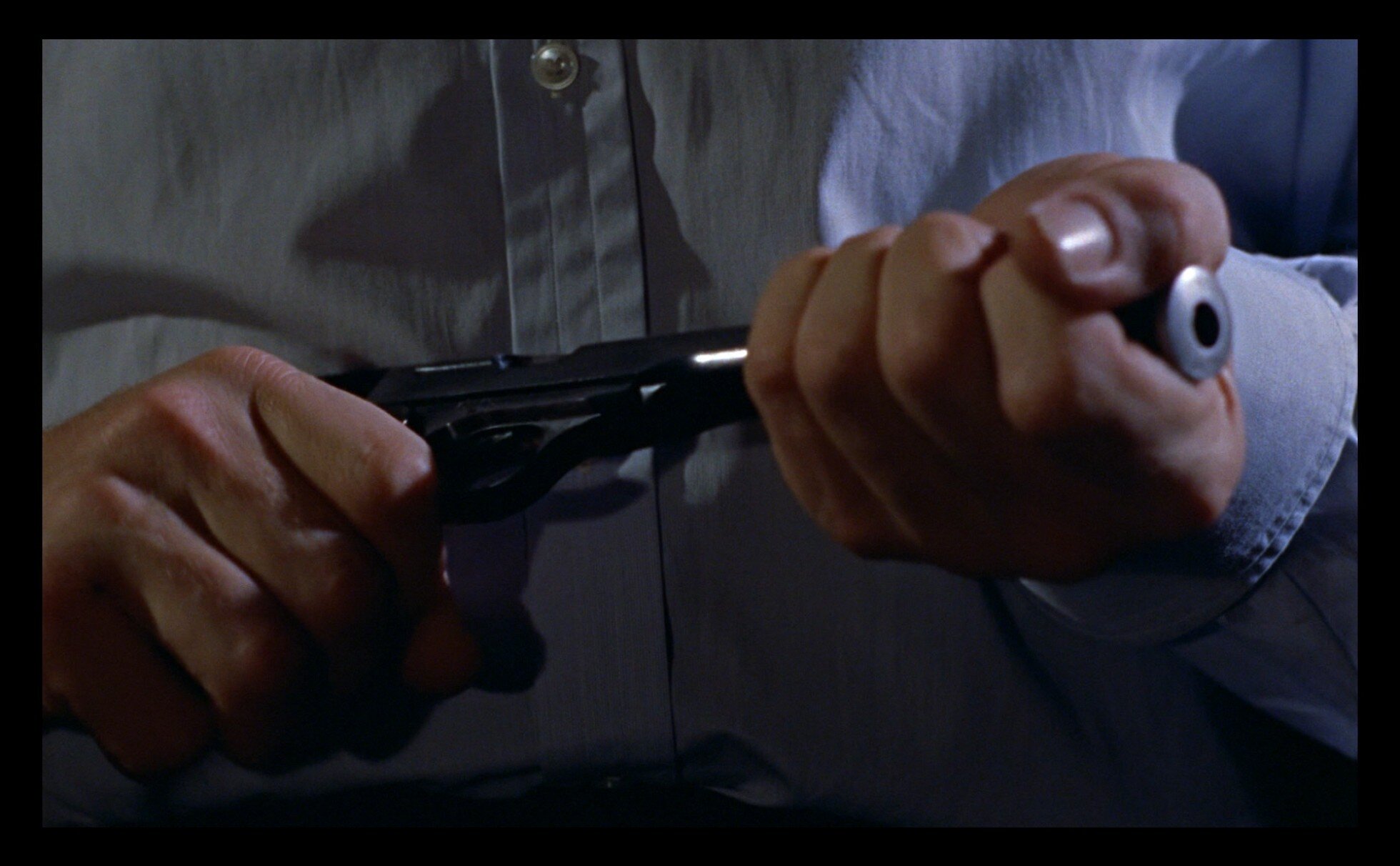

Dr. No is the Fleming book where Bond gets issued with the gun he’s now synonymous with: the Walther (although it’s not the PPK model of later films). In the previous book, From Russia, With Love, his otherwise trusty Beretta gets jammed and he ends up almost killed by Rosa Klebb’s venomous shoe. While an incident that put Bond in the hospital for six months is alluded to in the film of Dr. No, the Klebb confrontation hadn’t happened yet in the film continuity, thereby making the scene where the unnamed Armourer (named Major Boothroyd in the book) berates him about his Beretta more conspicuous. What are we to think about a man who, until he’s issued with a replacement, was happy carrying around a “nice and light” Beretta only suitable for a “lady’s handbag”? As the Armourer talks about the Beretta he weighs it up and down with his hand, as if weighing up a part of Bond’s anatomy and finding it wanting.

We are also told that the Beretta “jammed”, further emasculating 007. In place of the Beretta, Bond is made to use the Walther, which has a “delivery like a brick through a plate glass window”. Some have taken this to show that Bond is overcompensating for something, but he could have ended up with something far more imposingly masculine. In an amusing featurette made for the BBC during the filming of Goldfinger and fronted by an appealingly floppy-handed Sean Connery, Bond’s guns are pored over. The real Boothroyd - the gun aficionado whose letter to Fleming included the lady’s handbag sentiment - demonstrates the stopping power of several guns in turn: the Beretta, the Walther and, finally, the .44 Magnum, later made famous by Clint Eastwood in the aggressively macho Dirty Harry series (and emulated - briefly - by Bond in Live And Let Die). The Walther’s power sits somewhere in the middle of these two extremes, making it masculine, but not to an excessive degree. No wonder, according to Toby Miller, “Bondian sex, fairly progressive for its day, was too much for US critics” with Bond “frequently criticized as a wuss”.

Bond is wounded by having to let go of the Beretta, a direct order from M. Does he feel shame because of the ‘lady’s handbag’ remark? Does he feel he’s let himself down by wanting to hang on to something considered womanly? In the novel’s version of this scene, things go well beyond a sentimental attachment to an inanimate object. Fleming devotes nearly an entire page to Bond morosely looking back over his “fifteen year marriage” to the weapon. He fondly remembers oiling the gun, packing the bullets into the magazine before “pumping the cartridges out on to the bedspread in some hotel bedroom”. After this ritual, Bond would give the gun “the last wipe of a dry rag”, holster it and, finally, “pause in front of the mirror to see that nothing showed”. You don’t need the insight of a psychoanalyst to know there’s more going on here than just a man swapping his gun for a better model. That gun was the most lasting, most meaningful relationship of his life.

Bond leaves M’s office saddened, but armed and ready. ‘Genital combat’ awaits.

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

Upping the number of notches on Bond’s bedpost was not the only thing the filmmakers did in an attempt to make Bond more ‘red-blooded’ than he was in the book. He also gets to flirt with M’s secretary, Moneypenny. It’s a different relationship in the books where Moneypenny is presented as very attractive but completely unobtainable. For her part, the Moneypenny played by Lois Maxwell makes it clear she IS obtainable “given an ounce of encouragement”. But Bond friendzones her by talking shop: “I would [take you out to dinner], you know. Only M would have me court-martialled for illegal use of government property.”

