Inside the Hurricane Room: learning to cope like James Bond

James Bond is not always the best role model for staying mentally healthy. When faced with battles in his own brain, he’s far likelier to slip into avoidance behaviours (martinis, girls, guns) than deal with them head on. Even so, within the pages of the original Fleming’s books, we find that Bond’s creator was ahead of his time: he was not only interested in the treatment of mental difficulties, but also armed 007 with a coping technique recommended by professionals today.

Imagine Bond setting off on his mission without receiving his briefing from M or his gadgets from Q. Uninformed and unarmed, he wouldn’t last very long. And yet, when it comes to mental health, this is how most of us go through life. Despite increasing social acceptance that our mental health is as important as our physical health, most of us are simply ill-equipped to battle with the mental health challenges we will face at some point or another.

One minute we can be cutting through life like a knife and then the next, without warning, we can find ourselves cut down by difficulties we don’t know how to deal with.

If we injure our bodies, we know what to do next, whether it’s to fix it ourselves or seek specialist support. If we’re suffering in the mind, the pathways are less clear. It still takes more courage to seek support for an unhealthy mind than it does for a sick body. And if support isn’t available, we can be left feeling powerless to help ourselves.

While the support of a specialist is always preferable, is it possible that James Bond could provide us with some insight into how to manage our mental health?

So many of us look to James Bond for lifestyle inspiration, why not also look for strategies that might, one day, save our lives?

“Spare me the Freud.” - Trevelyan to Bond, GoldenEye

There have been many attempts to get inside James Bond’s head, ranging from the scholarly to the scurrilous. A 2012 piece in The National even asked ‘Is James Bond in fact a psycho?’. But negligible serious attention has been paid to how James Bond deals with his mental health, except to point out the obvious: he drinks too much and has lots of casual sex to take his mind off his worries.

They can both be examples of what psychologists called ‘avoidance’ behaviours: the things we do instead of dealing with our issues, when to do so in that moment would be too painful.

Casual sex - when suitably protected, conducted safely, consensually and not performed with ex-Soviet fighter pilots with asphyxiating thighs - has never killed anybody.

That Bond drinks to excess is more concerning. A Christmas 2013 edition of the British Medical Journal posed the question ‘Were James Bond’s drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor?’. Although no doubt well-intentioned with tongue firmly-in-cheek, it doesn’t make for especially mirthful reading if you or someone you know has experienced the effects of habitual alcohol misuse firsthand.

But as much as snarky critical commentators love to bash poor James Bond over the head about his copious casual sex and drinking habits, the Bond series itself has put it far more elegantly. In GoldenEye, Alec Trevelyan attempts to unsettle Bond with this pithily accurate analysis:

“I might as well ask you if all those Vodka Martinis ever silence the screams of all the men you've killed... or if you find forgiveness in the arms of all those willing women for all the dead ones you failed to protect.”

Although it would take decades for the films to explicitly depict the mental toll taken on 007 by his murderous profession, Fleming’s Casino Royale begins with a reference to “soul erosion”. Throughout the 14 books, we find Bond repeatedly ruminating over bodies that were full of person until he killed or failed to protect them. An alcoholic beverage of some kind usually helps him avoid causing his distress to spiral. If not a Martini then a double bourbon in an airport departure lounge will do (see: the opening chapter of Goldfinger).

But this is hardly the end of Fleming’s interest in Bond’s coping strategies. If not intimately knowledgeable about mental illness, Ian Fleming was at least well acquainted with it. And - for his era - he was refreshingly open about it. In his final published interview, when asked by the interviewer if he thought you had to be neurotic (see note at the end about the meaning of this word) to be creative, Fleming agreed wholeheartedly: “I think that to be a creative writer or a creative anything else, you’ve got to me neurotic. I certainly am in many respects. I’m not really quite certain how, but I am. I’m rather melancholic and probably slightly maniacal as well. It’s rather an involved subject, and I’m afraid my interest in it does not go deeper than the realisation that the premise does apply to myself.”

Fleming had sufficient interest in mental health in general - if not specifically his own - to make a neurologist a recurring character in the Bond novels. Despite appearing in four of the novels (only two fewer than Felix Leiter), Sir James Molony often gets overlooked. Right from his first appearance, in Dr. No, the “famous neurologist” Sir James is established as the antithesis to M’s outdated attitudes towards mental health. When M phones him to ask whether he thinks Bond is fit for duty after almost dying on the previous mission, Sir James tells him 007 is ‘Physically he’s as fit as a fiddle’ but ‘There’s a lot of tension there’. Sir James implores M to ease up on Bond because even he has his limits. M isn’t very sympathetic; he thinks ‘Nowadays, softness was everywhere’. Representating a somewhat more progressive mindset, Sir James thinks to thimself “Was there any chance that he had got his message across into what he described to himself as M's thick skull?”

