Agents provocateur: Bonding with the boys in blue

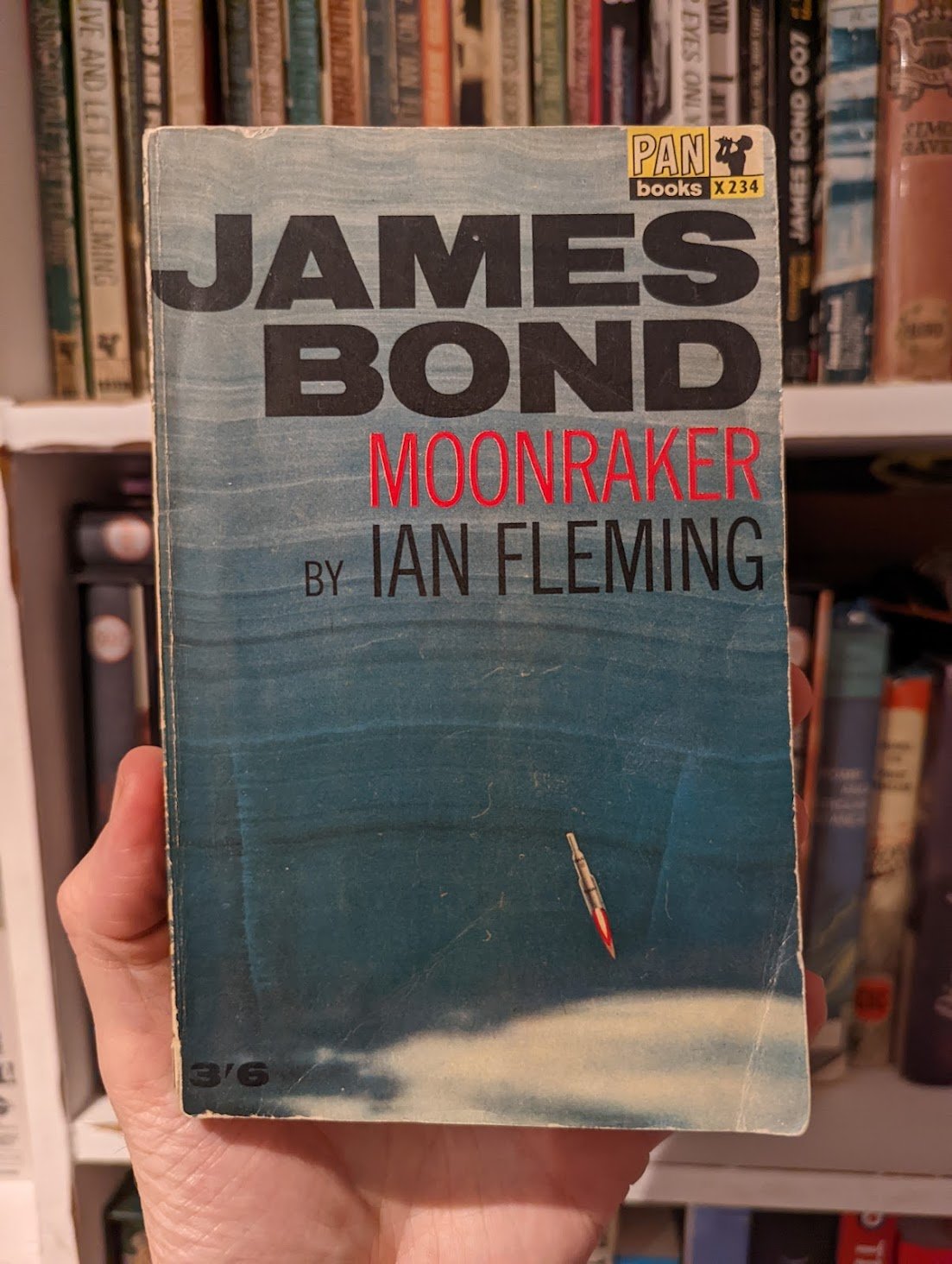

In 1955’s Moonraker, Bond gets mixed up in police business at a time when it was ill-advised for gay men to do so.

Although Dr. No might think otherwise, Bond is not “just a stupid policeman”. And yet, one of Fleming’s best books - Moonraker - finds him effectively on loan to the Special Branch of the Metropolitan Police. His mission: investigate a suspicious shooting. That he ends up, by the end of the novel, saving London from nuclear annihilation is entirely serendipitous.

Before heading off on his mission on home turf, he heads across London to Special Branch HQ to pick up some some intel. While awaiting his allotted meeting time with Ronnie Vallance, the Assistant Commissioner, he spends an agonising few minutes in the waiting room, desperately hoping no one mistakes him for a criminal, police informer or - perhaps worst of all, a parent of a gay child.

When I first read this passage as a teenager I assumed the ‘crime’ that led to gay people being arrested at this time would have been a sex act of some kind. I was aware that sex between men had still been illegal in my home country less than a generation before I was born.

It wasn’t until fairly recently that I came to realise that Fleming could be writing about several other ‘gay crimes’, some of which continued to be illegal into the 21st Century.

The 1967 Sexual Offences Act which legalised homosexual acts only did so partially. There were several caveats: the sex acts had to be conducted in private, between two men (no more) and the men had to be 21 or over (it would take until 2000 for the age of consent to be reduced to 16, as it had been for straight people since 1885).

In an 2017 article intended to shatter the ‘myth’ that the ‘67 Act did indeed decriminalise homosexuality, Stonewall co-founder Peter Tatchell summarised the situation:

“Centuries-old anti-gay laws remained on the statute book long after 1967 as “unnatural offences”. The two main gay crimes continued to be anal sex, known in law as buggery; and gross indecency, which was any sexual contact between men including mere touching and kissing. There was also the offence of procuring – the inviting or facilitating of gay sex. The law against soliciting and importuning criminalised men chatting up men or loitering in public places with homosexual intent, even if no sexual act took place. Men were convicted under this law, before and after 1967, for merely smiling and winking at other men in the street.”