In some ways, M himself is the Bond series’ personification of the capitalist society which has been driving heteronormativity for centuries. The ideal, ‘normal’, socially-desirable setup is a monogamous marriage between one man and one woman with the woman freed up to look after the 2.4 children (unpaid labour) while the man goes out to work and keeps the wheels of the economy turning. And yet, on the other hand, M himself is another of those confirmed bachelors we’ve heard so much about (wink wink). Bond’s boss also prefers images of vehicles on his wall to people, except in his case it’s ships rather than cars. Unlike his best agent, M has a disdain for staying out with other men all night (“When do you sleep 007?”) although he doesn’t seem to do much in the way of sleeping himself. Nevertheless, there’s immediately something intensely queer about M and his relationship with 007. Perhaps he’s jealous of Bond’s nighttime cavorting? It would have been so easy for Fleming to give M a wife, which may or may not have shut down some possibilities. Kathleen Jowitt has argued that Fleming depicts M and Bond’s relationship like a marriage, something that carries on over to the film of Dr. No. Knowing Fleming’s own hostile feelings about marriage lends weight to the argument. Fleming also worshipped at the feet of older male mentors which Fleming biographer Andrew Lycett puts down to reasons which are “psychologically complex”. I’ll say!

Also complex is Bond’s relationship with Quarrel. It would be easy to dismiss the most problematic elements (“Quarrel, get her” / “Fetch my shoes”) as products of their time or reasons to ‘cancel’ the film. But both approaches are too reductive and risk causing us to miss the wood for the trees. We would more fruitfully examine their relationship as the latest iteration of something which has existed for centuries and still requires our attention. As Meg-John Barker observes:

“As with capitalism, colonialism relies on seeing some bodies and lives as less valuable than others in order to justify colonizing - and often enslaving - others. Like women and children, colonized people were often regarded as property belonging to white men.”

This hasn’t gone away - just as the marginalisation of queer people has not gone away. And colonialism and queerness are inextricably intertwined. Anyone who is not white, male, straight and able-bodied is Other.

Just as Moneypenny is “government property”, Quarrel’s relationship with Bond is based on the assumption - largely unremarked upon in the film - that the former is submissive to the latter. But to what degree? Quarrel refers to Bond as “captain” throughout, signifting their difference in social-standing and echoing their colonial antecedents. The first time Bond and Quarrel meet in his novels, Fleming frames the relationship as “that of a Scots laird with his head stalker; authority was unspoken and there was no room for servility”. In the novel of Dr. No, Fleming explicitly invokes the character of “Man Friday” in relation to Honey’s manner of dress to indicate that she is ‘uncivilised’. It’s possible Fleming also had the character of Friday, from Daniel Defoe’s novel The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe and its sequel, in mind when he conceived of Quarrel.

Defoe’s eponymous character, Crusoe, a white man, forms an attachment with a black ‘native’, who he names Friday. It’s an unequal relationship, similar to that Bond has with Quarrel. While Quarrel is a very capable fisherman, he is infantilised through his persistent belief in local superstition, in contrast to the entirely rational, worldly Bond. Similarly, Friday has to be ‘civilised’ over the course of his adventures with Crusoe.

In the second of Defoe’s Crusoe novels, Friday is killed after Crusoe orders him to go ahead of him and see what some other ‘natives’ are up to. After exposing themselves to Friday (showing their “naked backs” we would write as ‘mooning’ nowadays) they fire arrows into him. Inconsolable, Crusoe massacres the ‘natives’, enters their lair and vandalises their sacred idol. While Defoe’s books are a satire on capitalism, several academics have also detected a homoerotic subtext. In fact, the two go hand in hand: an attack on heteronormativity is an attack on the straight, white, male hegemony of capitalism. There was even a parody, The Secret Life of Robinson Crusoe, published the same year Dr. No was released, which pushed the homoerotic elements to the fore, although they’re pretty hard to miss in the original texts. Friday being penetrated by arrows makes him a gay martyr along the lines of Saint Sebastian, who was also penetrated by arrows (memorably homoeroticised in Derek Jarman’s 1976 film).

Quarrel’s death, not by arrows but by flamethrower, steels Bond’s determination to defeat Dr. No, just as Robinson Crusoe wreaks vengeance on those who took away from him the only person he cared about.

This isn’t to brush under the carpet the sometimes uncomfortable master-servant dynamic between Bond and Quarrel. Contrast this with the Quarrel, Jr. character in Live And Let Die, eleven years later, who Bond tell us shares his hair brush. While not exactly equal, there’s a more fraternal feeling to their relationship in Live and Let Die than the one in Dr. No.

Fans of the Fleming novels know that the character is the same person in both the books of Dr. No and Live and Let Die. It’s just that by the time the character was needed for the film of Live and Let Die, he had been already been killed off because the books were shot out of order. Another character, Sharkey, stands in for Quarrel in the film Licence to Kill, which draws heavily on the book Live and Let Die. Sharkey also, unfortunately, dies.

Fans of the books will also know how homoeroticised the relationship is between Bond and Quarrel, especially in their first appearance together, with Quarrel giving Bond very intimate rubdowns. Sexual conquest has often been used as a metaphor for colonialism in fiction, reflecting the often uncomfortable reality. It’s sometimes a colonised woman, being fought over by male representatives of foreign powers (see for instance, Graham Greene’s The Quiet American). Accounts of historical male to male colonial sexual conquest are understandably harder to track down, but some first-hand accounts have survived. A lot of today’s sex tourism is arguably a modern manifestation, with rich European and North Atlantic men in search of the exoticised Other.

Many of the aspects of the Dr. No novel that we would recognise as racist today were toned down in the film. And while the imbalance in power is inherent in the Bond and Quarrel relationship, there’s nothing overtly sexual in the film, despite their initial meeting sounding like a coded exchange of the kind gay men might have used to reach a mutual understanding and find somewhere more private to have sex (see my queer re-view of The Living Daylights for the history of this). Unlike some of the allies Bond will team up with later on, whose deaths are so telegraphed that they might justifiably fall into the ‘sacrificial lamb’ story trope category, there’s a sense of genuine emotional connection with Quarrel, closer to anything he achieves with a woman in this film.

The only male rival Quarrel has for Bond’s affections is Felix Leiter. The first thing Leiter says to Bond (while standing behind him with his gun poking into his back) is “Gently, bud. Gently. Let's not get excited”, setting the flirtatious tone which is a hallmark of all the best Felix Leiter portrayals to come. As in many of the stories, Felix is feminised by not actually getting to do all that much besides keep the USA’s end up. He looks really cool though (and that counts for a lot, right?), immediately making an impression with his cat-eye sunglasses. Bond fashion expert Matt Spaiser notes these sunglasses “have since become primarily worn by women”. Fashion, you are a fickle creature.