While Sir James bites his tongue in deference to M on this occasion, this isn’t the case in You Only Live Twice. By this point, Sir James is now “the greatest neurologist in England” and has been awarded the Nobel Prize. When M tells him it’s ‘incredible’ that 007 has been “going slowly to pieces” following the death of Tracy, Sir James gives M a piece of his mind:

"It's not in the least incredible. You either don't read my reports or you don't pay enough attention to them. I have said all along that the man is suffering from shock." Sir James Molony leant forward and pointed his cigar at M.'s chest. "You're a hard man, M. In your job you have to be. But there are some problems--the human ones, for instance--that you can't always solve with a rope's end.”

While M’s solutions are unenlightened for their time period, it has to be said that some of Sir James’s would hardly pass muster today. In You Only Live Twice, Sir James advocates the ‘cure or kill’ approach: sending Bond off on a near-suicide mission is the strategy Sir James and M decide upon shake him 007 out of his depression!

Is it depression though? We need to be careful when labelling any mental health difficulty. Having a diagnosis doesn’t always make mental health difficulties easier to treat - sometimes the opposite. The most persistent of Bond’s mental health difficulties throughout Fleming is accidie: a depression-like lethargy which sets in whenever he’s not on a mission. He lives for those occasions when M calls him into his office to give him a life or death assignment which, according to Fleming, only happens around twice a year. I wrote about this extensively in the Quantum of Solace queer re-view.

When Bond returns from his You Only Live Twice (mis)adventure he’s brainwashed and out for M’s blood. Sir James deprograms him with dangerously high doses of Electroconvulsive Therapy. Shocking, positively shocking! But I suppose when Fleming has Bond consuming dangerously high amounts of everything else (Bond in Casino Royale: ‘I hate small portions of anything’), why shouldn’t Bond also be given dangerously high doses of ECT?

It’s a fantasy. But even a fantasy bears some relation to the real world. And we shouldn’t write-off everything in relation to mental health that Fleming put between his pages.

“In the centre of Bond was a hurricane-room…”

To many people, James Bond is the epitome of imperturbability: he is perpetually calm and unruffled. With very few exceptions, this is the image of Bond that has been put forward on publicity material for decades. Even when angered (such as on the teaser poster for Licence to Kill, which cautioned us about being on his bad side), he is in control - and unperturbed by the things he can’t control. Bond, cinemagoers have been led to believe, is better practised at blowing things up than blowing things out of proportion.

The most avid readers of the Fleming books (perhaps because they are so brilliantly propelled along by exotic travel and arresting action) sometimes overlook how much of an insight we’re given into Bond’s brain: his thoughts, his feelings, his physical sensations. It’s difficult to put these on screen, even with a very clever script, ingenious soundtrack and a talented actor playing Bond.

In Skyfall, when Sévérine asks Bond how much he knows about fear, he replies ‘All there is’. It’s impossible for us to know the extent to whether he’s telling the truth or what is motivating him to make such a blasé statement. Is he trying to reassure her? It’s unlikely he’s being sincere. He’s probably just as fearful as she is; they are both putting on a good show.

In the books, we’re granted full access to Bond’s thoughts, feelings and physical sensations. The same could be said of any fictional character. But with Bond it means more. It means more because we associate Bond with physical action. But actions don’t happen in isolation.

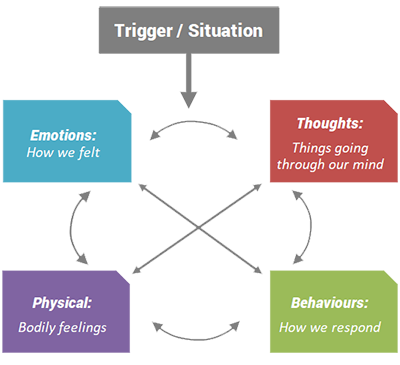

Understanding that our behaviours are connected with our thoughts, physical sensations and feelings is central to what we now call Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT for short). It’s now a well established intervention used in the treatment of anxiety, depression and other mental health difficulties. Fleming would not have been familiar with the term ‘CBT’ - it was not coined in his life time. However, the books are full of episodes where Bond tries to gain control of his body by changing the way he thinks and feels, or vice versa. In one extreme example, Bond attempts to literally thinking himself to death, willing himself to die before Goldfinger’s circular saw bisects him. The saw is upgraded to a laser in the finished film and Connery’s Bond talks himself out of the predicament rather than being saved by the villain’s sudden change of heart, but the reaction shots of Connery in the film sequence shows Bond trying to temper his anxious feelings so he can manipulate Auric into sparing his life.