Could it really have been as bad as Tatchell was making out?

My curiosity piqued, I took at peek through Hansard, the UK’s official report of all parliamentary debates. One in particular caught my eye, in part because it was from 1956, the year Moonraker appeared in paperback. Or at least, I thought it was from 1956. I had misread it: The debate was about amending the Sexual Offences Act of 1956, the one which stated that crimes like soliciting (chatting up another man) were an offence. But the debate itself had happened in 1984.

I couldn’t quite believe it had happened during my lifetime.

In the debate of 29th October 1984, the Labour MP (and Holocaust survivor) Alfred Dubs passionately articulated his reasons for amending the 1956 Act, asking that the law be changed so it was only possible to arrest someone for soliciting “when the offence is alleged to have been committed against someone other than a police officer”.

Why was he of the view that a change needed to be urgently made?

Dubs elaborated, and he didn't mince his words:

“To put it bluntly, police officers have been acting as agents provocateurs. Not for nothing are the police described as "Our boys in blue jeans." Matters are serious if police officers not only spy on what happens in public lavatories, but go into homosexual clubs, dressed like members of those clubs, with the sole aim of entrapping people into doing something that leads to a criminal charge.

…

“Those in the homosexual community believe that the police are conducting a vendetta against them. The many incidents that have been made public provide adequate justification for the widespread support of that view.

…

“I wish that the police would say bluntly, "We do not intend to go into the business of entrapment. We intend to take action only when there are victims."“

Britain wasn’t the only country where it was common practice for Police to send their young, attractive officers (wearing tight jeans and t-shirts) into gay spaces to entrap them.

George Chauncey, professor of history at Columbia University and the author of Gay New York has discovered than tens of thousands of gay men were arrested for cruising in the 45 years before 1969’s Stonewall, something he claims many have forgotten about. Chauncey explains the possible consequences of being a victim of such Police entrapment:

“While the arrests themselves left some men in tears and others furious, almost every man taken into custody feared the possible extralegal consequences more than the legal process itself. Above all, these men feared that their families or their employers would learn they were gay if word of their arrest reached them.”

Alarmingly, gay entrapment by discriminatory police forces still happens in some parts of the USA and in many other countries around the world.

The 2021 film Operation Hyacinth shone a light on the murky behaviour of the Polish Police at a time when the same practices were being debated in Britain. Between 1985 and 1987 they repeatedly raided gay spaces, including popular gay cruising spots such as public toilets. Their raids resulted in the registration of more than 11,000 gay people. If the history of the 20th Century has taught us anything it’s that making a database of people belonging to groups considered ‘undesirable’ by those in power rarely has a happy outcome.

Thousands of innocent lives were destroyed by these pernicious police practices, both abroad and at home. But according to some in Britain, the police were just doing what the public expected on them.

In the same 1984 House of Commons debate in which Alfred Dubs lambasted our “Our boys in blue jeans”, Conservative MP Eldon Griffiths (who was the son of a police sergeant and was the voice of the Police Federation in parliament) considered it his public duty to speak on behalf of parents, who were allegedly concerned:

“No police officer regards the duty described by the hon. Member for Battersea (Mr. Dubs) with anything other than distaste. The police want no part of this peculiarly nasty business. But they have to respond to pressures from the public. One of the principal reasons why police officers sometimes keep watch on public lavatories is that the parents of local children become alarmed about what they believe may be happening. Sometimes children are molested. When that happens, the fears and anxieties of parents are great.

“When complaints are made the police have no choice. They must do what they can to try to prevent molestation. I do not suggest that the natural action of homosexual males is to molest children. There is a distinction. Unfortunately, the public do not take as enlightened a view as the hon. Member for Battersea. Sometimes real fears and anxieties are transmitted to the police station. The police are expected by parents to do something about them.”

The 1980s saw a heating up of the moral panic around gay people, the flames being fanned by a mostly-willing mainstream media. Similarly facile ‘fears and anxieties’ are being expressed about trans people at the present time.

The good news with moral panics is they burn themselves out relatively quickly. But that doesn’t mean they don’t leave a smouldering mess behind. In some parts of Britain, police persecution of gay men continued into the mid-1990s. Soliciting in the sense of gay men chatting up other gay men remained illegal until 2003! That means that the passage in 1955’s Moonraker which has Bond anxiously twiddling his thumbs for fear that someone might mistake his purpose for being in the waiting room, a scene which might feel almost quaint to us today, could have appeared in any Bond novel - or indeed any work of fiction - until the year I finished university.

It would take until today - the day I am writing this - 4th January 2022 to make pardonable all convictions for victimless ‘crimes’ between consenting gay men.

The law may have changed but how much has changed within the culture of the police itself?

A 2006 report on homophobia within the police service for the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies concluded that while there had been progress there was still a long way to go because of a lack of consistency across police forces in England & Wales.

In December 2021, the Metropolitan Police force was accused of being “institutionally homophobic” for its handling of a “disturbingly incompetent investigation” into a serial killer preying on gay men. The Met may be headed by an openly gay person (Dame Cressida Dick) but how much has really changed?

I can only speak with any confidence from my personal experience with my local police force, West Midlands Police. Every time I have been a victim of hate crime, they have dealt with it swiftly and supportively. Personally, I cannot imagine their officers engaging in discriminatory behaviour of the kind that was endemic as recently as the decade of my birth.

This may be small consolation for any gay men who had their lives ruined by police entrapment but is it a sign of genuine transformational change within the institution which is supposed to keep us safe?