While the extent to which Fleming resembled his fictional creation is often overstated, his preference for male friendships over relationships with women is definitely something they have in common. Matthew Parker, whose book explores Fleming’s life in Jamaica, says “he had many male friends from different parts of his life” but with women he was “distant, aloof, moody and melancholic.” One of those friends was Ivar Bryce, whose business interests informed much of the plot of Dr. No (the guano mine and bird conservation are completely excised from the film) and Bond uses his name as cover in this book and Live and Let Die. Bryce isn’t mentioned in the film of Dr. No, but another friend, John-Fox Strangways, is. Strangways, who was a significant ally of Bond’s in the novel Live and Let Die, appears in the Dr. No film and novel very briefly, being assassinated at the beginning. According to biographer Andrew Lycett, Bryce and Strangways were so close that, when staying with Fleming at his Goldeneye home, they would go swimming naked together before breakfast.

Strangways appears to have had a relationship with Quarrel similar to that of the relationship that develops between Bond and Quarrel. The photograph of the two of them that Bond finds in Strangways’ house portrays them as fishing buddies. It’s remarkably similar to a photograph of Fleming with his friend Barrington Roper. Although Fleming’s creation of Quarrel pre-dates his friendship with Roper, ruling him out as an inspiration for Quarrel’s first appearance in Live and Let Die, his closeness to Roper may have influenced Quarrel’s characterisation in Dr. No.

Shady characters: Villains

Just as fear of queer people can be used to make audiences uncomfortable, so can portrayals of people with disabilities. Sometimes the two can be brought together to heighten the sensation of Otherness. As Charlie McNabb, author of Nonbinary Gender Identities, has pointed out, “Both queer people and people with disabilities are minorities in society. To be queer and disabled, then, is a double marginalization… media portrayals of disabled people with healthy and active sexual lives are rare and somewhat radical; even more so when they do not fit into heteronormative categories.”

Being a visual medium, Cinema is especially effective at exploiting feelings of Otherness related to queerness and disability, particularly if that disability is blindness. Susan Crutchfield, who has written extensively on disability in cinema, argues that when sighted viewers see blind characters depicted on a screen, they can feel threatened. Not only might sighted viewers fear loss of sight but other things they take for granted. According to Freud, male anxiety about being castrated is on par with that of being blinded. He illustrated this by using the story of Oedipus, who blinded himself as self-punishment for murdering his father and sleeping with his mother.

Aside from Bond in the opening gunbarrel (played by stuntman Bob Simmons) and the silhouetted dancers over the titles, the three blind assassins are the first characters we see, establishing an off-kilter reality that only gets more discomfiting when we find out the three men are assassins and probably not blind after all. Being blind doesn’t preclude one being an assassin of course, as the popular Japanese character, the blind swordsman Zatoichi, attests (coincidentally, the character’s first film was released the same year as Dr. No). Even so, we are led to believe that we have been ‘tricked’ by the three assassins, just as Strangways didn’t identify them as potential threats because of their disability. There’s a bitter irony to Strangways giving them a donation moments before they shoot him dead (in the novel it’s a pointedly generous amount). Is this supposed to be his just desserts for taking pity on disabled people and underestimating their capabilities? Or is this intended to make the audience fear disabled people, especially any who are suspected of ‘putting it on’, just as queer people might be distrusted for concealing their true identities?

How we’re supposed to feel about disabilities is even less clear cut in Fleming’s books. While disabilities are regularly used to Other characters, not all the disabled characters are villains. When Felix Leiter is mauled by a shark and has his hand replaced with a hook in Live and Let Die, he is no less proficient at carrying out his work. Such a moment has yet to find its way into the films, perhaps because film is so visual and filmmakers are nervous about portraying disability and anything that is visually ‘abnormal’. I’m not making excuses here: there really is no excuse. We are yet to even have a Bond with a facial scar of the kind Fleming describes in his books for similar reasons: would the audience be able to believe that a hero with an Othering mark was truly capable? Very sad if that is the case.

Blindness and unheternormative sex go hand in hand (in a manner of speaking…). The myth that masturbating makes you go blind has been around since at least the 18th Century and was still widely believed well into the 1950s and 1960s. I can personally recall looking up ‘masturbation’ in an old leather-bound encyclopedia in my grandma’s house and it unequivocally establishing causation between loss of sight and what it termed ‘self abuse’, which was concerning reading for a thirteen year old to say the least.

Another myth which persists is the nursery rhyme Three Blind Mice being an allegory for a Protestant revolt against Queen Mary in the 16th Century. This is almost certainly not the provenance of the short rhyme:

Three blind mice, three blind mice,

See how they run, see how they run,

They all ran after the farmer's wife,

Who cut off their tails with a carving knife,

Did you ever see such a thing in your life,

As three blind mice?

If this traditional version of the song was used in Dr. No, we could credit that with contributing to the film’s castration anxiety (tails = penises). However, the lyrics written by Monty Norman for the film are more about empowering the mice to wreak revenge on the cat which has eaten the rat (presumably a rodent friend):

They're looking for the cat

The cat that swallowed the rat

They want to show that cat

The attitude of three blind mice

These three co-dependent ‘blind’ men in Dr. No are established musically as ‘mice’, a further way of dehumanising them. As if we needed another method of Othering these characters! They are already, at the very least, a triple threat: ostensibly disabled; members of a minority ethnic group (mixed race ‘Chigroes’ in the novel) and queer.

In contrast with the poor ‘mice’, Professor Dent has all the outward signs of privilege and, therefore, should be trustworthy: he’s white, English, educated, able-bodied and apparently straight. But Dent is as bent as they come. His motivation appears to be straightforward greed, with an unhealthy dose of fear of Dr. No compounding his willingness to deceive his government. This extends to attempting to kill one of their top agents, although the manner of doing so is deeply queer.

Like many characters in this story - both good and bad - Dent seeks to harness the power of nature (traditionally aligned with femininity) to do his dirty work rather than immediately launch into direct assault (which would be more masculine).