CBT’s foundational ideas can be traced back to the Stoics, the Greek philosophers who taught that we should concern ourselves only with the things we have control over and learn to accept the things we cannot. The desired result? A feeling of calm. Nowadays, we use the term ‘stoic’ (without the capital ‘S’) to describe anyone who endures hardship without showing it. It’s frequently used to describe James Bond.

Of all the things Bond finds to cope with in the books, flying must be near the top of the list.

When his plane hits a tropical storm in Live and Let Die, Bond works himself into an excessively anxious state by thinking of all the reasons why they might fall out of the sky, convincing himself that his life will only be saved by his “stars” intervening on his behalf. To underscore how irrational Bond is being, Fleming closes this extraordinary passage, made up of rapid-fire staccato sentences which mirror Bond’s increasingly frantic mental state, by reminding us that the plane is “huge” and “strong”: the danger was in Bond’s head all along.

In Diamonds Are Forever, while still in the airport departure lounge, Bond’s first thought when he hears the flight dispatcher talking with Flight Control about the “Final Lounge” is a fatalistic one. There’s no turbulence this time, but during the flight there’s a revealing section where Bond projects his own anxieties about flying onto a fellow nervous passenger:

“Poor brute, thought Bond. He's terrified. He knows the plane is going to crash. … He is suffering the same fears he had as a small child--the fear of noise and the fear of falling.”

How would Bond have this insight if he hadn’t experienced these sensations himself?

By far the most prolonged passage giving us a window into Bond’s aerophobia appears in From Russia, With Love.

Having received his mission briefing, he has boarded a plane to Istanbul. Although this mission is particularly unusual and therefore could be a potential source of anxiety, his work-related ruminations do not cause him any undue distress. While his profession can cause him to feel depressed on occasion, it rarely causes him to worry unnecessarily. If there’s anything that Bond uses more than booze and sex as avoidance, it’s work!

Unfortunately for Bond, these quite routine mission-related ruminations are interrupted by something he has absolutely no control over: the plane flying through a thunderstorm. Over the next two paragraphs, Fleming grants us full access to Bond’s distress:

“Bond smelt the smell of danger. It is a real smell, something like the mixture of sweat and electricity you get in an amusement arcade. Again the lightning flung its hands across the windows. Crash! It felt as if they were the centre of the thunder clap. Suddenly the plane seemed incredibly small and frail. Thirteen passengers! Friday the Thirteenth! Bond thought of Loelia Ponsonby's words and his hands on the arms of his chair felt wet. How old is this plane, he wondered? How many flying hours has it done? Had the death-watch beetle of metal fatigue got into the wings? How much of their strength had it eaten away? Perhaps he wouldn't get to Istanbul after all. Perhaps a plummeting crash into the Gulf of Corinth was going to be the destiny he had been scanning philosophically only an hour before.”

Recalling the warning of his secretary not to travel on an unlucky date is what tips Bond over the edge and starts him catastrophising: fixating on the worst possible outcome and treating it as likely. To cope with his rising anxiety, Bond does the only thing within his control: he retreats inwards.

“In the centre of Bond was a hurricane-room, the kind of citadel found in old-fashioned houses in the tropics. These rooms are small, strongly built cells in the heart of the house, in the middle of the ground floor and sometimes dug down into its foundations. To this cell the owner and his family retire if the storm threatens to destroy the house, and they stay there until the danger is past. Bond went to his hurricane-room only when the situation was beyond his control and no other possible action could be taken. Now he retired to this citadel, closed his mind to the hell of noise and violent movement, and focused on a single stitch in the back of the seat in front of him, waiting with slackened nerves for whatever fate had decided for BEA Flight No 130.”