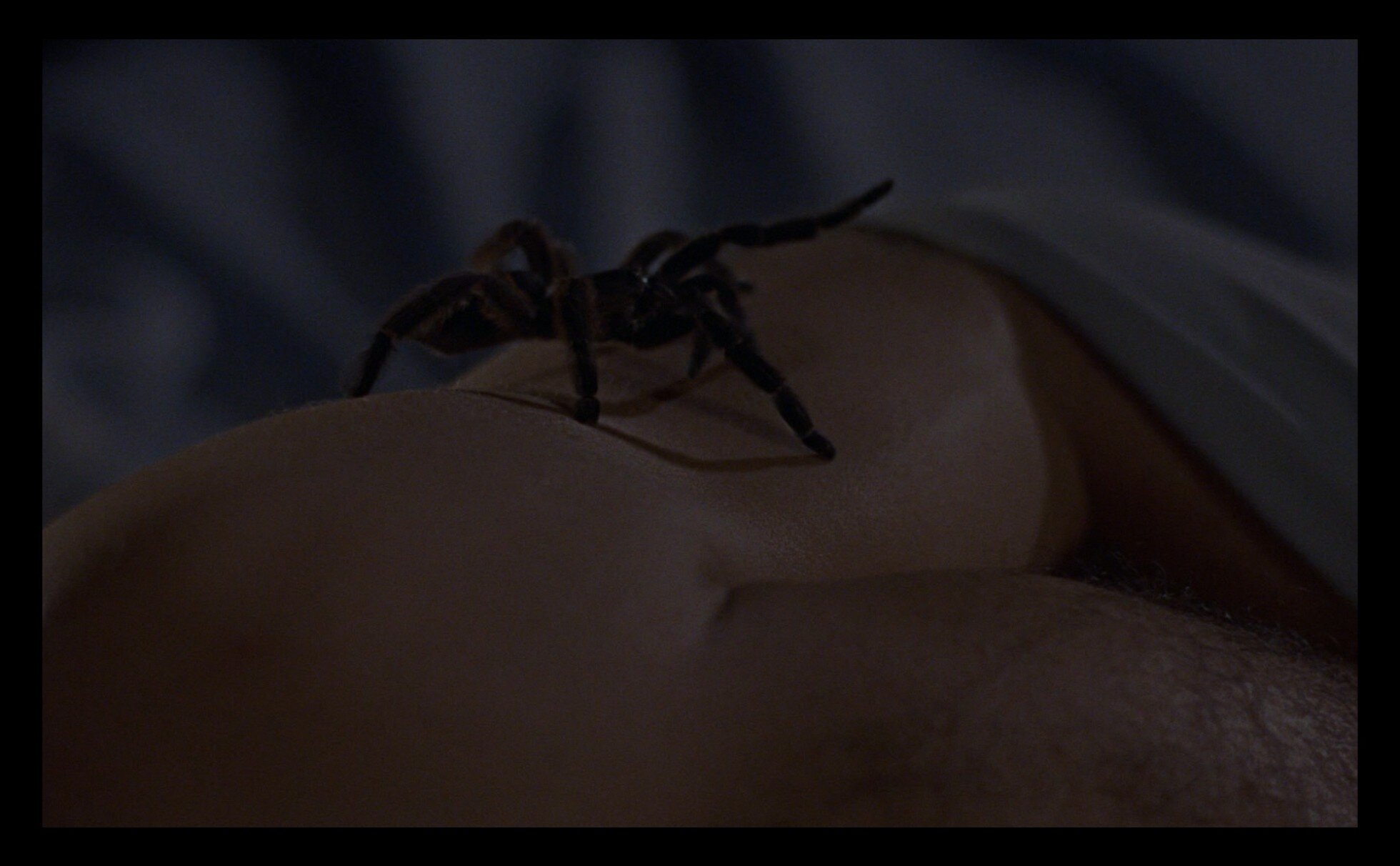

The attack by creepy crawly is one of the sequences lifted almost entirely intact from Fleming’s book (one of Fleming’s very best passages). The only significant difference is the film having a spider in place of the novel’s centipede. Why the change? Was a spider just more obviously intimidating for cinema audiences? Personally, despite being somewhat of an arachnophobe myself, the footage of centipedes I’ve watched in the course of researching this has convinced me that I would much rather have a tarantula in my bed than a giant centipede. With apologies to any entomologists reading this: those things are creepy indeed.

Illustration by George Almond for 007 Magazine

There’s a slim chance that someone on the Dr. No production was aware of centipedes’ queer connotations, at least in literary circles. The year after Dr. No was published, gay novelist William S. Burroughs published his disturbing, fractured, centipede-obsessed novel Naked Lunch. In David Cronenburg’s 1991 film adaptation, a gay character turns out to be a giant centipede who then eats the man he’s just slept with. Pleasant.

And more recently, thanks to a notorious film released in 2010, ‘centipede’ when collocated with ‘human’ has taken on a very unsavoury connotation (you know what I’m on about, don’t pretend you don’t). There is also, according to Urban Dictionary, something called a ‘gay centipede’ which I cannot define on a family-friendly website. Although I do my utmost to try to keep an open mind about any non-normative sexual practices, in this case I will just say: No. No thank you. Move along now.

And frankly, the less we say about formicophilia, the better.

The decision to kill 007 with a spider is Dr. No’s doing, but he leaves it up to Dent to decide how best to deploy the eight-legged beastie. Slipping it into Bond’s bed seems to be a sensible approach, although one that leaves an awful lot to chance. In the book, this scene is even more sexualised than the film, with the centipede seeking the warmth of his groin and Bond growing increasingly unconcerned that it will try to “crawl into the crevices”, suggesting a horror of anal intrusion. The film evokes similar horrors of the unknown, with a bulging mass moving up Bond’s body, disturbing the sheet as it goes. Connery was himself terrified of spiders, which explains why most of the shots with the spider are not Connery but stuntman Bob Simmons. It’s easy to tell which shots are Connery and which are Simmons: Simmons’ shoulders are almost completely hairless, whereas Connery’s are an impressive rival for the hairy spider’s. That the Connery was prepared to admit his fear of spiders on the Dame Edna chat show was a bold move. Good on you Sean!

The switch from centipede to spider has the happy side effect (probably unplanned) of establishing some symmetry with a moment later in the film, when Honey Ryder tells her story of killing her rapist with a (female) spider.

In one of the film’s most celebrated scenes, Dent’s own death is used to anchor the characterisation of Bond as a cold-blooded killer. After Dent has unloaded his gun into what he thinks is the prone figure of Bond (a symbolic penetration if ever there was one), 007 responds in kind. The number of shots Bond fires was censored down to just two after censors objected. Perhaps they weren’t just made uncomfortable by the cold-blooded nature of the killing but by the homoerotic implications. The scene always reminds me of a shootout in a western where posturing men challenge each others’ masculinity and battle to come out ‘on top’. Sergio Leone would push climactic gun battles to fetishistic extremes in the contributions he made to the western genre later in the decade, perhaps given the licence to be more violent because of the precedent set by the Bond films.

Bond preparing to kill Dent like someone waiting for a potential sex partner to arrive. He takes great delight (watch Connery’s gleeful expressions) in arranging the furniture to make it look like he’s still entertaining Miss Taro. But his only date is with Dent. The camera lingers on Bond screwing on a silencer (one of the first to ever appear on film) bringing his pistol to its full length. After he has killed Dent, he removes this silencer with post-coital slowness, shortening the barrel so he can put the weapon back in its holster, ready for the next conquest.

It is perhaps significant that Dent falls down dead adjacent to the bed where Bond has just had sex with Miss Taro, the duplicitious Government House secretary secretly working for Dr. No. Regarding Miss Taro, Licence To Queer writer ‘0067’ says: “I have always found something quite trans about her. I think it's because she is getting ready. Trans women are always filmed getting ready. It's a stereotypical thing often used in articles, films, TV shows, but it's mostly whenever there is a documentary featuring a trans woman. They always have them getting ready, doing their hair, painting their nails, and of course makeup. It became a comical cliche, and kind of came to be used as a sign as to whether the filmmaker got it or not. If they used that then they're just making it for sensational purposes. Because, you know, trans women don't actually sit around doing that stuff all the time.”

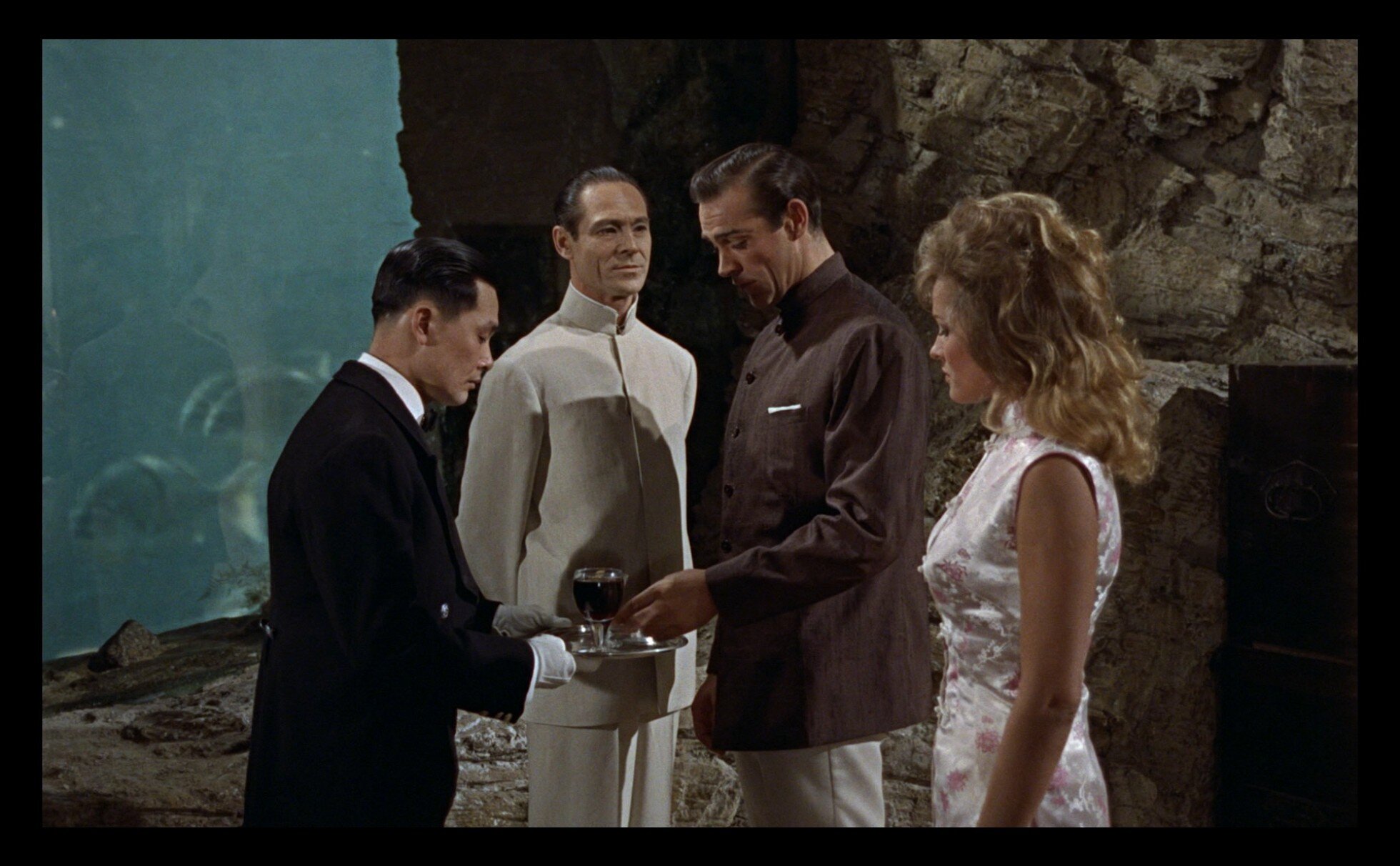

As soon as Bond falls into the clutches of Dr. No, the film’s tone changes to something approaching science-fiction. Norman Wanstall’s sound design and Ken Adam’s sets establish an Othered-otherworldliness so that, by the time we eventually meet the titular villain, we are prepared for almost anything.

Before Bond and Honey can meet Dr. No, they are stripped naked in a sequence invented for the film and designed to exploit one of the advantages film has over literature: it’s a predominantly visual medium. While the feeble pretext is that Bond and Honey are covered in radiation and need to be forcibly scrubbed clean, it’s really an excuse for us to gaze upon Connery and Andress. It begins with them both being sprayed all over, by Dr. No’s henchmen, with thick white foam - an obviously onanistic metaphor which I don’t think you need me to explain.

The chief villain’s first interaction with Bond is unique in the series: he peels back the bed sheet to get a good look at his adversary (although the power dynamic is echoed in Silva’s peeling away of Bond’s shirt while he’s strapped to a chair in Skyfall). Once again utilising the strengths of a visual medium, this first meeting (with Bond knocked unconscious) is something which is far more sexualised than it is in the novel. For a start, Connery is framed in the exact same way he was as when being attacked by the spider, in a similarly vulnerable position. The sexual aspect is greatly heightened by us only seeing Dr. No’s hands, which are concealed in shiny black gloves. Unexplained at this point in the film, the sight of his gloves might cause our minds to run in the direction of kink. And perhaps it’s only afterwards that the question forms: who removed Bond’s clothes? Before he was drugged, he was wearing a blue robe. But it’s clear that Bond has been relocated to the bed and is now somehow naked. Presumably, it was some of Dr. No’s willing underlings: but why did he request Bond to be stripped? In film time, we see Bond naked on two separate occasions in under ten minutes.

Upon waking, a fully clothed (but not for long) Bond finally gets to meet Dr. No. Slightly less of a racist stereotype than the Fu Manchu-like character of the novel, his principal physical characteristic is his metal hands, which he fashioned himself after a lab accident, the circumstances of which are undisclosed. Writing about the treatment of transformation specifically in science fiction, queer academic Antonio Fernando Cascais observes that physical metamorphoses correlate with a change in identity. Dr. No has compromised himself: he is no longer a ‘natural’ human specimen, certainly in comparison with Bond, whose able body is on full display, and will be again shortly as he is put through the wringer of Dr. No’s obstacle course, shedding garments as he goes.

Dr. No is not completely cut off from the natural world. He’s already tried to kill Bond with a spider. Indeed, there may be something more arachnid about him. In Fleming’s book, the chapter where Bond meets Dr. No is entitled Come Into My Parlour, an idiomatic phrase which is misquoted from a poem published in 1829 by English poet Mary Howitt. The poem tells the story of a spider charming a fly into becoming lunch, the moral being to see through flattery and attempts at seduction. And this scene really does set the template for the seduction scenes which have become a staple of the Bond series.