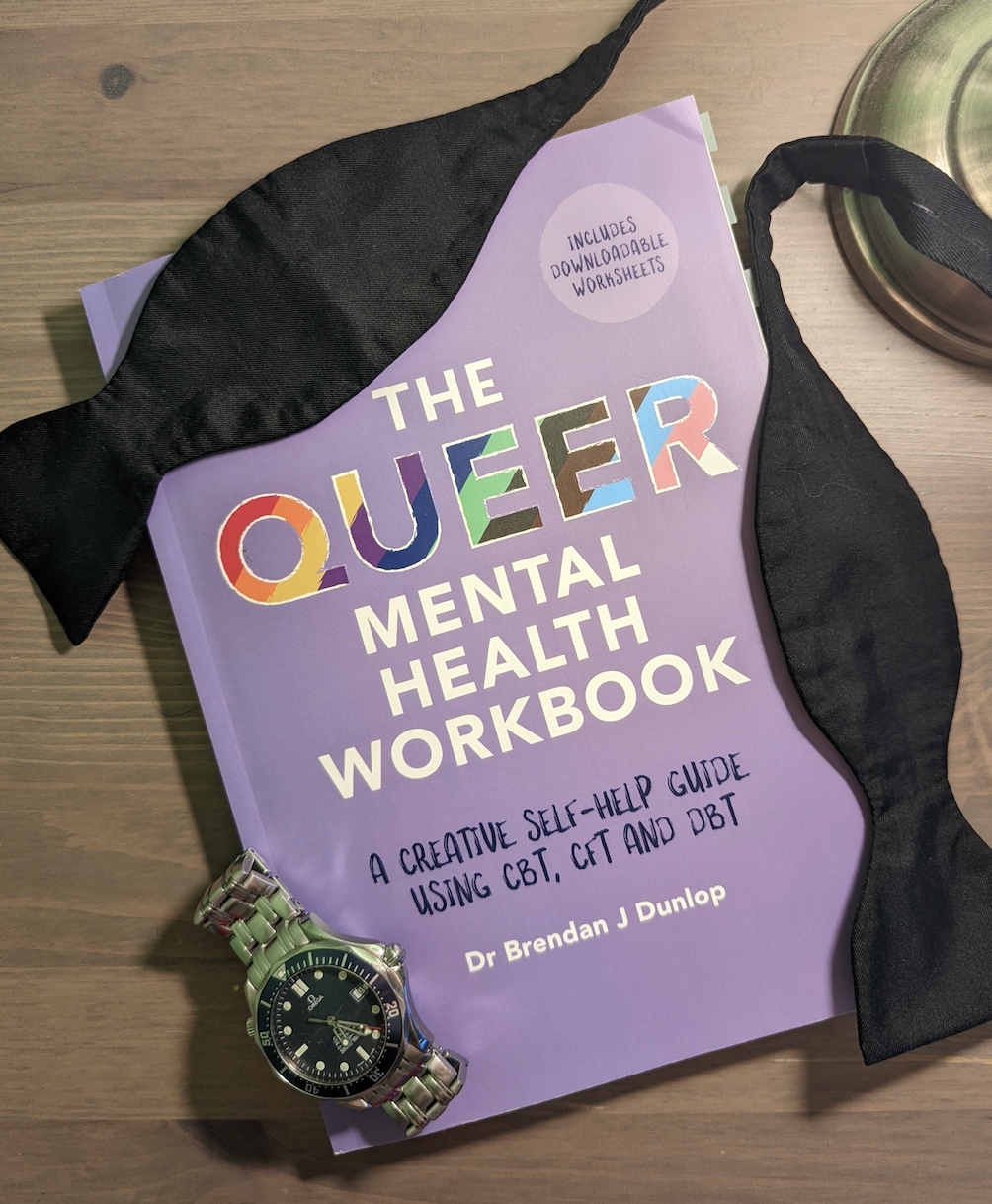

I discussed From Russia, With Love’s hurricane room episode with Dr Brendan J. Dunlop, a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapist and author of The Queer Mental Health Workbook. Dr Dunlop told me:

“This is certainly a CBT technique. It sounds like this is a ‘safe place’ that Bond retreats to when anxious, and folks in CBT are often encouraged to think of their own ‘safe place’ to help when things feel difficult for them to manage. In the feeling anxious chapter of [my] book I give a couple of examples of these ‘safe place’ scripts that folks can read when feeling anxious, and encourage people to create their own (full of as many senses as you like).”