Animal metaphors and their obverse abound in this film. Bond derides Dr. No as a “minnow” pretending to be a “whale”. In retaliation, Dr. No labels Bond a “stupid policeman”, a representative of a fabricated human institution. Natural and unnatural is a binary opposition and one which is familiar to anyone who has been made to feel unnatural at some point in their lives, as many queer people have. Perhaps this is why science fiction appeals to queer people so much, a genre which (again, according to Cascais) “is occupied in overcoming notions of binary oppositions, between norm and deviation”.

While Bond is hardly ‘normal’ himself, he’s not as great a ‘deviant’ as Dr. No. One of the shadiest lines in all of the Bond films is Bond’s sardonic enquiry: “Tell me, does the toppling of American missiles really compensate for having no hands?” It’s more than a hint that Dr. No is missing a part of himself which many men - certainly Bond - would consider essential for defining themselves as men. Yes, we’re back to the castration complex yet again. Hands are a common symbol for male genitalia in Surrealist art, including works by Salvador Dali who is name-checked several times in Fleming’s Bond books.

Dr. No’s metal hands make him a symbolic eunuch who must ‘topple’ other men’s missiles in order to make them notice him. With its ever more blatant phallic-imagery, the James Bond series will do more than most movies to depict the psychological bases of Mutually Assured Destruction and the Space Race: a penis-measuring contest. And it all begins here, with Dr. No.

Ultimately, it’s Dr. No’s unnatural penis-substitute hands which are the death of him: superhumanly strong they may be but they lack the dexterity of natural human hands which would have saved him from sliding to his death. Deviant Dr. No is put back in his box in time for the final scene of reconciliation and romance between the two able-bodied characters.

Like many of the villains to come, Dr. No has no romantic or sexual interest in other people, making him a possible candidate for aromantic or asexual representation. Besides looking voyeuristically on at Bond while he sleeps, there are no signs that he’s interested in any part of Bond other than his brain (“I was curious to see what kind of a man you were.”), suggesting he could be identified as sapiosexual. On the other hand, perhaps his choice of home decor gives us an indication of what or who he’s attracted to. A prominently featured objet d’art is a Goya painting, a copy of a real life painting of the Duke of Wellington which had been stolen shortly before the film’s production (Ken Adam painted the film’s version over a weekend).

Goya himself directly correlated non-normative sexuality with disability. A sketch by Goya, completed in the early 19th Century, shows a deformed man with effeminate posture wearing a dress. Above there is a caption: El Maricon de Tia Gila. Translation: The Faggot, Auntie Gila. Goya’s intention was to show how queerness and disability were closely related.

Perhaps Goya’s own queerphobia was a consequence of loathing something he recognised in himself. Widely considered to have been the father of Modern Art, that’s not all Goya fathered. He had ‘around’ 20 children (presumably it was difficult to keep track after a dozen or so). A promiscuous lover of women, he would have given James Bond a run for his money. Perhaps this was a case of Don Juan Syndrome, where a man has sex with as many women as possible as a result of feeling insecurity about his masculinity, perhaps because he is also attracted to men. In 2005, art historian Natacha Seseña published a book Goya And The Women, in which she explored not just Goya’s women, but what was quite obviously a sexual relationship with his best male friend. The letters Goya sent his best mate Martin are certainly steamy, even by today’s standards. In one, the artist urges his friend to run away with him and another features detailed drawings of genitalia next to a suggestive sign off. Perhaps an early form of the modern invocation to ‘Send nudes’!

Dr. No’s decision to imprison Bond in a easily-escapable cell rather than kill him is a curious one. The subsequent escape has more than a whiff of sadism about it, with Connery being steadily stripped of his clothing (again!) while undergoing physical torments. In the novel, the scene is far more explicitly sadistic, with Dr. No telling Bond he has designed the obstacle course to push him to his physical limits before killing him. The book’s tortuous trial finishes with Bond being attacked by a giant squid, its tentacles probing parts of his body. Perhaps it wasn’t just budgetary constraints that prevented this from being replicated on screen but a realisation that there was something very queer going on in Fleming’s novel that might be unpalatable in a mainstream film. Some of the queerness does survive in the screen adaptation however.

Examine millennia of stories in the Western literary tradition - Theseus and the Minotaur, Beowulf, Dracula - and you will find something psychosexual going on whenever a hero enters a villain’s lair, which is usually a reflection of the villain in some way. The word ‘lair’ derives from the Old English word for ‘resting place’ or ‘bed’. When a hero enters a villain’s lair, they are quite literally entering their bedroom. Nowhere is this more true than in Bond films, and Dr. No in particular. Architect Dr. Harriet Harriss’s insights on this are worth quoting in full:

“Bond villain domains form a backdrop against which many common domestic anxieties are explored, particularly in relation to women’s confinement within the home. For example, the villain’s lair is typically isolated, thereby forcing intimacy between the villain and his mercurial and often reluctant girlfriends - invariably requiring Bond to engage in acts of rescue. As Dr No put it, “together, that is sovereignty. The world is too public. And how do I possess that power? Through privacy”. The desire to simultaneously achieve “togetherness” and “privacy” is of course a conundrum faced by most nuclear families and spawned the drive towards suburban isolation – against which teenagers, seemingly much like Bond – have attempted to rebel.”

Here’s what I take from this: upon entering a lair, the (usually male) villain is positioned as a romantic and/or sexual rival to Bond, who seeks to have the Girl settle down and live with him. Bond setting out to destroy the villain and his lair can be seen as analogous to an adolescent’s unwillingness to emulate his parents in settling down in suburbia. Perhaps this is why we have so many millennia of stories where heroes enter villain’s lairs: there’s something universal about rebelling against one’s parents. Specifically in relation to Bond, we will see this pattern repeated across many of the films to come.

Dr. No queers this convention further by putting obstacles in Bond’s path which are highly visually suggestive: the sphincter-like pipes which Bond forces himself through with great exertion are, quite literally, Dr. No’s back passages.

You go gurrrrrls

Right from the beginning, Bond’s girls are so fiercely independent that referring to them - possessively - as ‘Bond’s’ seems somewhat inappropriate.

As we established in Bond’s introduction (see above), Sylvia Trench is more masculine than he is in several vital ways.

A red dress can signify many things about the wearer. Fashion scholar Julia Brucculieri says: “the color red, like women themselves, contains multitudes. In some ways, it’s cute, but it can also be powerful, sexy, sensual and erotic. And, of course, it’s bold and beautiful.”

Trench’s dress certainly draws our attention as filmgoers. Scholarship by Llewella Chapman, the author of Fashioning James Bond, has revealed that the dress began life as a piece of fabric that was merely chosen for its colour. It was fashioned into a dress that was so loosely held together that it could only be shot from certain angles. It looks like it could fall off her at any moment, which is perhaps Trench’s intention. She’s more than a match for Bond with his sport sex-ready cocktail cuffs which shows he doesn’t have time for fiddling about with cuff links when he - or someone else - needs to take his shirt off in a hurry.

Like Bond, Trench isn’t afraid to integrate the masculine and feminine. When Bond discovers her playing golf in his apartment, she’s wearing one of his shirts, a pair of gold high heels and - we presume - nothing else.

Walt Odets (see above) observes that anxiety about gender sensibility as expressed through clothing is long-standing, citing the Biblical prohibition “A woman shall not wear a man’s garment, nor shall a man put on a woman’s cloak” (Deuteronomy 22:5). Try telling that to James Bond, who wears Tracy’s robe in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. And tell that to all of those Bond Girls who have worn his shirts over the years. What has become known as the ‘sexy shirt switch’ cinematic trope, where a woman wears a man’s shirt, has become a trope in part because of the Bond films, although it was starting to appear in films as early as the 1950s. According to media historian Moya Luckett, the image of a woman in a man’s shirt is appealing to men because it allows them to live a James Bond fantasy of a string of disposable women passing through their lives. Eunice Gayson as Trench helped to establish the trope, albeit with a queer twist. The trope is most commonly employed to denote that coitus has just taken place. Trench is wearing Bond’s shirt prior to sex, indicating that Bond may be excited at the prospect of a woman with some masculine qualities. And this is not an isolated incident; Bond being attracted to masculine-featured women will recur across this film and many of those to come, as well as being rooted in Fleming.

“I’m just looking”

According to Dr. No’s director, Terence Young, Sylvia Trench was supposed to be completely naked in the scene in Bond’s apartment. Young spends a sizeable proportion of the ‘banned’ laserdisc commentary from the early 1990s bemoaning what he couldn’t get away with in terms of female nudity - although to be fair, he doesn’t miss any opportunity to draw our attention to Connery’s muscles either. He’s an equal opportunities objectifier, as can be seen from what made it into the finished film.

I’m wary of stealing the Girls’ thunder here, but it’s worth noting quite how much we see of Connery and how much the camera treats him - in cinematic terms - like a girl. As Laura Mulvey famously alerted us to, a consequence of most films being made by straight men is that the camera lingers on women’s bodies, inviting the viewer to gaze on at them, turning them into sexual objects. Very infrequently do men get the same treatment. And when they do, they receive little in the way of critical attention. Toby Miller is one of the few academics to spend as much time on Bond’s body as the women’s:

“The process of bodily commodification through niche targeting has identified men’s bodies as objects of desire, and gay men and straight women as consumers, while there are even signs of lesbian desire as a target. Masculinity is no longer the exclusive province of men, either as spectators, consumers, or agents of power. And Bond was an unlikely harbinger of this trend.”

In Dr. No, everyone wants to take a longer look at Bond. It’s a classic cinematic trick to direct our gaze by having a character’s eyes follow another around a space, something that happens in every Bond film and some more than most. The receptionist of Bond’s Jamaica hotel tracks down his body as he turns away, inviting us to do the same.

Although it would take until 2006’s Casino Royale to truly balance the books, having Daniel Craig re-enact Ryder’s walk through the waves, the camera loves Connery in Dr. No and Young doesn’t shy away from finding the best angle to show off his star. Connery spends a significant amount of the screen time nearly naked - and we’re all here for it. Only a very insecure straight man would have a problem with admiring his form.

Anyway, back to the Girls…

“I promise I won’t steal your shells”

Just as our gaze was drawn to Bond by looking at others’ eyelines, we are first shown Honey Ryder ‘through’ Bond, although it’s another sense that forms our first impression of her: our hearing. It’s not Ursula Andress singing Underneath The Mango Tree but Diana Coupland, then wife of composer Monty Norman. The lyrics of the song establish Ryder as someone who is closer to nature and Bond (“mangos, bananas and tangerines…”) but no less of a sexual animal (“Me honey and me make boolooloop soon” - “boolooloop” being a euphemism for coitus). The full version of the song (not heard in the film but included on the soundtrack) is a romantic ballad which tells a predictable heternormative tale of marriage followed by raising children - nine of them.

Maybe it’s just me, but I think Honey Ryder might have other plans, at least in the interim; she has ambitions of being a call girl in Fleming’s novel, an idea Bond isn’t terribly keen on. Like with Sylvia Trench earlier in the film, the original plan was to have Honey appear wearing even less than a bikini. If they had reproduced her appearance exactly as it appears in the novel there would have been scandal. Even so, the idea of her being Botticelli’s Venus reaches the screen mostly intact, down to the shells she is clutching. Shells are a common symbol of female power because of their vaginal appearance, an analog for the symbol of male power omnipresent in Bond films: phallic-shaped guns.

Filmmaker Mark Cousins calls the scene a ‘dream sequence’ perhaps because of its abstract qualities. Or perhaps we’ve seen her picture somewhere before?

Fleming himself references Botticelli’s Venus to describe Honey. Specifically, she’s Venus “seen from behind”, which would require considerable imagination as Botticelli never gave us the rear view. Even more curious is Fleming describing Ryder’s behind as “almost as firm and rounded as a boy’s”, something his gay friend Noel Coward pretended to find shocking when he read the finished manuscript of Dr. No. Perhaps Fleming was aware that Botticelli himself was probably gay and combined aspects of male and female beauty in his mythical figures. The Renaissance painter was a good friend of another famous queer artist, Leonardo Da Vinci, who also incorporated androgny into his work. Perhaps this is what Fleming himself found appealing.

Venus (a.k.a. Aphrodite, in Greek mythology) is sometimes thought of as the personification of ‘softer’ femininity, balancing out the ‘harder’ war-bringer Mars. Like all mythological characters, various versions exist. In most Ancient texts, she plays a vital role in absorbing and tempering the male essence, uniting the extremes of male and female. The same is true for Dr. No with Honey Ryder.

Ryder is feminised by her association with nature in contrast with the comparatively masculine urbanite Bond. But like Mother Nature, Ryder exerts power over her natural world. Like Dr. No tries to do with Bond (via Dent), she has previously employed a spider - a female Black Widow no less - to destroy her enemy: the man who raped her. She also explains to Bond how a preying mantis eats her husband after making love. Note, the heteronormative assumption that even mantises get married. Is this a warning for Bond to take things slowly?

Ryder is given additional impetus for seeking to destroy the male power which controls Crab Key: Dr. No murdered her marine zoologist father. This is an addition to the film which does not appear in Fleming’s text. Strangely, although Ryder has less of a personal investment in the book, she has far more agency. She is the one who comes up with the idea of hiding from Dr. No’s patrolling guards by using the reeds as snorkels and rescues herself rather than wait for Bond to get around to it. And in the closing pages she orders Bond to strip naked and, when he objects, she boldly tells him to “Do as you’re told”. They’re the very last words of the book in fact. Can we imagine if such a scene had closed out the film and become the convention for the Bond film series that followed?