Bond has written his own script, locating his safe space somewhere he feels at home: in the tropics, a place where Bond feels safe almost as much as his creator did. Remember that Fleming makes Bond an outsider in his home country, stating in Moonraker:

“Bond knew that there was something alien and un-English about himself. He knew that he was a difficult man to cover up. Particularly in England. He shrugged his shoulders. Abroad was what mattered.”

Fleming never tells us where Bond learned this CBT technique. But by Kim Sherwood’s 2022 novel Double or Nothing, the strategy has become standard-issue to all Double-O agents, or at least those trained by James Bond. In Chapter 2 of that novel, 009 - Sid Bashir is physically overpowered by the villain. Unable to move, Bashir does what Bond would do:

“Remember your training. Remember Bond’s words. At the heart of every agent is a hurricane room: in the tropics, the room a house kept empty at its centre so that when a storm begins to shake the skies, the family can retreat to this citadel without fear of flying chairs or the shrapnel of smashed crockery. … You retreat there when a situation is beyond your control… and wait for your nerves to come back. They’ll come back to you, and then you’ll stick your thumb into this man’s eye.”

There’s another passage in later Bond novel which is interesting to compare with From Russia, With Love’s hurricane room. This time, we experience danger not from the perspective of Bond, with all of his training, but a civilian. Instead of retreating to a safe space, Vivienne Michel finds herself unable to escape from the here and now:

“I suddenly realised that I had forgotten all about time. I looked at my watch. It was two o'clock. So it was only five hours since all this had begun! It could have been weeks. My former life seemed almost years away. Even last evening, when I had sat and thought about that life, was difficult to remember. Everything had suddenly been erased. Fear and pain and danger had taken over. It was like being in a shipwreck, an aeroplane- or a train-crash, an earthquake or a hurricane. When these things happen to you, it must be just the same. The black wings of emergency blot out the sky and there is no past and no future. You live through each minute, survive each second, as though it is your last. There is no other time, no other place, but now and here.”

Note the comparison with being in an aeroplane and a hurricane. The difference here is that Viv hasn’t been trained to use a hurricane room like Bond has. Fleming’s description precisely details what happens when we experience a true life-threatening emergency: our brains ‘blot out’ anything which isn’t going to help us navigate the here and now.

We should not take From Russia, With Love’s hurricane room episode by itself as evidence that Bond is a paragon of positive mental health. It’s true that, in this novel, all of his fearful feelings have evaporated by the time he lands in Istanbul… although it would be more accurate to say they have been drowned:

“An excellent dinner, with two dry Martinis and a half-bottle of Calvet claret put Bond's reservations about flying on Friday the thirteenth, and his worries about his assignment, out of his mind and substituted a mood of pleased anticipation.”

But he deserves kudos for not immediately reaching for the booze to get him through. He takes some personal responsibility for his mental difficulty. And who among us can say better than that?

A note on language around mental health

Throughout this piece I have attempted to avoid using language which reinforces the negative stigma around mental health, e.g. I have used mental difficulties rather than mental problems or mental illness. We all have mental health and we will all face difficulties. ‘Difficulties’, to me at least, suggests there will always be hope in overcoming them.

The word neurosis has been discontinued in some, but not all, medical circles, perhaps because of the negative connotations of the word due to the social stigma attached to mental illness. It was a Scottish doctor who first wrote down the word ‘neurosis’, in 1769. The World Health Organisation no longer use it and some parts of the NHS here in the UK discourage use of the term. The NHS website for Wales, for instance, points out that “'Neuroses’ are now more often called ‘common mental health problems’”. However, other parts of NHS website still use the term neurotic to disambiguate from mental health conditions which fall under the heading of psychotic, such as having hallucinations.

There are isolated occasions in Fleming where Bond experiences hallucinations. For instance, when regaining consciousness following a horrifying beating in Diamonds Are Forever, he believes himself to be back on a previous mission, Live and Let Die. Instead of succeeding on his night time swim to Mr Big’s lair, he never made it: Bond finds himself drowning to death in a nightmarish recreation, his wetsuit crushing him, the currents and the sea creatures dragging him down to the depths. But Bond’s hallucinations are usually short-lived. The only prolonged period of psychosis is his brainwashing by SMERSH occurs between You Only Live Twice and The Man With The Golden Gun.

Check out my in-depth discussion with Dr. Brendan J. Dunlop about Bond’s mental health (also available as a podcast):

The ‘On Our Minds Only?’ features Bond fans exploring many aspects of mental health and relating them to our favourite fictional character.