In the book and film, Ryder is not a demure, delicate flower. She is more like her shells, with their tough exteriors and concealed inner life. She only becomes truly vulnerable when she is approaching the dinner with Dr. No where she is relieved to find that Bond’s palms are sweaty too. He drops the macho facade and admits to her that he too is scared. Vulnerability is an aphrodisiac for this modern day Aphrodite.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

Maurice Binder’s title sequence, featuring both male and female dancers, is a riot of rainbow colours from sixteen years before Gilbert Baker accomplished a similarly brightly-hued feat of graphic design with his iconic gay rights flag.

There are a couple of Hot Bond Boys With Bit Parts in Dr. No, including two in the same scene: the Secret Service communications operator and the Foreman of Signals, whose cardigan has drawn comparisons with Ben Whishaw’s cutie Q. Perhaps they are standard issue in the Service?

The treacherous Mr Jones is also easy on the eye and earns additional kudos for having the most Camp line delivery in the whole film (and that’s saying something!). After biting down on a cyanide-filled cigarette he falls into Bond’s arms and seethes the line: “To hell with you.” While cyanide is hardly a laughing matter in real-life (see: Alan Turing), this line never fails to crack me up. Or is that just my warped sense of humour?

Hard as it is to imagine a Bond film without humour nowadays, it’s debatable whether Dr. No’s laughs were intended. Johanna Harwood recalled in 2019 (her interview with Robert Sellers), that it wasn’t until the first preview audience started laughing that anyone on the production knew they had a comedy on their hands. The script which she began and finished was more darkly psychological than the sardonic film we ended up with. In the early 90s, director Terence Young stated that he and Connery were 90% responsible for the comedy in Dr. No, which they improvised on set. He specifically cited the line “Make sure he doesn’t get away”, which Connery utters after driving up to Government House with the corpse of Mr Jones in the backseat.

Editor Peter Hunt says some of the humour came in the editing room, with lines overdubbed to make them funnier, sometimes by changing single words. Hunt himself claims credit for having the idea of the music Mickey Mousing along with Bond’s actions as he bashes the spider to death with his shoe.

Whatever the origin of the humour and whether it was supposed to be funny or not, Dr. No IS a very funny film. In her famous essay on Camp, Susan Sontag was of the view that: “The pure examples of Camp are unintentional; they are dead serious”. If not entirely pure Camp, Dr. No comes pretty close. Most of the funniest lines come from the mouth of Bond himself, who is far from dead serious, even when - especially when - death is on the cards. This is another element which makes Bond fit the stereotypical template of the gay man, who society expects to be ready with a one liner whatever the situation. Academic Rainer Emig says: “In the same way that black people have to live up to the racist stereotype that they all “got rhythm,” gay men constantly have to prove that they are capable of witty repartee.”

Queer verdict: 004 (out of 007)

Few films in cinema history have done as much as Dr. No to define what we think of as ‘masculine’. And yet, a closer inspection reveals that Bond is not so terribly manly after all. The devil is in the details, with the character and his world subtly - and not so subtly - calibrated to make us question our assumptions. We all bring to a film our own personal baggage and we all take different things away. But the DNA of Bond is undoubtedly queer. Although it could have turned out very differently had the filmmakers strayed further from Fleming’s book, they didn’t. Dr. No set the queer genetic blueprint for the others to follow.

Acknowledgements and further reading

The main idea that runs through this piece - that Bond integrates both masculine and feminine traits and this has implications for his sexuality - has been running around in my head for a very long time: probably not long after I saw my first Bond film as a child, although it’s taken three decades for my thoughts to coalesce into something coherent enough to be written down!

It makes some people upset when you challenge the gender binary of male/female. And I know people who totally get that gay people exist and are fine with us existing (well, that’s a relief!), although these same people may struggle to accept bisexuality is a thing. Some people are more open to seeing things in less binary ways. This is especially the case with gender. As soon as you bring up gender as being determined by anything other than what you have between your legs, some people get quite emotional. It takes more mental effort to prevent yourself thinking along binary lines. I’ve alluded to these contrasting attitudes in the piece itself and intentionally over-simplified at times to keep things focused on Bond. But like James Bond always returning, this is not something I will be leaving alone.

What that has influenced my thinking more than anything has been my reading of the works of Meg-John Barker and their collaborators, including Jules Scheele and Alex Iantaffi. Their non-binary perspectives have helped me to get my head around gender more effectively than anything I have read before. I still have more to learn and any misconceptions are my own. We’re all learning when it comes to gender!

As Meg-John and Alex say in their book Life Isn’t Binary (which I recommend to everyone):

“The gender binary is - if anything - even more deeply rooted in white western dominant culture than the sexuality binary, although they are inextricably linked. Being seen as a “real” man or woman is significantly defined by attraction and desirability to the “opposite” gender. And men and women who are attracted to the same gender are often stereotyped as being feminine men or masculine women.”

The deep-rootedness of the gender binary makes it challenging to unpick how gender works. I have given it a go through the prism of Dr. No. Let me know if I have got anything wrong.

For the more candid behind the scenes comments direct from the mouths of the creatives involved (including director Terence Young, editor Peter Hunt and production designer Ken Adam) I relied on the ‘banned’ laserdisc commentary of the film, available for download from 007 Dossier: https://www.the007dossier.com/2011/04/21/banned-james-bond-commentaries/

Thank you to Dr Llewella Chapman who I have been in dialogue with while writing this - in particular, thank you for sharing with me your lectures on costuming.

Thank you Hannah Whitty (@Hannah_Whitty) for very useful resources about disability in science fiction

Thank you as usual to Lotte (@backlotte) for her great insights.

Thanks to @MarcusPetaja for some lively back and forth about the meanings of cigars (and ongoing proof-reading support).

Author Charlie McNabb has created a bibliography of books, articles, films and TV shows about the experiences of people who are both disabled and queer.

For details of the men’s clothing, I have been heavily reliant on, as ever, From Tailors With Love and Bond Suits. Also to the staff of Turnbull & Asser on Jermyn Street, London, from where I purchased my blue Dr. No cocktail cuff shirt (several sizes smaller than Connery’s). The staff were very informative about their company’s connections with the film.

Thank you to Thunderballs for the visual inspiration.

References

Barker, M-J and Scheele, J (2019) Gender: A Graphic Guide London: Icon Books

Barker, M-J and Iantaffi, A (2019) Life Isn’t Binary: On Being Both, Beyond and In-Between London: Jessica Kingsley

BBC (1963) Desert Island Discs: Ian Fleming Originally broadcast 5th August 1963. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p009y5b3

BBC (2016) Acting Disabled Originally broadcast 29th December 2016 Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b085xr6j

Brooker, P and Spaiser, M (2021) From Tailors With Love: An Evolution of Menswear Through the Bond Films Albany: BearManor Media